West Virginia University establishes five-step process

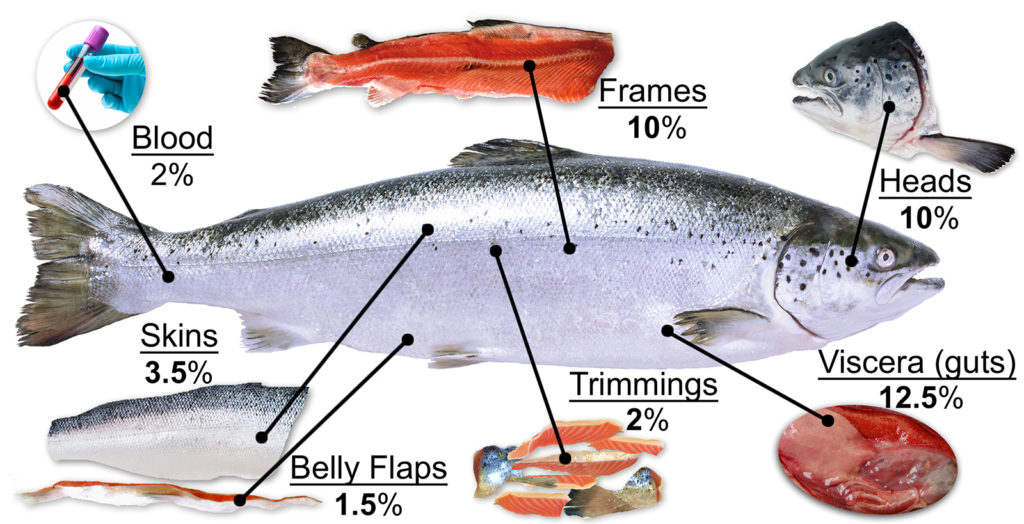

For the past two decades, the amount of byproducts generated from the processing of aquacultured fish has paralleled the immense growth in global aquaculture production. Filleting fish requires the removal of bones, skins, fins, and heads. Regardless of the species, industrial filleting generates significant amounts of these bypproducts.

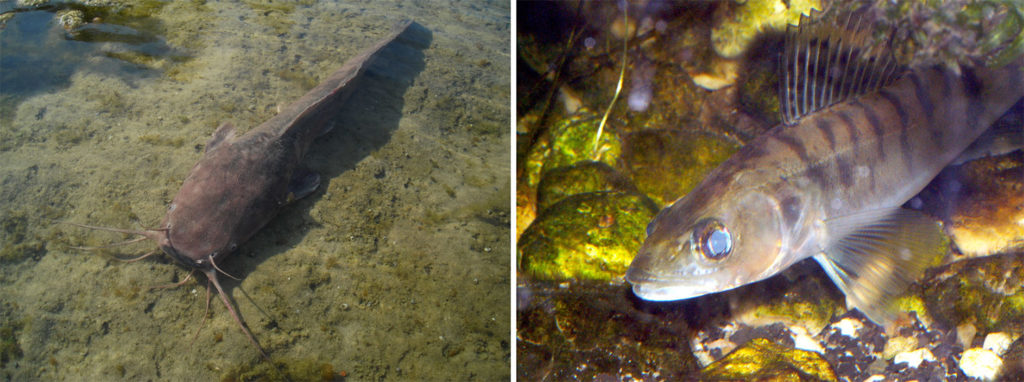

The mechanical filleting of 45 kg of trout yields approximately 18 kg of fillets and 27 kg of byproducts that contain about 9 kg of meat and 2 kg of fish oils (lipids). Mechanical filleting of 45 kg of tilapia yields about 14 kg of fillets and 32 kg of byproducts, resulting in even higher amounts of fish meat and oil being disposed of on a per-fish basis.

Disposal issues

The byproducts can be reduced to animal feed, but are often disposed of in land fills. The fish byproducts can not be fully utilized by the rendering industry due to the fishy odor caused by the auto-oxidation of the fish oil they contain.

The odor is transferred to the meat of the animals fed excessive amounts of fishmeal, resulting in lower meat quality, and thus, limited consumer acceptance. In addition, fish processors incur expenditures associated with the removal of processing byproducts from their facilities. The byproducts also place a significant biological burden on the environment.

Recovery technology

The development of protein and lipid recovery technology for the filleting byproducts is offers multiple advantages. As a new industry, it can generate new revenue and employment. The technology can more responsibly utilize available resources for human food and reduce the environmental stresses associated with the disposal of processing byproducts. It can also lower prices and expand the variety of nutritious aquatic food products.

Recovery process

West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia, USA, has developed both batch and continuous operation for protein and lipid recovery that efficiently recovers muscle proteins and lipids from fish-processing byproducts. The batch operation requires repetitive cycles of loading byproducts, processing, and unloading the recovered proteins and lipids. In contrast, the continuous operation mode allows continuous byproduct feeding, processing, and harvest.

