Global Fisheries Innovation Award finalist: Precision Seafood Harvesting

In 2011, a group of researchers at the New Zealand Institute for Plant and Food Research attached cameras onto commercial fishing nets and dropped them into the ocean. Initially, the team was just curious to observe how the fish performed within the trawl net, but what they saw was eye-opening.

“The fish in the traditional mesh nets were quite tired and exhausted,” said Dr. André Pinkert, General Manager Commercial at Precision Seafood Harvesting (PSH). Originally a Primary Growth Partnership between the New Zealand government and three local seafood companies (Moana New Zealand, Sealord Group and Sanford Limited) to develop new fishing technology, PSH is now a commercial entity with the aim to make the technology accessible to fishermen worldwide. “They were trying to outswim and cope with the water velocity. At some point, they just migrated to the end of the net, and then [had] a lot of contact with the net and other fish. Not the nicest environment.”

Bouncing against each other and rubbing against the net, such close contact caused damage to the fish, with the scientists noting visible blood spots and bruising on their bodies. From these experiments, a weighty question emerged: Can we fish with greater care and improve catch quality?

“They were thinking, we’ve been fishing like this for hundreds of years,” said Pinkert. “Is there a better way to fish?”

Currently, more than 80 percent of fish are caught via fishing nets, which largely involves swooping up a school of fish using giant mesh nets. But that could change: PSH has reinvented the cod-end (or the terminal end of the traditional fishing net where all the fish congregate), developing a system of large flexible liners that contain the fish and allow them to comfortably swim within the net during the trawl.

It took seven years, four project partners, (NZ) $43 million (U.S. $25 million) and more than 10,000 experimental tows, but the modular harvesting system (MHS) with an intelligent design not only improves fish welfare during harvesting, but also optimizes catch quality and offers potential to reduce bycatch. And with higher quality comes a higher return for fishermen.

With prospects to benefit fish stocks, the environment, consumers and the global seafood fishing industry, this novel harvesting and fishing technology could change the way the world fishes. For this contribution, PSH has been named one of the three finalists for the Global Seafood Alliance’s inaugural Global Fisheries Innovation Award as determined by GSA’s Standard Oversights Committee. The winner will be announced at the organization’s GOAL conference in Seattle next week.

Trawling for solutions

Unlike traditional mesh nets, PSH modules are made from sheets of composite material and are designed to “tailor the in-trawl environment to the physiological tolerances of the fish.” The technology replaces the lengthener and cod-end sections of a mesh trawl net and can be retrofitted to existing gear. However, the holes, said Pinkert, are the “secret sauce” of the technology.

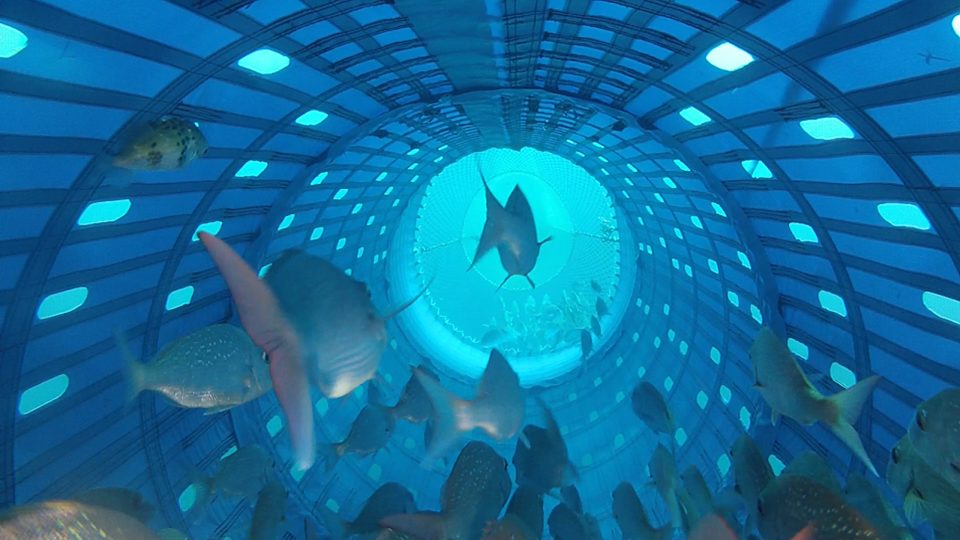

“Imagine a tube that’s made out of a membrane with little holes in it, where the water and the small juvenile fish can escape,” said Pinkert.

