The truth-in-labeling debate over seafood alternatives arises during Seafood Expo North America discussions

Plant-based protein and, more recently, cell-cultured protein came out of what felt like nowhere, catapulting from futuristic concept to darlings of the venture capital (VC) community to tonight’s dinner in just a few short years.

To the traditional seafood sector, namely wild-capture fisheries and aquaculture, the emergence of the alternative protein sector presents a threat to market share, even though sales of alternative seafood products pale in comparison to the $250 billion-plus global market for wild-caught and farmed seafood products. Where do plant-based and cell-cultured seafoods fit into the overall seafood community? Friend? Foe? Do the two even need to get along?

These questions surfaced at Seafood Expo North America (SENA), which returned to Boston earlier this month after a three-year pandemic-fueled hiatus. Companies producing plant-based seafood and cell-cultured seafood continue to be prohibited by the event organizer Diversified Communications from exhibiting at SENA, but for the first time this year they were featured in the event’s conference program in separate sessions titled “Rise of Cell-Cultured Seafood” and “Alternative Approach: Where the Seafood Industry Stands on Plant-Based Analogs.”

The short answer to these questions is that the alternative protein sector and traditional seafood sector are already intertwined. Many of the entrepreneurs in the alternative seafood sector come from the traditional seafood sector, and many of the companies investing in plant-based seafood and cell-cultured seafood are seafood stalwarts.

One such player is San Diego-based BlueNalu, which is developing a variety of seafood products directly from fish cells in a laboratory. Its first product will be a bluefin tuna toro. Last April, BlueNalu inked a partnership with Thai Union and Mitsubishi to assess market development strategies for the company’s cell-cultured seafood, specifically in Asia.

VC darlings

BlueNalu is just one player in the burgeoning plant-based and cell-cultured seafood space. Others include Atlantic Natural Foods, Finless Foods, Gathered Foods, Good Catch, New Wave Foods, Novish and The Plant Based Seafood Co. Perhaps the most notable as of late is San Francisco-based cell-cultured salmon producer Wildtype, which just last month locked up an all-star cast of investors, including Jeff Bezos, Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert Downey, Jr. and Cargill, all joining a $100 million funding round.

Investment in alternative seafood producers has totaled $313 million to date, including $175 million in 2021 alone, around two-thirds of which went to cell-cultured seafood producers, according to Lou Cooperhouse, co-founder, president and CEO of BlueNalu, who has 35-plus years of experience in the food business. That does not include Wildtype’s $100 million.

“There’s room for everyone. We have some of the largest meat and seafood companies in the world investing in cell culture, and a lot of companies are already collaborating,” said Cooperhouse, who was joined by Marika Azoff, a corporate engagement seafood specialist for the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit the Good Food Institute for the “Rise of Cell-Cultured Seafood” session.

Cooperhouse was asked if the traditional seafood sector is threatened by the alternative seafood sector.

“No, I see it as complementary,” he said. “Our approach from Day 1 has been to supplement. We need to work with industry. We need to feed the planet.”

One such collaboration is engaging with McLean, Va.-based trade association National Fisheries Institute (NFI) on what to call cell-culture seafood, which one can argue has an artificial connotation. According to research administered by the Good Food Institute, the name that was least confusing to consumers was, in fact, “cell-based” or “cell-cultured” seafood.

“This is fish in its pure form. It cooks the same. It’s prepared the same. It’s nutritionally the same,” said Cooperhouse.

NFI agrees: “Lou Cooperhouse reached out to us and wanted our members to understand [what his product is]. This is fish. We worked with the [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] on what it should be called, and it is going to be labeled as ‘cell-cultured.’ If you can grow out a mahi in two weeks, that’s groundbreaking technology,” said NFI President John Connelly, who participated in the “Alternative Approach” session along with Sam Galletti, president and COO of Carson, Calif.-based Southwind Foods Co.

Our approach from Day 1 has been to supplement. We need to work with industry.

Truth in labeling

Despite the industry collaboration on the cell-cultured side, there’s a sticking point on the plant-based side, and it’s a big one – labeling, specifically the need for truth in labeling.

NFI has repeatedly called on plant-based seafood producers stop labeling their products as “seafood,” which it claims is an unfair advantage. Traditional seafood producers, according to NFI, are required to adhere to a 5,000-word-seafood-labeling regulation enacted to ensure accuracy in labeling and build consumer confidence. Connelly pointed to surimi seafood products, which since their introduction in the 1970s were required to be labeled as “imitation” seafood until 2006 when the FDA finally relaxed the regulation and approved the wordy phrase “crab-flavored seafood, made with surimi, a fully cooked fish protein” on labels.