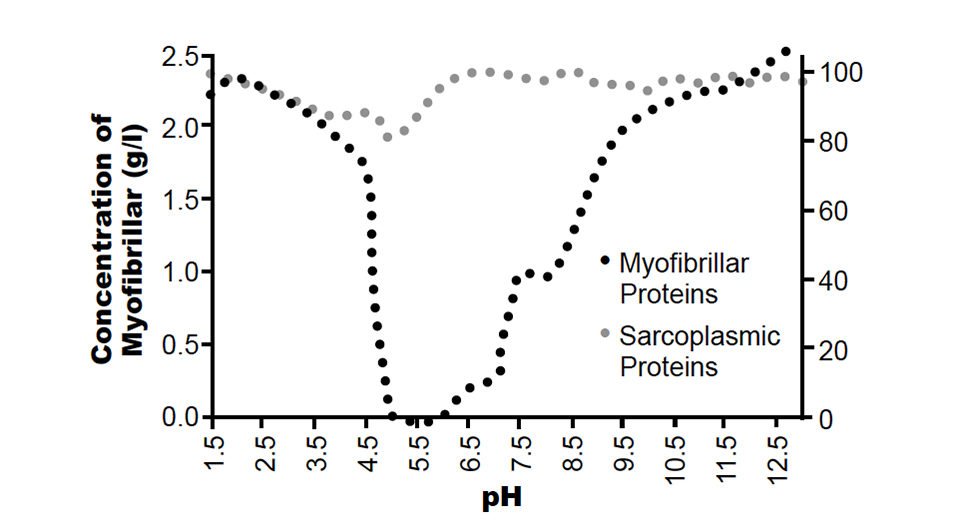

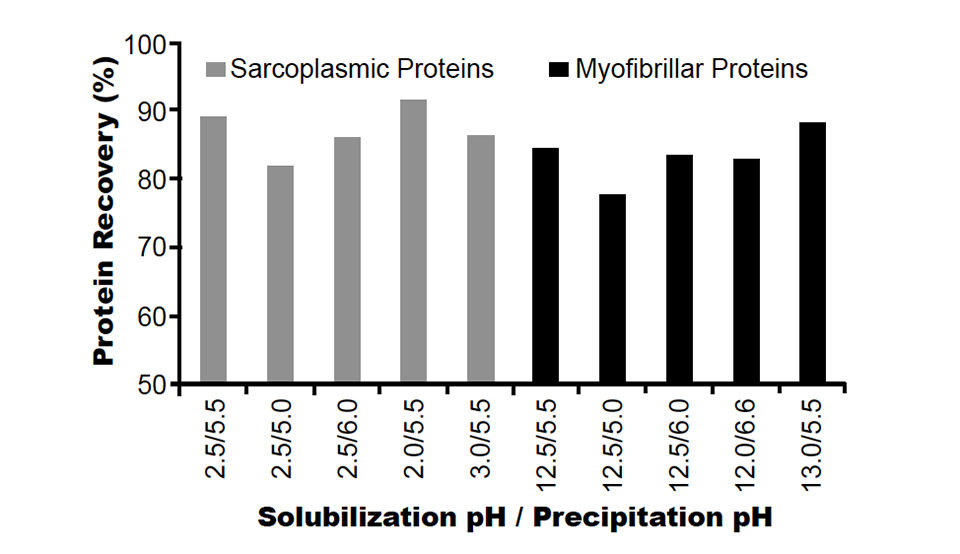

The recovery technology is based on isoelectric solubilization and precipitation of muscle proteins. The proteins are solubilized at either acidic (2.0 to 3.0) or basic (12.0 to 13.0) pH (Fig. 1), followed by removal of the insoluble fish oil and proteins, bones, skin, and fins, with subsequent protein precipitation at 5.5 pH and separation from water.

The muscle proteins recovered from trout retain their gelation, which is critical in the development of restructured, value-added food products. The omega-3 fatty acids included in the lipids recovered from trout do not undergo degradation due to the pH treatment during protein and lipid recovery.

