With ocean warming, food sources for North Pacific right whales are moving north – but so are commercial fishing fleets

As rising global temperatures push Arctic Ocean icecaps into retreat, large and small sea creatures – and the commercial fishing boats that follow them – are also migrating northward.

This mass migration toward the relatively narrow Bering Strait could lead to more ship collisions and fishing gear entanglements for the extremely rare and critically endangered eastern population of North Pacific right whales, according to a researcher at Duke University’s Marine Lab.

“There’s a really wide, shallow shelf (sea floor) that extends about 500 kilometers (310 miles) in the whale’s primary feeding ground north of the eastern Aleutian Islands off Alaska,” said Dana Wright, who is the lead author on a study that was published in Ecological Applications. “Cold meltwater from the sea ice in spring combines with currents that move up on the shelf to aggregate the zooplankton the whales eat in this area.”

For a filter-feeding whale, concentrated prey means more commercially valuable fish and some of the industrial-scale fishing fleets that follow them are moving north too.

“Ecosystem dynamics are changing,” said Wright. “Prey are responding to the changing climate, and species at the top of the food chain are too.”

Sightings of North Pacific right whales are exceedingly rare, but the animals are likely to have been moving north along with the zooplankton, according to Wright’s modeling analysis of zooplankton and temperature data collected by NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

There are two populations of right whales in the Pacific, and the eastern group found in the waters off Alaska and the Canadian Pacific is thought to number just 30 animals, Wright said.

“They were the ‘right’ whale because, for their size, they had the most oil and baleen,” Wright said. “And they floated because they had so much fat, so they didn’t have to be processed immediately.”

A critical habitat area was assigned in the southeastern Bering Sea in 2007, based on about a decade of Pacific right whale sighting data.

“So I was curious,” Wright said. “Is this going to hold up under climate change, especially since the North Atlantic right whales seem to be shifting their distribution?”

Because the whale’s rarity makes them hard to study, Wright led a study using the whale’s food to determine if the protected area was enough and whether it was in the right place. There is currently a petition from the Center for Biological Diversity pending before NOAA to expand the protected area.

“But it’s just a paper map,” Wright said. “There are no restrictions or enforcement to date, but knowing more about potential drivers of shifting distribution for these animals is an important step toward having grounds for strategic, refined protections and management.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

Related Posts

Fisheries

Gear-lending program has harvesters working through closures and trying ropeless fishing gear without commitment

Faced with closures to protect right whales, Canadian commercial fishers are trying ropeless fishing gear via the CanFish Gear Lending Program.

Fisheries

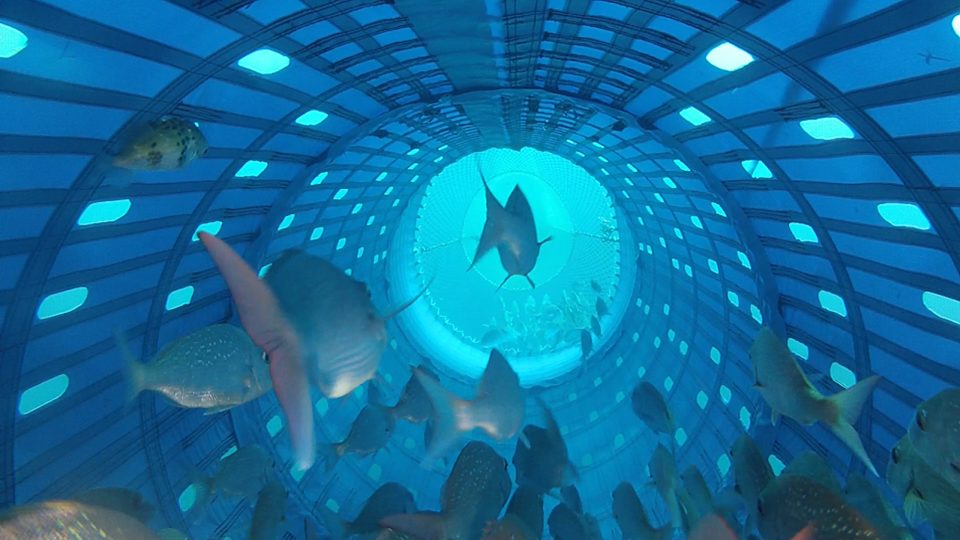

‘We were just looking for a way to fish better’: How one partnership is reinventing commercial fishing nets to reduce bycatch and improve animal welfare

Precision Seafood Harvesting’s novel reimagining of commercial fishing nets provides innovative solutions to both bycatch and animal welfare issues.

Fisheries

NOAA seeks to improve North Atlantic right whale risk assessments

NOAA Fisheries says a recent peer review of its North Atlantic right whale risk assessment tool will lead to management improvements.

Responsibility

Maine lobster industry speaks out against Seafood Watch ‘red-listing’

Seafood Watch urged consumers to avoid products from the Canadian snow crab and U.S. lobster fisheries, due to right whale entanglement risks.