‘I just couldn’t give up.’ Shellfish producer France Haliotis solves abalone farming riddles like selective breeding, helper species and algae cultivation

Grit, determination and hard work can make the difference between survival and success in the shellfish aquaculture world. European abalone (Haliotis tuberculata) producer France Haliotis, against all odds, has just celebrated 20 years in operation. But the journey has been anything but smooth.

“Ten years ago, it was a different story,” Sylvain Huchette, CEO of the shellfish producer in Finistère in northwest France, told the Advocate.

Back then, Huchette was struggling to harvest enough wild seaweed to feed his abalone, housed in cages in the local bay. Storms had wreaked havoc on the production system, and market competition from cheaper wild abalone was making sales an uphill climb. Despite his determination to work in harmony with the ecosystem, it seemed like nature was winning – until a series of innovations turned the tide, leading to a flourishing and sustainable abalone farm.

An uphill battle

The challenges faced by France Haliotis are not unique. Globally, there are approximately 56 different species of abalone and 18 additional sub-species belonging to the Haliotidae family. The largest is the red or Pacific abalone, Haliotis rufescens. Many species are endangered and are CITES listed due to overfishing, which is a particular problem in South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

Historically, abalone were fished, but Japan and China began to farm the species in the late 1950s and early 1960s, to meet demand. By 1970, fishery production was around 20,000 metric tons (MT) with 50 MT produced via aquaculture. In 2020/21, the balance had reversed, with 4,510 MT fished and 243,506 MT farmed.

Today, China and Korea are the largest producers of abalone, with other major producers including Taiwan and Japan. However, illegal poaching remains a significant issue, particularly in South Africa, where around 3,000 MT of the abalone Haliotis midae is poached each year, mostly destined for the Asian market through Hong Kong, where they fetch hundreds of dollars per kilogram. A June 2024 report by TRAFFIC Southern Africa highlighted the challenges of controlling this illegal trade.

“Abalone fisheries have all but collapsed in South Africa, with control of wild-caught abalone in the hands of ruthless criminal syndicates,” according to the authors.

TRAFFIC’s investigations in South Africa found adverts on major online retailers that seemingly lacked the required documentation for the species for sale. They concluded that a combination of poor fisheries management, online anonymity and lax monitoring of online adverts is facilitating this illegal trade.

Despite these global challenges, France Haliotis found a way to navigate these turbulent waters and carve out a niche for itself in the European market.

Turning the tide

Today, the abalone are flourishing thanks to a number of crucial advancements: a selective breeding program, its own seaweed-growing operation, an upgrade to its production gear, and perhaps most importantly, the growth in popularity of farmed abalone in high-end restaurants across Europe. Achieving Ecocert organic status for both abalone and seaweed has also helped.

And it’s not just shellfish – France Haliotis has expanded into land-based sea lettuce (Ulva spp) farming using local species, where demand is beginning to outstrip supply. Huchette, who has always been passionate about environmental conservation and fascinated by the sea, has managed to align his career with these interests. Despite the hard knocks from production cycles, he admits, “I couldn’t just give up!”

A winning combination

France Haliotis is dedicated to both production and scientific research, offering valuable opportunities for students and welcoming hundreds of visitors to its hatchery each year. However, the company’s independence from wild abalone seedstock has been the most critical factor in its upward trajectory.

“When we started out, we used abalone from local wild populations to breed from, but the introduction of a selective family breeding program has enabled us to produce a faster-growing, higher-quality animal,” Huchette said. “We finally nailed the breeding cycle around six years ago and are now working with the F2 generation. Production is reliable and we have single-figure mortalities.”

Broodstock are spawned in June in the shoreside hatchery, where water is maintained at a constant temperature between 15 to 16 degrees Celsius (60 degrees-F). Solar panels on the roof provide much of the energy requirement.

The larvae graze on algae, grown on thin plastic sheets, from their fourth day. Once they have settled onto a sheet, the tiny animals are moved to an outdoor nursery, through which a constant supply of algae-enriched seawater flows.

The abalone are transferred to cages when they are six months old and moved out to sea. The farm has 200 cages, which sit on the seabed, attached to subsurface longlines. Once per month for adults and twice per month for juveniles, the cages are filled with freshly harvested seaweed, on which the animals graze.

“At any one time we have upwards of one million animals at sea, and it takes between 10 and 15 kg (22 to 33 lbs) of seaweed to make one kilogram of abalone,” Huchette said.

The animals’ favorite food is Saccharina latissima, a seaweed that is now grown on 2 to 3 km (1 to 2 miles) of longlines strung out in the bay, removing the need to work the tides to harvest the wild supply.

“We use the hatchery in the winter months to spawn seaweed and the summer months for the abalone, enabling us to make best use of our limited space,” Huchette said.

When ready for harvest, which takes around 3.5 years, the abalone are taken ashore, graded for size, and placed in holding tanks. Careful handling minimizes the animals’ stress.

“We sell abalone to the trade and through our online shop from 6 cm upwards,” he said. “Our farmed abalone are sold younger and smaller than wild abalone, and are consistent in terms of size, texture and quality.”

