Lessons learned from Japan’s experiences

We sometimes get trapped by “isolated optimization” and lose sight of the whole picture. Too often this applies to managers and persons in charge of specific divisions in regional and national government. To regain perspective, “get out of your silo” and take holistic views and approaches.

All environmental problems are interconnected, and in many cases, drive vicious feedback loops, worsening the situation. This involves waste, of course, but also water, climate change, biodiversity loss, shrinking forests and coral reefs, and all kinds of pollution. Such interlinked problems cannot be solved by an individual division or a single sector.

Ultimately there are only two kinds of environmental problems. One type comes from the “source side,” pushing the earth to provide us with more and more resources and energy to feed constant economic growth. This pressure has created issues such as shrinking forests, loss of biodiversity and soil erosion. Another kind of environmental problem is on the “sink side,” emitting more garbage, carbon dioxide, ozone-depleting substances and other pollutants than the earth can absorb and detoxify.

Needless to say, sources and sinks are also linked. The more we take out of the earth, the more waste we produce. So waste management has a strategic function, not only for doing something with garbage, but also for solving many other issues.

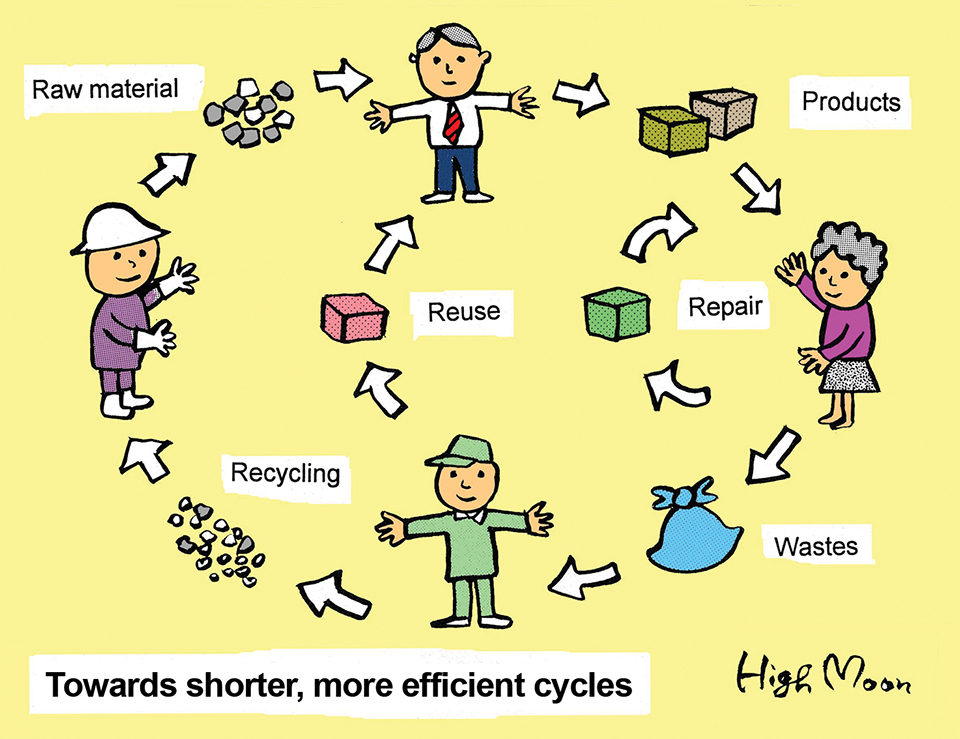

In order to recycle properly, waste should be collected, sorted and processed back into raw materials. When we started recycling efforts in Japan many years ago, things stopped too soon. The more recycling we did, the more raw materials were produced. But they piled up in the stockyards of recyclers. The loop was not closed!

In order to close the loop, we need manufacturers to use raw materials that came from recycling their products. We also need consumers to buy products made of recycled materials. This work will be more effective when people, organizations and sectors beyond a narrow definition of waste management are involved.

Expect what growth brings

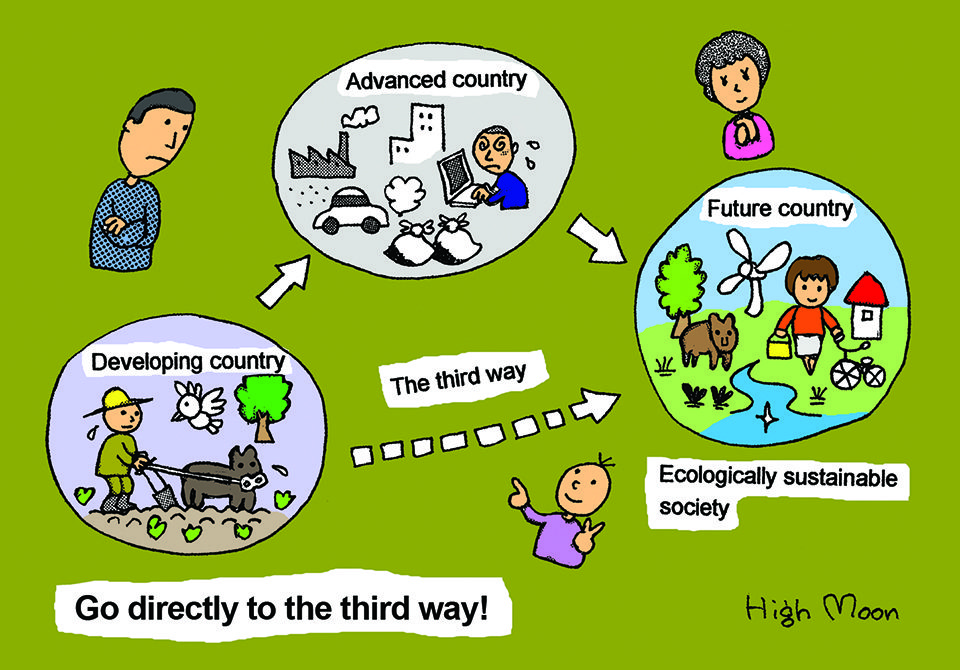

Many developing countries in Asia and the rest of the world are at a crossroads. They don’t have to repeat the mistakes made by Japan and other countries that developed earlier, but they do have to address the problems they already created during economic development.

