Research focuses on factors that influence the larvae microbiota and approaches to increase microbial balance in rearing systems

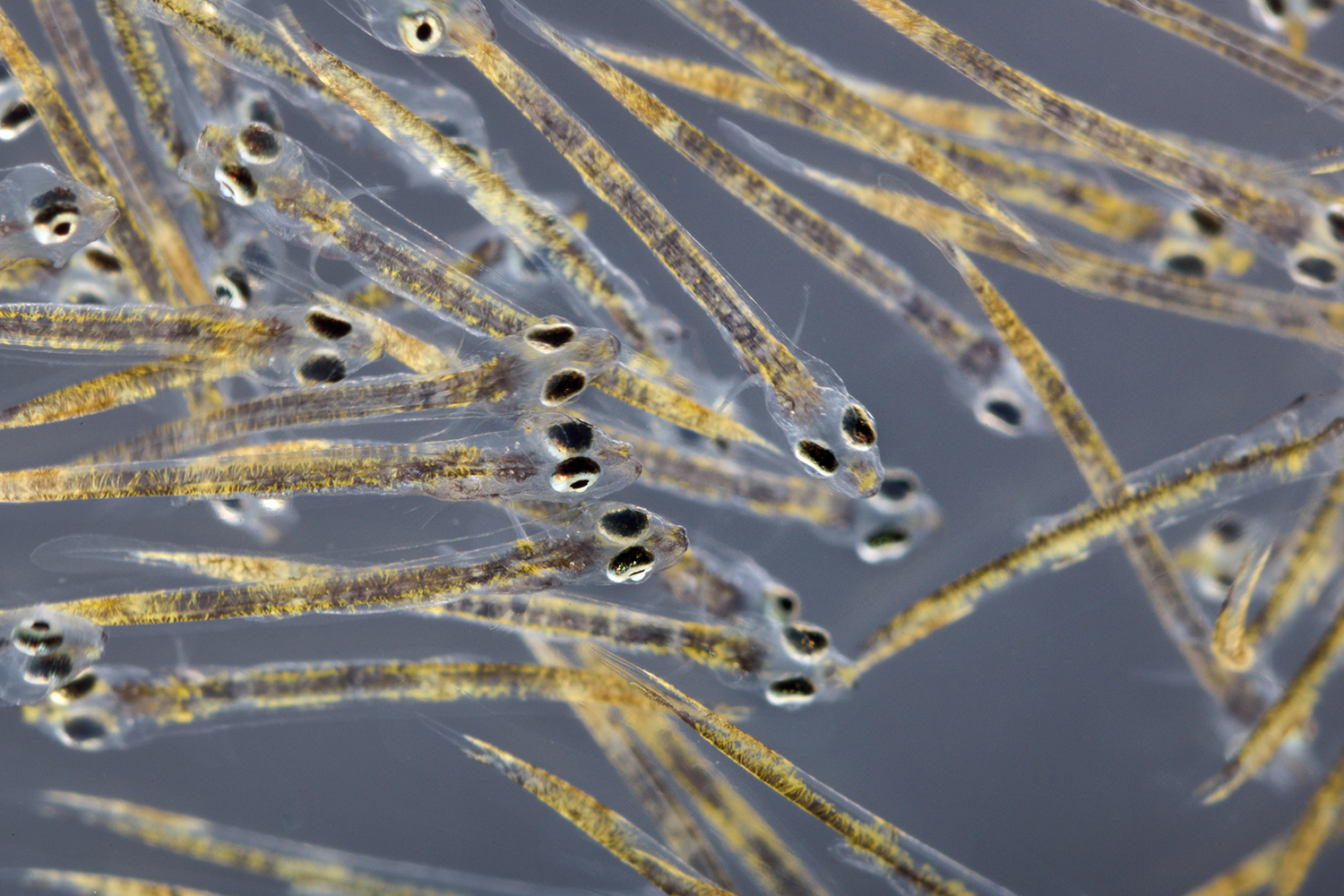

During the last decades, one of the focus areas in aquaculture microbiology has been the study of the microbiota of marine fish larvae. The microbiota of fish is crucial for host health and development, but relatively little is known about the assembly of fish microbiota during the first weeks after hatching. Gut microbiota is an important obstacle for the colonization of opportunistic pathogens in the larval gut, while marine fish larvae are vulnerable to high mortalities during the first weeks after hatching caused by the proliferation of opportunistic bacteria. The optimization of the rearing conditions that promote the development of a stable, diverse, and resilient microbiota requires the determination of the factors influencing microbial colonization.

