Increasing demand will further drive new tilapia aquaculture business

Tilapia were first brought to Brazil in 1953, but only over the past decade has tilapia farming grown to commercial scale. Since 1999, the industry has expanded at an average annual growth rate of 18 percent. In 2009, the Brazilian Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture reported the tilapia harvest was 133,000 metric tons (MT).

Over the years, Brazilian farmers have used a number of tilapia strains, starting with the Florida red and more recently the genetically male tilapia. Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), Chitralada strain, brought from Thailand in 1995, has established itself as the main strain farmed in the country.

Much of the tilapia aquaculture takes place in floating cages near many of Brazil’s coastal areas.

Cage characteristics

Brazil holds about 10 million hectares of freshwater in dams, rivers, lakes and man-made reservoirs. Floating cages have become the most popular system for rearing tilapia in Brazil in areas with suitable water quality, flushing rates and water depth.

Tilapia cages are simple to build, inexpensive (U.S. $400 for a 6-cubic-meter cage) and easy to manage. Cages are usually constructed with rigid or flexible nets made from plastic-coated galvanized steel, stainless steel or synthetic fibers such as polypropylene. Steel nets are more widespread, as they better resist predatory fish such as the piranhas found in some inland areas in the country. Cage frames are made from stainless steel or galvanized steel. Strong, long-life, high-density polyethylene frames are less widely available and more costly, but have become the choice of farms that operate with medium-volume cages.

In sites close to shore, stationary cages are spaced 2 to 4 meters apart in groups and docked with anchoring poles fixed inshore. Otherwise, submerged chains and ropes attached to concrete bottom weights are used as mooring systems. To facilitate daily management, many farms now adopt walkways made from wood attached to empty barrels or plastic containers.

Most cages used for tilapia rearing have small volumes of 4 to 20 cubic meters. These can be round or square in shape with heights not greater than 2 meters. The cages can safely operate with high stocking densities (starting at 120 kg tilapia per cubic meter) due to rapid water exchange.

Since much of Brazil’s tilapia sales are domestic and retail, small-volume cages allow the harvest of fewer quantities of fish without imposing stress on the greater stocked population. As cages move beyond 10 cubic meters in volume with monthly harvests exceeding 10 MT, farms require a moderate level of capital investment and cash flow, and scale harvests for consistent sales and production flow.

Tilapia farms that operate with cages beyond 300 cubic meters in volume are sometimes vertically integrated from fingerling production to fish distribution. They operate with processing plants and sales contracts that require the harvest of large volumes of tilapia at a time.

In larger-volume cages, final stocking densities are reduced to 60 kg of fish per cubic meter. They have the disadvantage of poor flexibility and maneuverability, but on the other hand, can represent significant savings in labor force.

Nursery

Sex-reversed tilapia are usually sold to growout farms as fry with wet body weights between 0.2 and 0.5 grams. A thousand tilapia fry cost U.S. $30 to $45, depending on quality, location and availability. When available at short distances, some farmers prefer acquiring juvenile fish of 10- to 30-gram weight, although their prices may exceed $80/1,000 fish. At this stage, fish mortality can be significantly reduced and the grow-out cycle shortened.

Earthen ponds may be used for the nursery of Chitralada fry prior to stocking in cages. However, cages equipped internally with flexible 5-mm mesh nets are usually more common, as they facilitate fish handling and transfer to grow-out cages. In cages, it takes five to eight weeks to grow 0.5-gram fry to 30-gram juveniles, depending on stocking density, feed and water quality.

Size grading

Tilapia growth can vary widely within the same stock, especially when the fish are subjected to high density. This is in part due to genetic differences, but also because of competitive interactions among fish. Some fish outcompete others for feed and consequently grow faster. As a result, size grading becomes a major management component of tilapia cage farming.

When tilapia are transferred to different cages, it also allows moving the stock to clean units with larger mesh sizes, which promotes greater water exchange within the rearing unit. From 5-mm mesh sizes, 10-gram fish are usually moved to cages with mesh sizes of up to 15 mm. Then 30 to 200-gram tilapia are held within nets of 15- to 25-mm mesh. The mesh on nets for fish larger than 200 g is 25 mm or wider.

