London event designed for investors addresses numerous issues like aquafeeds, emerging technologies and defining the ‘smallholder’

Innovation in genetics, farm management, animal welfare and more has made the seafood industry increasingly investable over the past decade, with aquaculture services and technologies emerging as particularly attractive startups. Investment is what is making those great new ideas bigger, better and more likely to stick around.

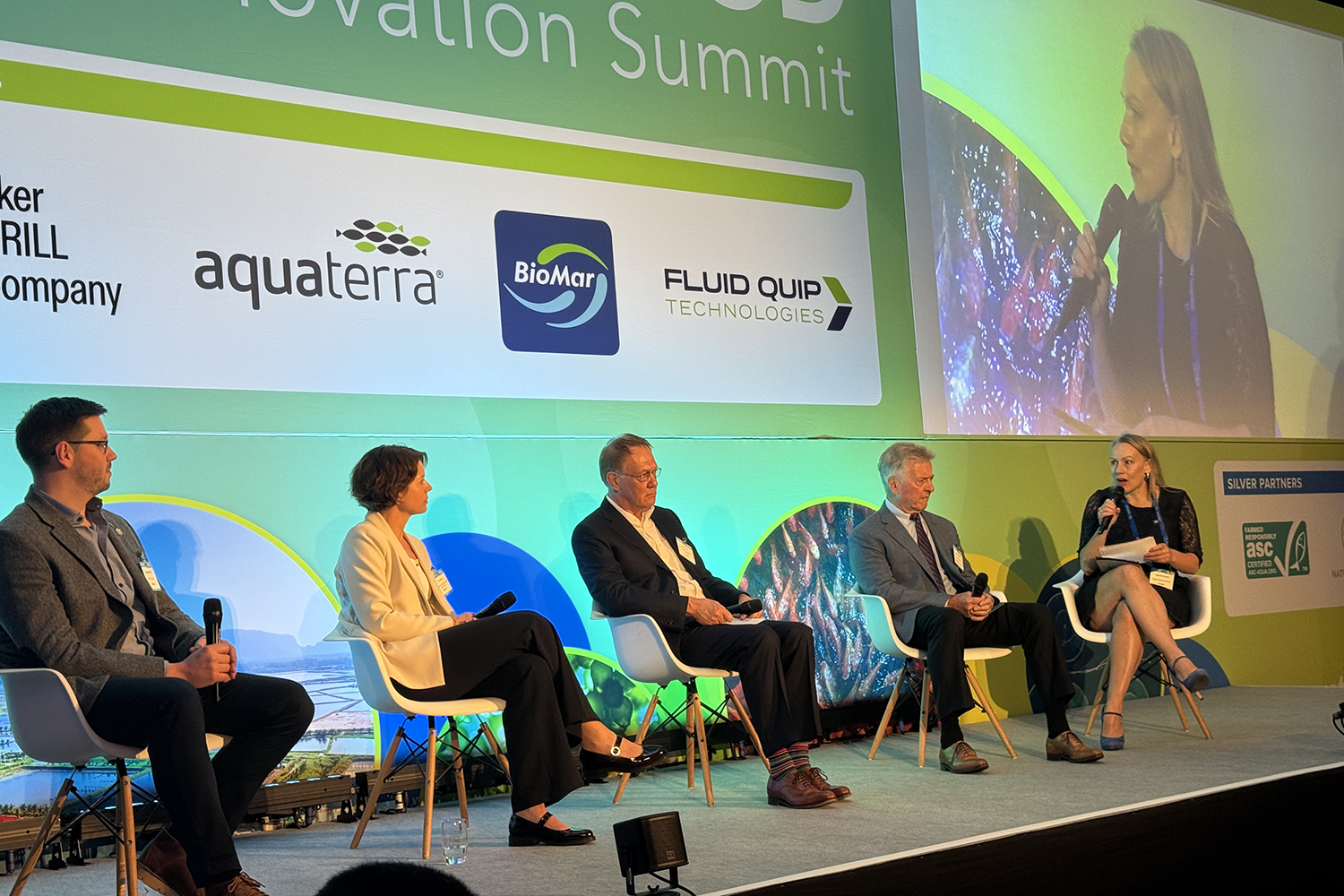

At this year’s Blue Food Innovation Summit in London, the massive capital needs of a still-evolving “blue food” or aquatic-foods industry were laid out for prospective investors. It’s become clear to them that seafood investments come with plenty of risk, require an unusually patient outlook and that even successful sectors in the business face uncertain futures.