Bacteria colonize fish skin, fins, and gills, and several studies show that members of many bacterial taxa colonize fish surfaces. The bacterial colonization of fish larvae is a dynamic process influenced by environmental and host-related factors. Detailed studies of the early fish microbiota have been conducted in a few cultured species – including gilthead seabream, yellowtail kingfish, Atlantic cod, Atlantic salmon, Senegalese sole, greater amberjack, and giant grouper – with a focus on the gut microbiota, as it is crucial for nutrient absorption, digestion, and overall health.

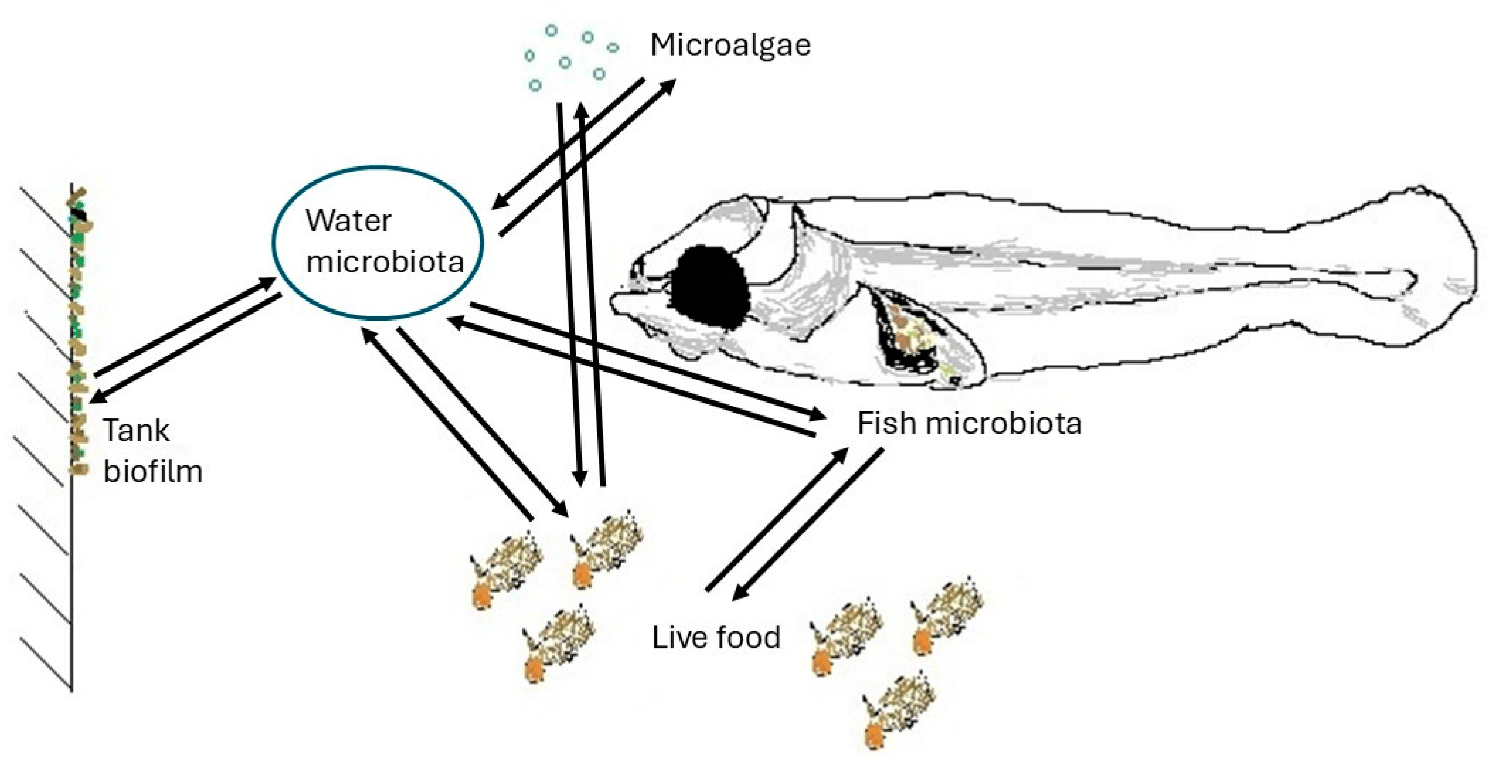

Initially, bacteria in larvae may originate from the mother fish since the fish egg microbiota influences the larval microbiota and may affect subsequent larval performance. Fish larvae drink seawater to osmoregulate, and in doing so, they ingest microorganisms present in the water, so water microbiota influence fish microbiota even before feeding starts. In the rearing of marine fish larvae, live feed organisms including rotifers, Artemia, or copepods are used. Gut microbial communities of fish larvae are affected by the type and the bacterial composition of live feed. Zooplanktonic prey organisms, microalgae, and other larvae interact continually with each other and influence the microbiota of the larvae.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Paralika, V. and P. Makridis. 2025. Microbial Interactions in Rearing Systems for Marine Fish Larvae. Microorganisms 2025, 13(3), 539) – reports on a review of the scientific literature discussing the interactions between water microbiota, live food microbiota, fish larvae immune system and gut microbiota, and biofilm microbial communities in rearing systems for marine fish larvae.

For detailed information on the literature review and analysis, refer to the original publication.

Roles of fish larvae microbiota

Fish larvae microbiota plays a crucial role in the development and health of marine fish larvae. One important aspect is the contribution of microbiota to nutrient absorption and digestion. Bacterial colonization can improve the nutritional state of fish larvae. Members of fish larvae microbiota are capable of fermenting complex carbohydrates in the larval diet, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs can serve as an additional energy source for the larvae, contributing to their overall nutritional status and reducing the intestinal pH, making the environment unfavorable for some potential pathogens and protecting the fish from bacterial infections.