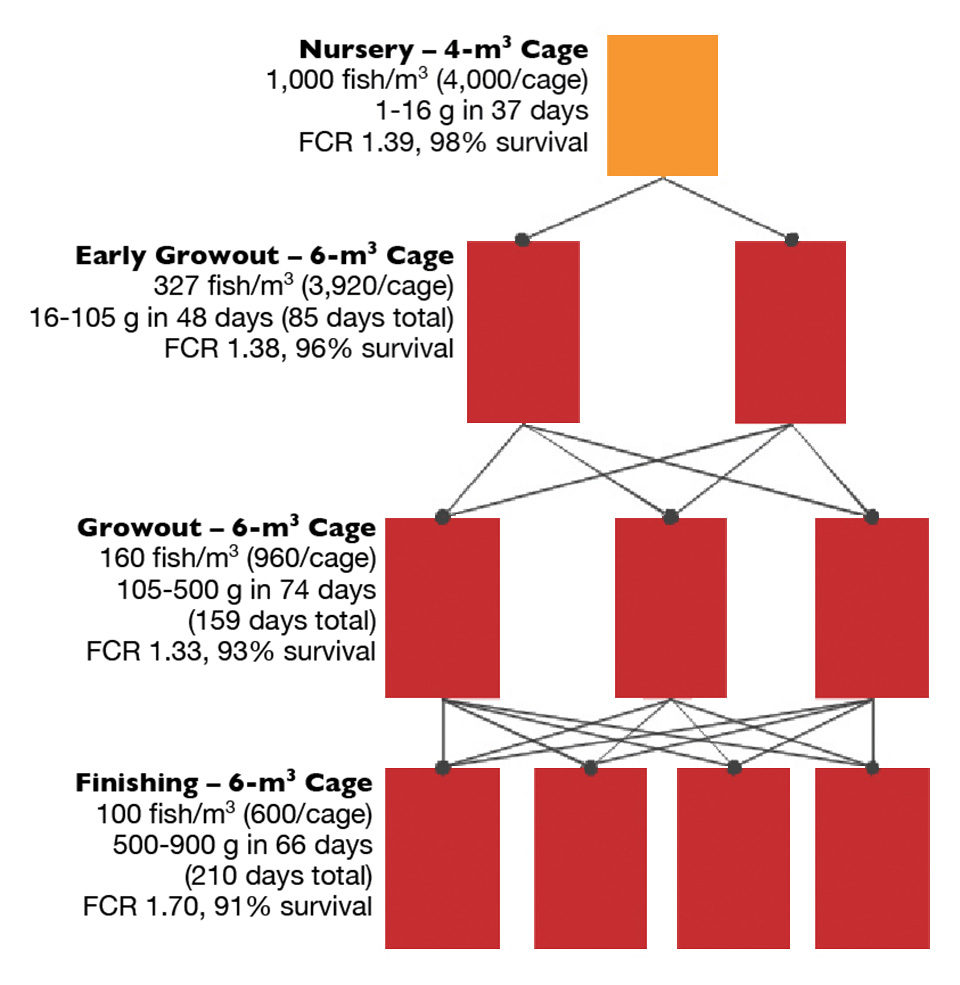

Grading frequency depends on a number of variables, including the targeted fish size at harvest, number of cages available on site, stock size variation, degree of prevalent stress and health status of the stocked population. Many farmers target tilapia above 900 g in weight to achieve premium prices. For this fish weight, grading can be carried out two to three times in a production cycle (Fig. 1).

During the rainy season, when fish become more susceptible to disease outbreaks, there is a reduction in tilapia stocking density as well as grading frequency. When size grading is adopted, final tilapia body weight variation can be reduced from 40 percent at initial stages to about 15 percent at harvest time. Tilapia are often sorted into four size categories, with the smallest, most challenged fish removed as early as possible since their delay in growth can not be recovered during the production cycle. Fish are usually sorted manually by eye, but in large operations, this procedure can be mechanized.