Take the world-leading global farmed salmon sector for example: Far more advanced than any other fish-farming sector yet constricted by regulations and geography and beset with social license challenges that past mistakes have amplified.

“Global salmon production, 80 percent of it is in two countries [Norway and Chile]. And salmon production growth has been very limited in the last four or five years,” said Steven Rafferty, CEO of Cermaq Global. “It’s growing more this year, but we have struggled as an industry to really expand. And part of the issue is climate change, higher water temperatures, etc. And salmon are not able to grow in many parts of the world. In fact, most of the [top producing] countries today are the same as they were 20 years ago, with maybe the exception of Iceland.”

Salmon aquaculture, particularly in Norway, benefits from massive investments from the private sector, government and academia. With a high-value product and good sales margins historically, investment has continued, Rafferty noted. But with limited space and uncertain environments in which to farm, growth prospects will require innovative thinking in terms of farm technology, site planning on land and further infrastructure improvements, all of which come at a cost.

“These are extremely expensive, so it’s taking time to scale up, and that’s really why we’ve not seen too much development,” added Rafferty. And the rest of the aquaculture world is waiting, he noted, because Norway sees its knowledge and technology advancing from the “fjords of Norway to the global South” and other fish-farming sectors.

Catarina Martins, chief technology and sustainability officer at Mowi, the world’s largest salmon farming company, agreed that it’s Norway’s role to upscale and economize aquaculture technology for the rest of the world’s benefit. “There’s a lot we can do with the current technology we have, but [we need to bring] it to the next level that we actually call ‘smart farming’ with underwater technologies, sensors, allowing us to understand at the higher, granular level what is happening in the sea so that we can start taking much more proactive decisions, which will help make production more efficient.”

Getting into specifics about such decisions, Martins pointed out that stocking larger smolts in the ocean environment has become a winning strategy that derisks the farming process by reducing the fish’s exposure, limiting mortalities and by controlling feed costs. By using recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) for young fish, Mowi is now stocking fish that weigh 700 grams to 1 kilogram, whereas in the past they might put 500-gram fish in net pens.

“We have data indicating that we are able to reduce mortality rates by 50 percent and that we are able to have 200 fewer days of production time at sea. All of those will help us with our sustainability job,” Martins said.

Blue collar investment

Aquaculture investment is more than businesspeople in suits speaking in London hotel conferences – it’s the energy, time and money that farmers themselves put into their livelihoods. Chris Ninnes, CEO of the Aquaculture Stewardship Council, said that producers’ needs should be looked after. Aquaculture insurance and formal credit will benefit small-scale fish producers, which make up the bulk of the industry in areas of the world like Southeast Asia, he said. De-risking the investments that farmers make is “urgently needed” in the aquaculture sector, he added, and that new approaches to growing responsible practices are needed in Asia.

“In 2030, we estimate that just under one-quarter [of global aquaculture production] will actually be going into markets demanding sustainability,” said Ninnes. Working with retailers to drive better performance on the waters has been the “main incentive pathway” for certification groups like ASC, he said, but new modes of thinking are needed where most of the world’s fish is actually produced. “That’s a big, big challenge,” he said.

The challenges to expanding aquaculture financial services are not limited to Asia. Lorella de la Cruz Inglesias, directorate general for maritime affairs and fisheries at the European Commission, said that even though EU member states recognize the need to support and grow the aquaculture sector for many different reasons, including food security, jobs and livelihoods in rural communities, “it’s not happening,” she said.

“There was a strategy that was adopted in 2021 by the Commission, identifying all the different obstacles to the growth of aquaculture in the EU,” de la Cruz Inglesias said. “And we are currently implementing this strategy with member states because, in fact, in terms of governance in the EU, most of the governance happens at member states level, it’s not the EU.”