Marine fish larvae often consume prey with exoskeletons containing chitin (such as artemia, copepods and rotifers). Chitin is a complex polysaccharide, and gut microbes may assist in the digestion of chitin. Dietary chitin modifies fish gut microbiota due to its prebiotic, antibacterial, and immunomodulatory properties and increases gut bacterial richness and the amount of beneficial chitin-degrading bacteria. In addition, members of the larvae microbiota may synthesize vitamins that are essential for the growth and development of the larvae.

Fish larvae microbiota offers protection against pathogens through various mechanisms that help maintain a balanced microbial community and support the overall health and viability of the larvae in rearing conditions. A first line of defense against pathogens is provided by bacteria on larval skin and mucosal surfaces of their intestine. Specifically, these bacteria compete for attachment sites and available nutrients with incoming pathogens, reducing the colonization and proliferation of these pathogens and thereby their ability to cause disease. Some microbes produce antimicrobial substances, such as bacteriocins, which are compounds that are synthesized by microorganisms to kill closely related species, or organic acids produced either through the microbial fermentation of carbohydrates from various bacterial species in different metabolic pathways and conditions or as secondary metabolites that inhibit the growth or kill unwanted marine pathogens.

Gut microbial diversity has been utilized as a biomarker of fish health and metabolic capability. Low diversity and the instability of microbiota are closely related to fish disease, as the chances for an invader to establish a niche in a high diverse environment are significantly diminished, and it is more likely that in these environments, there are members from the community with antagonistic activity. Moreover, numerous disruptions, including environmental stress, can cause illness in fish by upsetting the gut microbiota and increasing the pathogen’s virulence.

Control of bacterial infections in larval rearing systems may involve the management of potentially harmful bacteria, such as Vibrio spp., in the seawater of the rearing system. Seawater serves as a common medium for larvae, live feed, microalgae, and the rearing environment (including sediment, tank walls, pipes, etc.), where its microbial dynamics interact with those of the larvae, live feed, and environmental surfaces.