Inside the tube, a fish can relax and swim freely in a low-flow environment, and small unwanted fish can escape unharmed and without exhaustion. Aside from providing an escape hatch, the openings are also placed at “very specific locations” to create an even flow that slows down the water velocity.

“A lot of fluid dynamics modeling had to be done to understand where we have to put those holes in the net to keep it inflated all the time,” said Pinkert. “But also make sure that the water flow in the net is laminar, as opposed to a mesh net where we found there’s lots of turbulence within the net. That’s a large component that tires the fish out.”

With individual fish species behaving differently inside the nets, the size and placement of the escapement holes can also be tailored to increase the species and size selectivity of the catch.

“What we’ve found in our studies is that different types of fish behave differently within the net,” said Pinkert. “Some congregate in the middle of the net, others will hover more towards the outside of the net. If you understand the behavior of the fish, there’s the potential to make the escapement holes in places and shapes and forms that favor more one species than another one.”

Although Pinkert says there’s “still work to be done” on refining the technology, early results look promising. With this system, fish are brought on deck still swimming inside the liner in perfect condition – which means fresher fish for consumers and higher value products for fishing companies using the system.

“Imagine once you bring the fish up on board – it’s lively, fresh, not damaged,” said Pinkert. “You have a much higher-quality catch. We compared bruising, blood spots and scale loss to traditional mesh nets and that was very, very different – up to the point where some of the fish that we brought up had a completely different skin color than with traditional nets.”

With traditional fishing nets, the longer fish stay in the net, the more damage they get. So often fishermen are faced with a dilemma: Fish longer and get a bigger catch with a lower quality? Or go for a smaller catch with a higher quality?

“With our nets, you don’t have to make that choice anymore because the fish are not fatigued in the net,” said Pinkert. “They’re like in an aquarium, so you can fish larger volumes of fish without compromising on the quality.”

The MHS also allows fishermen to quickly process the catch. With traditional fishing nets, fishers will often allow a second net filled with fish to “soak” in the water while they process the first. But this practice gambles with the quality of the catch – or risks losing it altogether.

“With our reinvented nets, you can do the soaking for really long times without worrying about the degradation of the fish,” said Pinkert. “Those are two massive benefits for fishermen.”

Aside from a “not nice” environment and the risk to fish quality, fishing with traditional nets also brings another problem: bycatch. However, the MHS allows for net designs that leverage the natural in-trawl behavior of different fish species to reduce the unintentional capture of non-target marine species.

“If you know what species you’re fishing for and the legal minimum sizes, then you can make the escapement holes just that size that the juveniles can swim out,” said Pinkert.

With this technology, the team has also found reduced interactions with sea birds, which may swoop in when bringing the net up on the top, and in other protected species, like dolphins or sea lions.

“The net is not full of holes, like a mesh net; it’s more like a membrane with escapement openings,” said Pinkert. “So there’s much less opportunity for those species to interact.”

‘Greater control for fishermen’

As for next steps, the joint venture partners (Plant and Food Research, Sealord, Sanford and Moana) have formed a company (Precision Seafood Harvesting Ltd.) to further develop the technology to the end user and to prepare for international commercialization. This will also include novel catch-sensing mechanisms and the ability to release the catch underwater during the tow if needed (e.g., if a dolphin or sea lion is detected in the net).

With support from the New Zealand government and an additional (NZ) $9.5 million (U.S. $5.5 million) of funding, the team is now looking for international partners for further trials and to set up a global supply chain. But one challenge for moving forward on a commercial level is updating regulations.

“Because our nets are not made out of mesh, they don’t fit with any fishing regulations,” said Pinkert. “They have to change the regulations. That has happened in New Zealand, but that would also have to happen overseas before it can be used.”

