Protect health with water filtration, pond netting and use of domesticated stocks

Regular surveillance provides information on the health status of farmed stocks. It can also provide information on possible future disease outbreaks by detecting increases in the prevalence of endemic pathogens or the presence of exotic pathogens. Their early detection can allow intervention and control measures before disease outbreaks occur.

Early detection

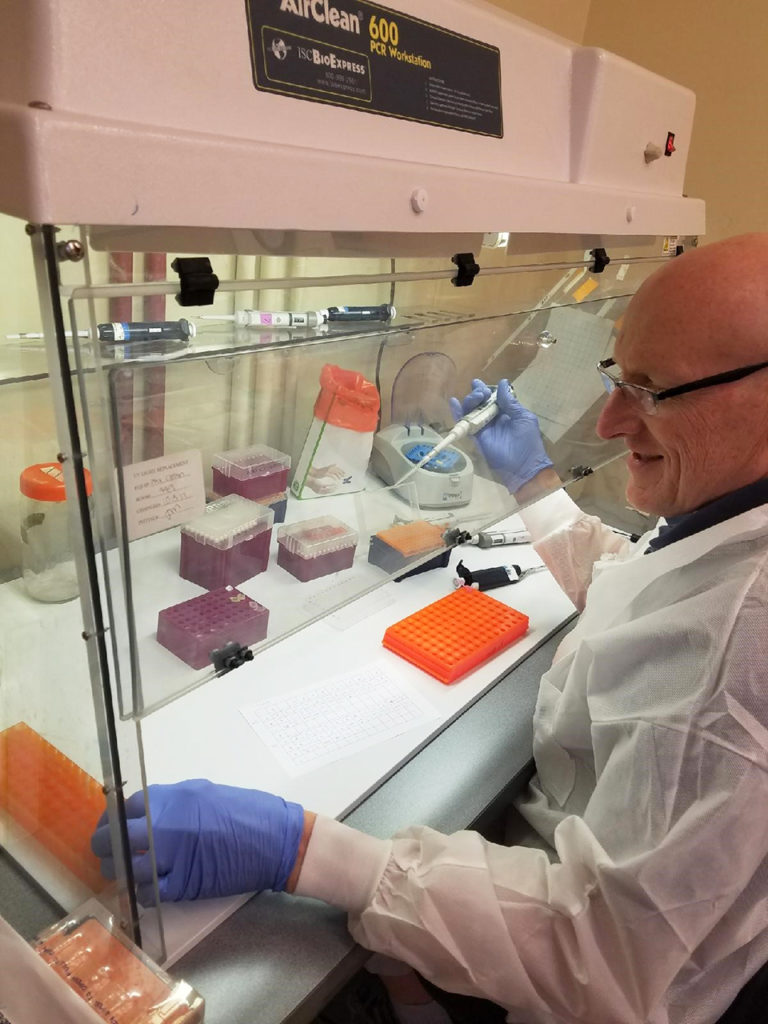

Surveillance can be focused on known or unknown pathogens, or a combination of both. For known pathogens, polymerase chain reaction techniques should be applied. Each farm should determine its own list of important diseases to protect against. In addition to other criteria, this list could be based on the economic impacts of the diseases, means of transmission and presence of susceptible species.

For unknown pathogens, histology is required. Histological changes, even if the causative agent cannot be identified, should raise the attention of the farmer. If there is an increase in the prevalence of these changes, they may reflect the build-up of an epidemic.

Improving performance

The line that separates healthy and sick animals in aquaculture is rather blurred. From the point of view of a farmer, health is a measure of productivity. If a disease does not cause unexpected loss of income, it may not be regarded as a disease concern. However, chronic diseases that reduce growth and survival have a significant cost to the industry.

Often, results of diagnostic tests are used for immediate application of management practices, such as stocking or discharge of postlarvae, emergency harvest or exchange of water. However, this information can also be used for medium-term management. Some epidemiological studies indicate that a random whole farm sampling for all pathogens could be more advantageous than a thorough follow-up on a small number of ponds.

When surveillance detects pathogens such as hepatopancreatic parvovirus in Thailand or infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus in Latin America, or risk factors associated with low productivity, a targeted sampling could be implemented as a monitoring program in following cycles. Such programs could optimize the value of the diagnostic information and identify ways to improve production.

Biosecurity needed

In an interesting paper on the emergence of viruses in Australian prawn aquaculture published in 1997 in the World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, Dr. Leigh Owens of James Cook University in Australia presented the detection of a number of viruses in wild shrimp, wild-caught broodstock and farmed shrimp within a time frame (Table 1).

