Consumers must learn more about food production to change their behavior

How can we have 800 million starving people and at the same time have obesity in over one-third of the global population? We have sufficient food. We have nutritious food. Yet malnutrition and obesity are affecting people globally.

When World War II concluded in 1945, there was much food scarcity, but since then, the world has changed. Of course, there are still pockets of shortages, but generally speaking, we have moved away from food shortages. Technology and innovation in production have improved crops and yields immensely.

People of the Pacific nations, for example, are suffering from obesity. More than 30 percent of Fijians are obese, and, amazingly, American Samoan women have an obesity rate as high as 80 percent. Even in Indonesia, and in fact many developing countries, there are more overweight than underweight women. That effect is seeing a doubling of the burden of disease.

With significant numbers of people undernourished and an increasing number of people overweight, specialists are saying surely something is not right with our system. While there are theories on how to solve the issues, no one has really found a workable solution. Health departments have failed fairly dismally, and this has resulted in more issues, with non-communicable diseases such as diabetes taking limbs and lives along the way.

Sydney conference

The “Resetting the Australian Table: Adding Value and Adding Health” conference recently held in Sydney, Australia, engaged a number of specialists who not only raised the issues, but endeavored to find solutions to the mounting problems.

Professor Jonathan Rushton from the Royal Veterinary College at the University of London was quoted as saying “Just as farmers care about what they feed their animals, they should care about how their food is processed.”

Rushton said annual global average meat consumption has nearly tripled in 50 years – from 25 to 62 kg/person – and people are increasingly disconnected from its production. However, meat consumption hasn’t changed a great deal in Australia. In the 1960s, annual consumption was 100-110 kg/capita. Consumers have shifted form eating sheep and cattle to eating more pigs and poultry.

“When I travelled between Melbourne and Sydney, what I didn’t see was pigs and poultry out in the fields,” he said. “Those systems are hidden from you. You don’t see what they’re being fed. There is a disconnect between the urbanized population and food systems.”

Rushton described the food system as rotten, and said farmers have become part of a world driven by stock-listed companies that respond to shareholder values.

Changing behavior

At the same event, Associate Professor Robyn Alders of the Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Veterinary Science at the University of Sydney suggested that food system problems can no longer be only for health authorities to solve, but that the whole of society needs to engage and assist with solutions.

Alders, who has long worked in international agricultural aid in Africa and Asia, reportedly said: “If we feed our pigs ad lib they will get too fat to stand up, but we are doing that to ourselves. You have ongoing significant numbers of people who are undernourished and an increasing and significant number of people who are overweight.”

The divide between recommendations and results is marked, but not all that uncommon, be it about a diet or a business. In a world seemingly overrun with data, analysis and experts, what people say we should do and what actually works can be like ships passing in the night.

Sociologist Dr. Jane Dixon of the Australian National University explained that her doctorate work looked into the rise of chicken in our diets, saying it met all the supermarket criteria as convenient, cheap and offering choice.

Dixon said chicken has been marketed as a healthy, low-fat meat, winning the National Heart Foundation’s tick of approval. Australian consumption of chicken has doubled to 43 kg/person/year. She told the conference that “we are contradictions” and are buying the wrong chicken, highlighting that when coated in batter and deep fried, chicken’s goodness is undone.

Paleo diet

The “Paleo diet” has been taking the world by storm. An industry has been created where there was none. Books, magazines, blogs, podcasts and retreats have been spreading the idea that eating what cavemen ate – lots of meat, fish and plants; no grains, sugar and dairy products – is the path to weight loss and better health.

Most cavemen died by the age of 25 but, of course, things were different back then. High infant mortality was a dramatic contributor to this pattern, but the fact remains that few made it anywhere close to the modern life expectancy of 75 to 80 in western countries.

The divide between recommendations and results is marked, but not all that uncommon, be it about a diet or a business. In a world seemingly overrun with data, analysis and experts, what people say we should do and what actually works can be like ships passing in the night.

Perspectives

The solutions we seek must be responsible and sustainable. We must seek hard evidence and promote those facts. The Paleo diet sounds intriguing – and parts of it might even be right – but it makes sense to see how it actually does in practice. It may or may not be for you.

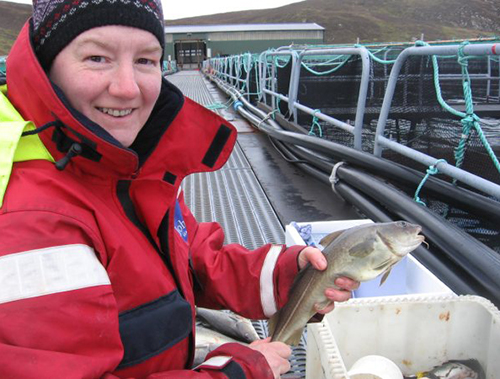

Aquaculture will be front and center at the GOHWell Summit – February 4-6, 2016 in Melbourne, Australia. Fish feeds and diets will be discussed in detail. It is important that we do not fall into the same trap as pork and chicken.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Roy D. Palmer, FAICD

GILLS

2312/80 Clarendon Street

Southbank VIC 3006 Australia

www.gillseafood.com

Tagged With

Related Posts

Intelligence

Warning: Shrimp salad may contain shrimp

Crustaceans, fish and any food that contains protein have the potential to cause allergic reactions in some individuals. To protect consumers, seafood businesses must stay abreast of changing regulations.

Intelligence

Brazilian aquaculture: Constraints and challenges (Part 1)

The Brazilian aquaculture industry has been growing steadily during the last two decades. Despite facing a number of challenges it is looking at continued growth and a larger role in the export markets.

Innovation & Investment

Aquaculture Exchange: Dawn Purchase, part 2

The Marine Conservation Society’s aquaculture program manager discusses what consumers ultimately need to know about aquaculture, responsible production and eco-labels. She also looks at NGOs making a difference in the global seafood industry and where she finds innovation in action.

Intelligence

Making the case for a seafood-based economy

The “Towards a Seaweed Based Economy” report made the case that poor nutrition is the major cause for the pandemics of obesity and several chronic diseases. It recommended increased use of food-production systems like integrated multi-trophic aquaculture.