To date, the system has received approval for commercial use in New Zealand. To achieve this, it had to pass strict criteria for size selectivity, species composition, benthic impacts and protected species.

“Today, fishermen put the net in the water, they have some sort of sensors in there, but there’s still a lot of guesswork involved,” said Pinkert. “They don’t really see what they have until the net is up – and then it’s too late because they can’t put it back. We want to change that and give the fishermen more control over the way they catch fish.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Lisa Jackson

Associate Editor Lisa Jackson lives in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Her work has been featured in Al Jazeera News, The Globe & Mail, The Independent, and The Toronto Star.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Fisheries

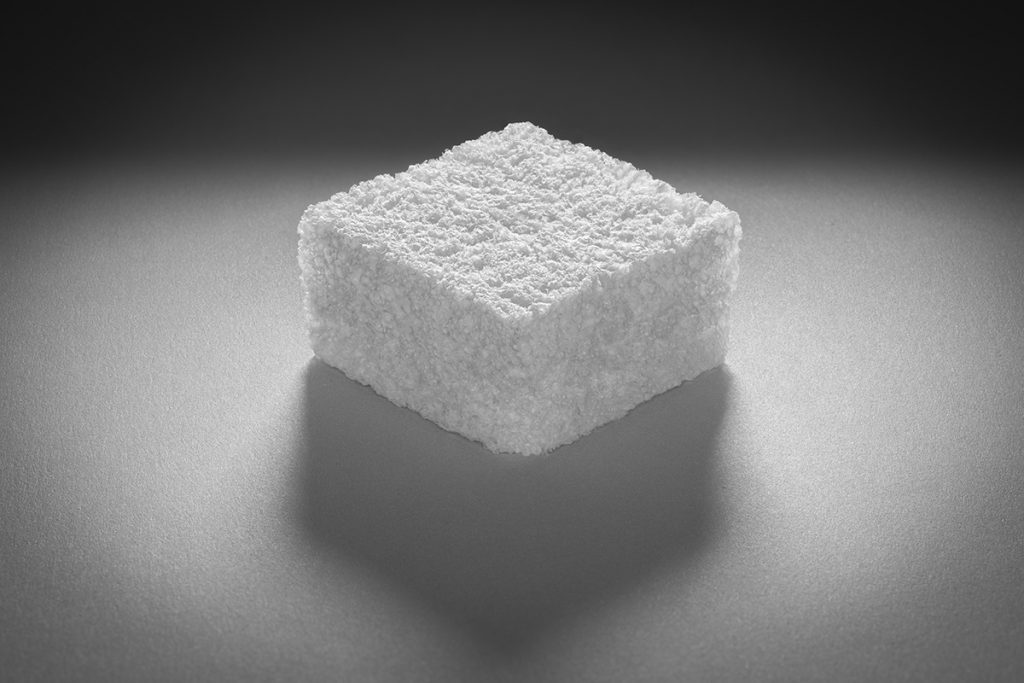

‘Regulation is pushing toward greenifying materials’: How one innovator is upcycling seafood waste into biodegradable packaging foam

GOAL 22: Cruz Foam’s biodegradable packaging foam made with shrimp shells is a finalist for GSA’s inaugural Global Fisheries Innovation Award.

Innovation & Investment

‘They know better than men how to protect their environment and people’: How focusing on women farmers is boosting food security in India

GOAL 22: The Government of Odisha and WorldFish collaborate to boost income and food security in India by teaching women’s groups to raise carp.

Fisheries

‘They need a good reason to stay’: How one coalition may break a decade of deadlock in the North Atlantic mackerel fishery

GOAL 2022: The North Atlantic Pelagic Advocacy Group, led by Dr. Tom Pickerell, is a finalist for GSA’s inaugural Global Fisheries Innovation Award.

Innovation & Investment

‘Choices are limited when searching for alternatives to antibiotics’: How one veterinarian is employing bacteriophages to fight Vibriosis in shrimp farming

GOAL 2022: Bacteriophages can overcome antibiotics in aquaculture's fight against Vibriosis in shrimp farming, and Dr. C.R. Subhashini is leading that fight.