Developing countries can leapfrog through the process, learning from others. Put recycling and other effective and efficient waste management systems in place early. Creating a system before you face huge piles of waste is much easier and less costly than after you find yourself in a jungle of waste.

Focus upstream

Struggling with waste. Recycling. Building waste treatment facilities. Reclaiming coastal land for a landfill waste dump. In addressing such issues, it is better to focus on things upstream rather than running around frantically downstream.

Focusing upstream means working with manufacturers, because it is they who decide how future waste will be produced. Encourage them to “design for the environment.” Improve reusability and recyclability, focusing on the ease of disassembly. Urge manufacturers to consolidate the kinds of materials used.

Japan has various eco-product awards that motivate companies to advance technological innovation and development. The key is to co-create new business models in which manufacturers and consumers can be better off with sufficient production and sufficient consumption.

Focusing upstream also means working with marketers and retailers, because they decide how would-be waste items are promoted and sold. Focusing upstream also means working with consumers, because they ultimately decide how much and what kinds of waste they produce.

We have to think about what we can offer consumers other than consumption to meet their needs for identity and a sense of happiness. This challenge applies in developed countries, as well. People consume things not only for physiological and safety needs, but also belonging and self-esteem needs.

One alternative approach is to continue letting consumers use what they want for their identity and happiness, but by leasing the physical goods instead of owning them. In other words, people pay only for the utility value of a product, rather than buying the product itself. This approach might lead to less material “needed” and less waste.

Foster social capital

In the Japanese cities of Minamata and Yokohama, officials created opportunities for citizens to gather together, sort their garbage and discuss what they should do to reduce waste. Such waste management interventions targeting citizens have produced dual benefits.

One is a higher recycling ratio and less waste to be treated, as expected. Another less noticeable benefit, which was not targeted initially, is fostering social capital in the community. It has stimulated many community activities and initiatives. Local non-governmental organizations have been born and strengthened, and this is very important.

In Japan, sharing has become a big boom. It is also good business.

Retaining easier than losing and regaining

During the Edo Period (1603 to 1867), Japan had a closed-door policy that cut off relations with all other countries. It had a stable population throughout the period at about 30 million people. The city of Edo (now Tokyo) had a population of about 1 million people, and it was self-sufficient in everything. It was a time of peace. The economy and culture flourished. A truly sustainable society existed.

Specialized businesses would purchase waste paper, used clothes and used pails. There were even businesses that bought the wax drippings from candles to make new candles to sell. Other businesses would buy the ash left from burning wood fuel and sell it to farmers as fertilizer. Human waste from the richer neighborhoods apparently went for the highest prices because it had the highest nutrient content!

Perspectives

Ryoanji Temple in Kyoto has an ancient hand-washing basin engraved with this message: “A man who knows that he has enough is rich even when he is poor. A man who doesn’t know that he has enough is poor even when he is rich.” In Asia, we share – or shared – this spirit of sufficiency, a sense that “enough is enough.” But Japan has lost much of this spirit during decades of high economic growth. We need to regain and rebuild this culture again.

If your country has important values, culture and mindsets among the people, please make an effort to retain and enhance them. Retaining is much easier and less costly than losing and regaining.

Editor’s Note: This article is reproduced in edited form with permission from Issue #143 of the Japan for Sustainability Newsletter. JFS is a non-profit communication platform to disseminate environmental information from Japan to the world with the aim of helping both move onto a sustainable path.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November/December 2014 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Author

-

Junko Edahiro

Japan For Sustainability

c/o e’s Inc.

Funabashi 1-11-12 Sanko Building 3F

Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 156-0055 Japan

Related Posts

Aquafeeds

Aquaculture feed composition helps define potential for water pollution

A study found that feed for salmon and trout had higher organic carbon concentrations than did catfish, shrimp and tilapia feeds. Nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations were similar among salmon, trout and shrimp feeds, and higher than those in catfish and tilapia feeds.

Intelligence

Aquaculture 2016: Examining the industry’s role in the food system

A wide range of important topics was discussed at the Aquaculture 2016 conference and trade show in Las Vegas last week. Editor Emeritus Darryl Jory shares his notes from the four-day event, which occurs every three years.

Innovation & Investment

Maine scallop farmers get the hang of Japanese technique

Thanks in part to a unique “sister state” relationship that Maine shares with Aomori Prefecture, a scallop farming technique and related equipment developed in Japan are headed to the United States. Using the equipment could save growers time and money and could signal the birth of a new industry.

Health & Welfare

Japanese eels: Progress in breeding and nutrition

The Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) is cultured in ponds in Japan, China, the Republic of Korea and other countries. Ongoing research is addressing knowledge gaps in the domestication, controlled breeding and nutritional requirements of the species.