Connelly is frustrated that the FDA has not applied a similar degree of scrutiny to the labeling of plant-based seafood products as it has for surimi seafood products. He is also disappointed that some plant-based seafood producers are unashamedly labeling their products as “seafood.”

Plant-based seafood producers “are basically saying I’m going to do this until I’m told I can’t do this,” said Connelly. “The FDA needs to do its job.”

Labeling disagreements aside, both Connelly and Galletti are encouraged by the opportunities that plant-based seafood and cell-cultured seafood bring to the traditional seafood sector.

“We are a protein company. We’re involved in more than just seafood,” said Galletti of Southwind Foods, which partnered with Sophie’s Kitchen last November to offer its plant-based seafood products alongside the multigenerational seafood distributor’s traditional seafood products. “I had some struggles with this. How do you balance it? But I had to make a decision as an owner-operator that is this a good business decision. It has revenue. It has margin. I made the decision to lead versus follow.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Steven Hedlund

Steven Hedlund is the communications and events manager at the Global Seafood Alliance and previously spent many years as a seafood industry journalist.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

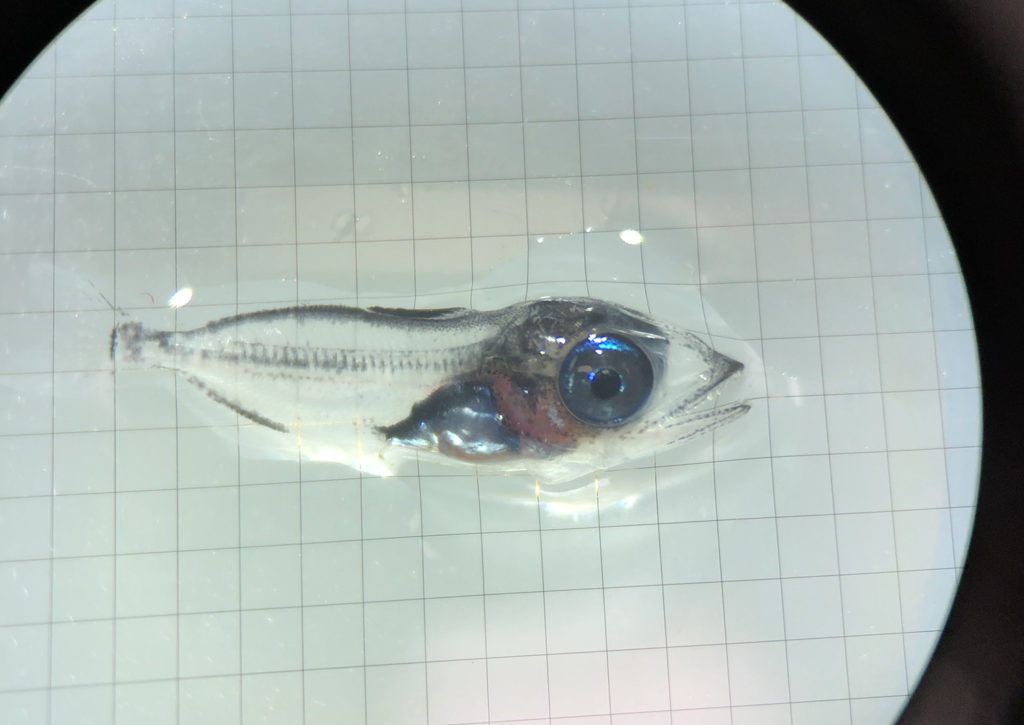

‘Not convinced it can’t be done’: A look inside California’s new bluefin tuna hatchery

San Diego-based bluefin tuna hatchery and feed company Ichthus Unlimited aims to make tuna ranching a more sustainable and reliable option.

Innovation & Investment

Hatch opens six-pack of winning aquaculture innovators at Demo Day

Demo Day in Dublin, Ireland, last week marked the conclusion of the Hatch aquaculture business accelerator’s second cohort in 2018.

Innovation & Investment

Little fish in a big pond: Minnowtech aims to give fresh vision to shrimp inventory

Because shrimp farmers lack accurate in-pond inventory, startup Minnowtech is on the verge of offering a data-driven solution. It’s got something to do with jellyfish.

Intelligence

Seaspiracy film assails fishing and aquaculture sectors that seem ready for a good fight

Seaspiracy, a new Netflix documentary-style film, depicts the fishing and aquaculture in an ugly fashion but the industry response is swift.