Feeds, feeding

Cage-farmed tilapia in Brazil receive only extruded diets. Feed protein content, pellet size and suggested feeding rates may vary according to the feed manufacturer. Fish feeds tend to be high in protein content at initial stages and drop as fish attain larger sizes (Table 1). Growout and finishing feeds are usually 32 percent in protein content and may represent up to 80 percent of all feeding costs at a cage farm. Feed costs to produce a 1-kg tilapia can range U.S. $1.10-1.30/kg of fish harvested. As such, feed management is critical to the economics of a cage operation.

Nunes, Feeding table for the rearing of tilapia, Table 1

| Fish Weight | Crude Protein | Particle Size | Feeding Rate* |

|---|

Fish Weight | Crude Protein | Particle Size | Feeding Rate* |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.1-5.0 g | 40-45% | < 1 mm | 10.0-18.0% |

| 5.0-30.0 g | 40-45% | 1-2 mm | 6.0-10.0% |

| 30.0-100.0 g | 35-40% | 2-4 mm | 3.0-6.0% |

| 100.0-200.0 g | 30-35% | 4-6 mm | 2.5-3.0% |

| 200.0-500.0 g | 30-32% | 6-8 mm | 2.0-2.5% |

| 500.0 g-1.2 kg | 28-32% | 6-8 mm | 1.5-2.0% |

To determine maximum ration sizes, farmers usually follow suggested rates from commercial feeding tables. However, rations are adjusted on a daily basis depending on fish appetite. In small-volume cages, rations are never delivered in full amounts. Initially, fish can be fed only half of the calculated ration. The remainder is offered if the first ration is fully consumed within 30 minutes after distribution. After this period, uneaten feed can be oversaturated with water, and the heavier pellets exit the confined feed area, leading to feed loss.

Cage operations equipped with walkways allow more detailed inspections of feed consumption. They facilitate feed handling and storage, and promote feed delivery to as often as 8 times/day during grow-out – compared to three times when distributed from feed boats. Walkways also allow the collection of fish debris and more frequent clean-up of feeding rings or net curtains.

Perspectives

Tilapia cage farming will continue to grow quickly in the years to come in Brazil to reduce the increasing domestic deficit of fisheries products in the country. Tilapia are mostly marketed fresh and degutted at weights of 700 to 900 grams. Farm gate prices range U.S. $2.00-2.80/kg.

Today a great proportion of Brazil’s tilapia production is consumed in the countryside, but the fish are also now found in large supermarket chains, restaurants and fish markets all over the country. As capture fisheries continue to decline in Brazil and more city residents learn to appreciate tilapia, increasing demand will further drive new entrepreneurs into tilapia aquaculture. In this new scenario, medium-size cages and more mechanized practices will emerge to keep pace with large-scale production and more-efficient operations.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November/December 2010 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Alberto J.P. Nunes, Ph.D.

Instituto de Ciências do Mar – Labomar

Av. da Abolição, 3207 – Meireles

Fortaleza, Ceará, 60.165-081 Brazil

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

10 paths to low productivity and profitability with tilapia in sub-Saharan Africa

Tilapia culture in sub-Saharan Africa suffers from low productivity and profitability. A comprehensive management approach is needed to address the root causes.

Health & Welfare

A look at tilapia aquaculture in Ghana

Aquaculture in Ghana has overcome its historic fits and starts and is helping to narrow the gap between domestic seafood production and consumption. Production is based on Nile tilapia.

Responsibility

Addressing safety in Latin America’s tilapia supply chain

Over the last decade, the experience gained by many tilapia farmers combined with proficient programs implemented by local governments have significantly improved tilapia production in various Latin American countries like Colombia, Mexico, Ecuador and other important tilapia producers in the region.

Health & Welfare

Advice for managing predatory birds, part 1

Predatory birds can cause major losses for tilapia farms. As some bird species are protected by law, fish farmers must use non-lethal control techniques.