How phospholipid sources impact growth, health and gut microbiota of female Pacific white shrimp

Factors influencing fish larvae microbiota

Various factors are relevant, including host selection and developmental stage, diet, water microbiota, and biofilms.

Host selection and developmental stage

The bacterial dynamics associated with the early developmental stages of fish larvae are complex and influenced by various factors, including the surrounding environment, maternal influences, diet, and developmental changes in the larvae. As fish larvae develop, their digestive and immune system changes, which can influence the dynamics of the gut-associated bacterial communities. During development, gut morphology and function change influencing bacterial colonization patterns, including the types and the abundances of bacteria. The bacterial diversity in fish larvae tends to increase gradually with age until it peaks when approaching the juvenile stage.

Extrinsic (diet, water quality, rearing environmental physicochemical parameters, etc.) and intrinsic (trophic level, genetic background, gender, age, etc.) factors modulate fish larval microbiota. During the early larval developmental stages, the gut microbial community is generated by species-specific selection. The presence of a core microbiota in fish species, reared in different environments or across different dietary conditions and time series indicates that host selection is a major factor affecting microbial composition.

Diet

Fish larvae eat various zooplanktonic organisms in the wild, primarily copepods. In marine aquaculture systems, the conventional feeding–rearing protocol consists of zooplankton. The production of highly nutritious live food is one of the most critical parts of successful larvae rearing, as it influences not only larvae growth but also the development of deformities, malpigmentation, as well as overall health and hence survival. Given that the gastrointestinal tract is one of the main entry points for various pathogens, it is crucial to assess the impact of dietary microbial communities on the intestinal microbiota of fish. Since live food production in larval hatcheries has become more intensive, the spread of disease has become a serious concern. It is widely known that, in larval cultures, live feeds may transmit opportunistic and putative pathogenic bacteria.

Water microbiota

Together with live food microbiota and microalgae, water microbiota shapes the microbial profile of the reared larvae. Microbiologically, water quality is not easy to define, as it is characterized by both the quantity and the quality of the microbial communities present. The quantitative part has traditionally been in focus, and the continuous reduction of the bacterial load is the main approach in marine fish hatcheries. The qualitative characteristics of the water microbiota are, however, more important, which are nevertheless difficult to assess, except for the presence or absence of well-known pathogens.

A theory that may be used to define microbial water quality is based on the r/K strategy; bacteria are assigned into two functional groups, r- and K- selected bacteria, respectively. K-strategists grow slower, are in dense areas with increased competition for resources, and tend to create more stable communities. Microorganisms following the r-strategy are found under the opposite spectrum of these conditions, and opportunistic pathogens often follow this mode. This approach has been applied to assess and steer microbial environments in larval rearing, and it appears that opportunistic species are mostly responsible for parasitic host–microbe interactions. It is advantageous to establish a stable microbial community in the rearing system that is dominated by K-strategists, while opportunistic strategists will benefit from the use of antimicrobial agents and disinfection, which will create new niches.

Biofilms

After a solid surface is first exposed to seawater, dissolved organic matter adheres to it and creates a thin film (<100 nanometers) known as “molecular fouling” in a matter of seconds. Multiple factors influence the composition and structure of biofilm microbial communities, such as niche differences, water quality changes, the availability of inorganic nutrients and organic matter resources for organisms, water depth and biofilm age, substrate surface properties, and temperature situation. The colonization of solid surfaces and the formation of biofilms is advantageous for some bacteria, as biofilms resist desiccation, improve antibiotic resistance, have a higher nutrient concentration, and show a better defense against predators.

In aquaculture rearing systems, bacterial biofilms may harbor opportunistic pathogenic bacteria and serve as a reservoir for those microbes that may colonize the water column, which could make them a constant source of bacterial infection for the rearing species. Bacteria within the biofilm are useful for recycling nutrients and eliminating unwanted ones from the system, reducing toxic inorganic nitrogen through nitrification and heterotrophic bacteria, and enhancing fish and shrimp growth and survival.