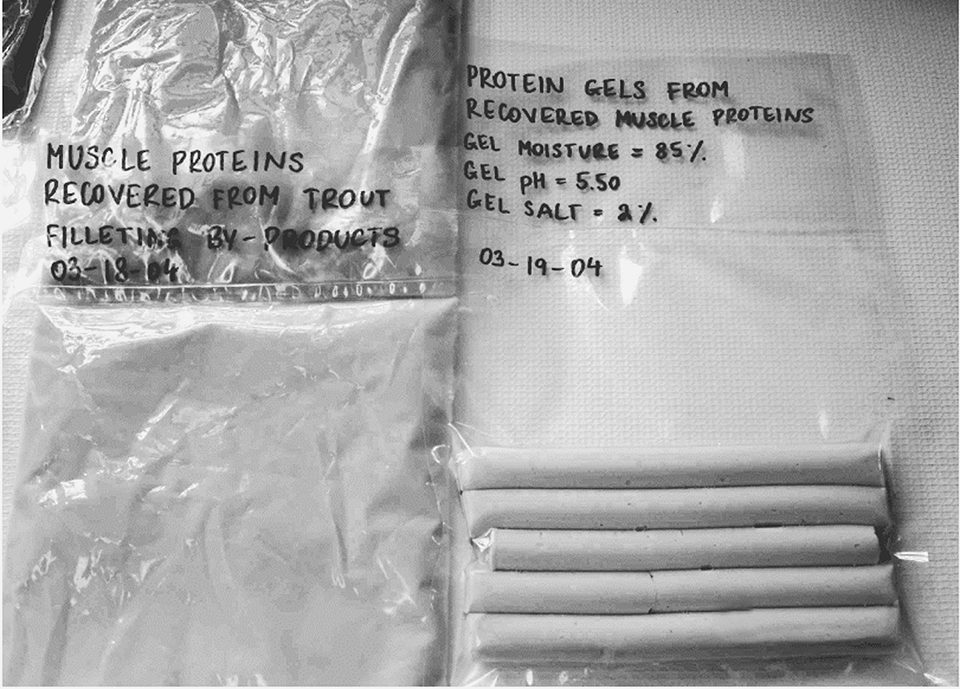

Protein gels from the recovered proteins have also been developed. The gels mimic restructured value-added foods and allow determination of texture and color properties, which are the two most important quality attributes for these foods.

Current developments

Batch mode

Experiments at West Virginia University established the five steps necessary to recover muscle protein and lipids from processing byproducts in a batch mode: homogenization; a pH shift that results in protein solubilization; first separation by centrifugation that separates bones, skin, and insoluble proteins from water-soluble muscle proteins and fish lipids; a second pH shift for the recovered muscle proteins that results in isoelectric precipitation of muscle proteins; and second centrifugation that separates the precipitated muscle proteins from water. The water separated in this step is protein-free and clear, and therefore can be recycled in the process.

Continuous mode

Based on the batch mode, protein and lipid recovery can be accomplished in a continuous mode using the same basic steps. The initial homogenization of the fish byproducts with water is accomplished using a continuous meat homogenizer. The homogenized solution is continuously pumped to a first bioreactor for the first pH adjustment.

The soluble proteins and lipids are separated from the insolubles using a continuous separator. The separated soluble proteins and lipids are pumped to a second bioreactor for the second pH adjustment to precipitate the muscle proteins. The proteins are separated from the water and lipids by a second continuous separator.

The separated proteins can be mixed with cryoprotectants and antioxidants, if required, and frozen for storage or used immediately to develop value-added food products. The water is reused in the first step. This system can work continuously, and the flow rate can be modified by scaling up the equipment. The protein recovery yield is approximately 90 percent on a dry weight basis (Fig. 2).

Final products

The recovered products include purified and functional fish muscle proteins, fish oil, and fat-free “real byproducts” (bone, skin, scale, insoluble proteins, etc.). The recovered muscle proteins can be used to develop restructured value-added, fat-free foods. To mimic such foods and determine the quality of the recovered proteins, laboratory gels were developed.

The gels indicate that value-added marketable foods with various textures, shapes, flavors, and colors can be developed to meet market demands. The recovered fish oil can be used in food applications (nutraceuticals, heart-friendly foods) and nonfood applications (cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, chemicals). Since they are fat-free, the real byproducts can be utilized at a higher percentage in the rendering industry.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the April 2005 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Jacek Jaczynski, Ph.D.

West Virginia University

G004 Agricultural Sciences Building

Morgantown, West Virginia 26506 USA

Tagged With

Related Posts

Aquafeeds

It takes guts to advance sustainability in aquaculture

With byproducts representing between 25 to 50 percent of the weight of various fish species, we need to be looking at how the entire fish is being used: even the heads, guts and skin.

Responsibility

Integrated utilization of microalgae grown in aquaculture wastewater

A study shows that wastewater from recirculating aquaculture systems is suitable for microalgal cultivation and that sludge amendment to the wastewater increases production.

Intelligence

Byproduct utilization for increased profitability, part 1

Protease enzymes are important industrial enzymes that have diverse applications in food, leather, silk and the agrichemical and pharmaceutical industries. Fish are considered one of the richest sources of proteolytic enzymes.

Intelligence

Byproduct utilization for increased profitability, part 2

Enzymes obtained from fish- and shellfish-processing wastes can be used in the making of a number of useful products. Lipase enzymes from fish can break down lipids, while amylases hydrolyze starch.