The abalone are packed into insulated containers, sent by 24-hour courier, and guaranteed to arrive alive. Vacuum packed abalone, abalone preserves and rillettes are also available.

New frontiers

France Haliotis has collaborated in numerous academic projects over the years, seeking to improve scientific understanding of genetics, mortalities, feeding and behavior. Two recent projects include a national stock enhancement and reseeding program for European abalone, and an investigation into the benefits of growing sea cucumbers in abalone cages.

“The sea cucumbers kept the cages clean and grew really well. We are now investigating market opportunities to allow us to add this species to our production cycle,” Huchette said.

Sea lettuce (Ulva spp.) production was started in conjunction with a South African partner, in six shallow 200-cubic-meter tanks. The tanks are seeded with fresh macroalgae culture, and a paddle system is used to keep the seawater and seaweed circulated constantly. The movement ensures that the delicate plants remain in constant movement to guarantee their growth, and also enables the entire water column to be used for cultivation.

Once per month, between April and November, the seaweed is filtered out through a harvest channel, then sold fresh or dried.

“We are developing a strong market for branded organic dried sea lettuce flakes, which make excellent seasoning,” Huchette said.

While the company’s success highlights the potential for aquaculture to offer solutions to some of the industry’s most pressing issues, it also underscores the complexities and difficulties that come with maintaining a balance between production demands and environmental stewardship. As global pressures on abalone species continue, France Haliotis’ experience could provide insights into opportunities and challenges faced by producers in this highly competitive sector.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Nicki Holmyard

Nicki Holmyard has written about the seafood industry for longer than she cares to remember! A committed pescetarian, she is also a partner in the UK’s first fully offshore rope-grown mussel farm.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Aquaculture Exchange: George S. Lockwood

With his book, “Aquaculture: Will it Rise to Its Potential to Feed the World?” hot off the presses, the pioneer abalone farmer vents on U.S. aquaculture regulations but remains deeply optimistic about fish farming.

Responsibility

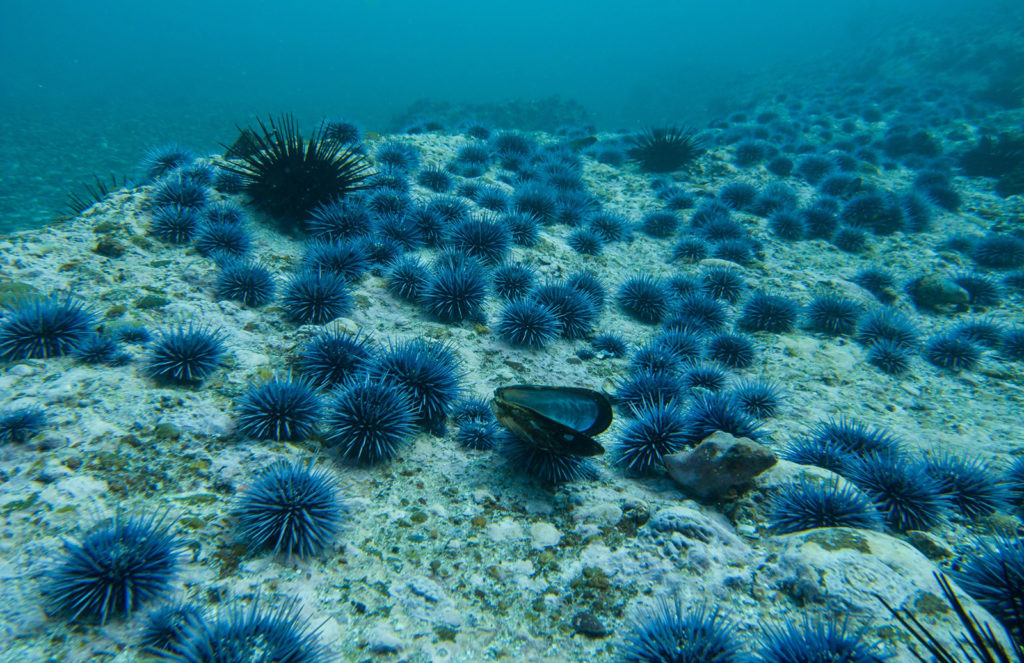

Can ranching ‘zombie urchins’ boost uni, save kelp forests?

With Norwegian knowledge and a partnership with Mitsubishi, Urchinomics aims to turn worthless empty urchins into valuable seafood while restoring kelp forests and creating jobs.

Health & Welfare

Integrated systems incorporate seaweed in South African abalone culture

South African abalone culture is growing and many of the land-based tank production systems use wild-harvested kelp to feed the animals.

Innovation & Investment

Artemia, the ‘magic powder’ fueling a multi-billion-dollar industry

Artemia, microscopic brine shrimp used as feed in hatcheries, are the unsung heroes of aquaculture. Experts say artemia is still inspiring innovation more than 50 years after initial commercialization. These creatures are much more than Sea-Monkeys.