Methods used to analyze fish larvae microbiota

The study of microbial communities in fish can be based on culture-dependent or culture-independent methods. The culture-dependent methods allow bacterial identifications to the species level and one of its main implications is that culture-dependent methods can validate findings from culture-independent approaches by confirming the presence of specific microorganisms and providing isolates for further study such as the isolation and identification of bacteria, which have been characterized as potentially probiotics.

Studies on fish larvae microbiota focus on explaining the fundamental processes for functioning, aiming to develop innovative approaches for managing microbial populations. This requires the identification and characterization of the microbial communities of all the different parts of the rearing systems. The massive quantities of microbes in these systems could only be detected by new molecular tools, which are referred to as culture-independent methods and involve directly extracting DNA or RNA from a sample without the need for microbial cultivation (Table 1).

Makridis, Microbial interactions, Table 1

| Method | Characteristics of method |

|---|

Method | Characteristics of method |

|---|---|

| Culture-based Methods (Classical microbiology) | Many bacteria are non-culturable. Identification based on cell morphology or physiological tests time- and labor-consuming and many times impossible to identify isolates at species level. |

| Biochemical Tests | Bacteria may have variable or weak reactions, leading to misidentification. Difficult to distinguish closely related species with similar metabolic profiles. |

| PCR-Based Identification (16S rRNA Sequencing, Multiplex PCR) | 16S rRNA sequences may not differentiate closely related species. PCR inhibitors from environmental samples can affect results. Requires specific primers, which might not cover all bacterial taxa. |

| Metagenomics and Shotgun Sequencing | High cost and requires bioinformatics expertise. Short-read sequencing can lead to assembly errors. Contamination can mislead taxonomic classification. |

| Flow Cytometry and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) | Requires specific probes for known bacteria. Less effective for detecting rare or unknown taxa. Labor-intensive and requires expensive equipment. |

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was introduced in the early 21st century. NGS has made tremendous development by allowing the rapid and cost-effective creation of massive volumes of data, with superior accuracy in DNA sequencing compared to earlier methods. At the moment, all NGS approaches require library preparation. They are widely used for profiling microbial communities in environmental samples, including fish larvae, and studying microbial diversity, community structure, and functional potential. Additionally, they provide a comprehensive view of microbial diversity, including uncultivable and rare microorganisms. NGS approaches enable the high-throughput analysis of microbial communities, allowing for the simultaneous profiling of multiple samples.

Perspectives

The study of microbial interactions in larval rearing systems has focused on the factors that influence the microbiota of the larvae, possible approaches to increase microbial balance in larval rearing systems, and the use of probiotics in larval rearing to improve survival and growth of the larvae. In earlier days, these approaches and their effect on the microbiota of water, fish, and live food were monitored by classical microbiology, which was a very laborious and highly inefficient process. Now, with the use of molecular techniques, it will be easier to obtain some more clear answers to the same questions. In addition, with the emergence of new live food organisms, such as cirriped larvae or easily available copepods, the effect on fish larvae microbiota will be far more reliably assessed.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Dr. Pavlos Makridis

Corresponding author

Department of Biology, University of Patras, 26504 Rio, Greece

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Barcoding, nucleic acid sequencing are powerful resources for aquaculture

DNA barcoding and nucleic acid sequencing technologies are important tools to build and maintain an identification library of aquacultured and other aquatic species that is accessible online for the scientific, commercial and regulatory communities.

Innovation & Investment

A novel chromosome-level genome assembly of the Pacific white shrimp

A genome assembly of L. vannamei provides valuable resources for future genetic research, breeding and improvement of traits for aquaculture.

Innovation & Investment

Artemia, the ‘magic powder’ fueling a multi-billion-dollar industry

Artemia, microscopic brine shrimp used as feed in hatcheries, are the unsung heroes of aquaculture. Experts say artemia is still inspiring innovation more than 50 years after initial commercialization. These creatures are much more than Sea-Monkeys.

Health & Welfare

Microbial colonization in the early developmental stages of the black tiger shrimp

Microbial colonization in developing P. monodon could be shaped by different host developmental stages, diets, physiologies and immune statuses.