Alday-Sanz, Dates of detection of shrimp viruses, Table 1

| Virus, Condition | Wild Shrimp | Wild Broodstock | Aquaculture |

|---|

Virus, Condition | Wild Shrimp | Wild Broodstock | Aquaculture |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA proliferative syndrome | 1980 | ||

| Hepatopancreatic parvovirus | 1984 | 1988 | |

| Monodon baculovirus | 1984 | 1986 | 1986 |

| Lymphoid organ vacuolization | 1988 | 1990 | |

| Lymphoidal parvovirus | 1989 | 1990 | |

| Infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus | 1989 | 1991 | |

| Penaeus hybrid rod-shaped virus | 1989 | 1991 | 1996 |

| Gut and nerve syndrome | 1993 | ||

| Spawner-isolated mortality virus | 1993 | 1994 | |

| Lymphoid organ virus | 1995 | 1995 | |

| Bennettae baculovirus | 1995 | ||

| Midgut caecum inclusions | 1990 |

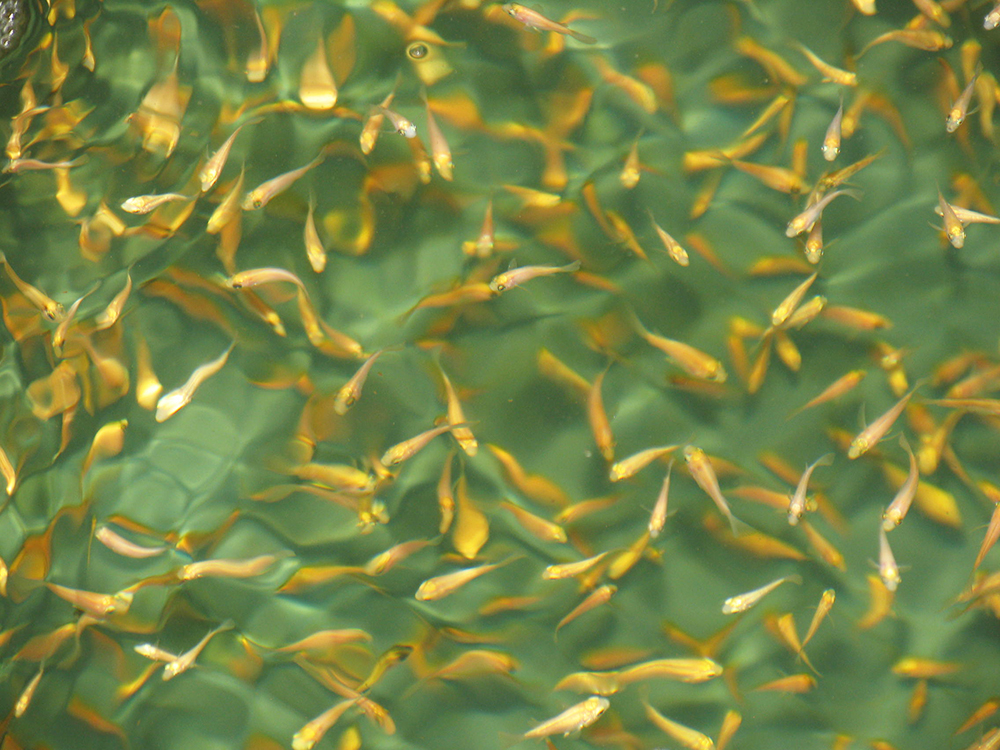

The paper showed that early in Australia’s aquaculture history, the detection of all viruses was preceded by their discovery in wild prawns from the fisheries, highlighting the risk of introducing wild broodstock to farm facilities. Once pathogens are introduced to farms, they find an ideal environment for replication, spread and potentially lead to disease outbreaks.

The health status of culture species can therefore be protected through improvements in water filtration, pond netting and the use of only domesticated stocks. While new viruses will be discovered in the future, only by closing the life cycle and improving biosecurity can we start excluding pathogens from aquaculture production in the present.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the March/April 2009 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Victoria Alday-Sanz, Ph.D.

Aquatic Animal Health

Gran Via 658, 4-1

08010 Barcelona, Spain

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

A comprehensive look at the Proficiency Test for farmed shrimp

The University of Arizona Aquaculture Pathology Laboratory has carried out the Proficiency Test (PT) since 2005, with 300-plus diagnostic laboratories participating while improving their capabilities in the diagnosis of several shrimp pathogens.

Health & Welfare

A holistic management approach to EMS

Early Mortality Syndrome has devastated farmed shrimp in Asia and Latin America. With better understanding of the pathogen and the development and improvement of novel strategies, shrimp farmers are now able to better manage the disease.

Responsibility

Aquaculture certification steers to zone management

Zone management is an emerging field of interest among industry stakeholders. Experts say it will aid in controlling diseases and in determining carrying capacities. We take a closer look at the management tool’s potential.

Health & Welfare

Biosecurity practices on fish farms need beefing up

Biosecurity measures and preventive strategies are essential in any biological production chain. Properly planned and implemented biosecurity programs will enhance animal health, production and economics.