‘The biggest company in aquaculture’

Space and acceptance are not the only limiting factors for global aquaculture: Feed is another. With flat wild-capture production for decades, feed manufacturers must engage with a wide range of ingredient providers – marine, terrestrial, insects, algae and single-cell proteins – to meet the demand of today’s producers. If the industry were to expand, more feed ingredients would be necessary.

Peter Williams, senior nutritionist at Fluid Quip Technologies and emeritus professor at the University of Nottingham Trent, said that 70 percent of the protein that EU producers use in their feeds is imported. For “sovereignty of protein,” Williams urged a reversal of that trend and pointed to the fermentation of dried distillers’ grains, which creates “a tremendous amount of yeast” that can be used to manufacture a highly digestible protein for animals.

“There’s about 15,000 tons of yeast produced in the fermentation process in the European dry-grind ethanol facilities, so let’s capture that and make it into a very high-value protein source,” which Fluid Quip is doing. “It was technology added to a traditional process that made this tremendous leap. Now, the issue is brought up this morning, it’s the cost of doing that.”

Alan Shaw, CEO of Calysta, spoke about the power of fermentation and how it plays into the process of creating FeedKind, a feed ingredient made from a single-cell protein that is 70 to 72 percent protein, using one of the cheapest forms of carbon on the plant, CH4 methane.

“The value creation is 10X. We produce 500 kilograms of protein an hour, which is equivalent to the edible protein of 10 cows,” said Shaw. “So in terms of sustainability from a protein production perspective, we’re probably the biggest company in the world. And we’re certainly the biggest company in aquaculture.”

Calysta’s massive plant in Chongqing, China, required more than $100 million to build and the company has raised more than $850 in external and internal investment. “If you build a plant like that, you want to get a return,” said Shaw, urging that speed is as important as scale in the eyes of global investors.

“Our plant is in China and our target customer base are shrimp farmers and 75 percent of shrimp farmers don’t give a damn about sustainability. The only thing they care about is price and cost. Now our product has a secret and its secret is linked to the fact that it’s a microbial product. So it has a massive positive impact on the immune system of every animal that eats it,” said Shaw, adding that the pet-food sector is adopting the product faster than aquaculture.

Shaw said that FeedKind proved effective in helping to safeguard shrimp from common diseases, but farmers are highly conservative and “all they want to do is buy protein,” he said.

Defining ‘small’

Global aquaculture has its giants like Norway’s Mowi and Calysta in China. But the industry is dominated by small-scale producers. Termed as “smallholders,” such producers are typically limited to one or two ponds covering about a hectare. Panelists participating in the discussion “Empower Smallholder Farmers: Innovative Solutions Increasing Efficiency and Reducing Financial Risk,” agreed that without a universal definition of a smallholder, it’s challenging to talk about how to meet their needs but their importance in the overall supply picture cannot be overstated.

Liris Maduningtyas, CEO of Jala Tech, which provides smart-farming services to shrimp producers in Indonesia, said her company delineates “small-scale” from “large-scale” producers based on their stocking density, the number of ponds in production, the total area and the level of productivity (less than 5 metric tons per hectare per production cycle is the demarcation line).

Joseph Rehman, founder and group CEO for Victory Group, a fish farmer in Kenya, said they work with “pond partners,” small-scale producers who contribute to the overall output of the “core nucleus farm.” Rehman said there’s a “bit of baggage” associated with the term smallholder, folks with 1 or 2 acres. But developing this network helped the company overcome a limiting factor with its hatchery.

“We set that up and now we’ve got dozens of partners. It’s actually 100 in total who are involved with the whole system,” said Rehman, adding that the doubling of size meant an additional 10,000 tons of fish for Victory. “And last year we doubled in size as a company completely through eggs produced by our community or produced by our client partners. So in that sense, the efficiency of it, it’s interesting to think about what the efficiency of a smallholder actually means. If we measure it by the volume of eggs, it’s not a useful metric because [that data] didn’t exist five years ago. If we measure it by profit per partner, it’s been astronomical.”

Another cool development for Victory is the use of drones to transport eggs, which reduces the transport time significantly in rural areas of Kenya where the roads can be unreliable.

Maduningtyas said that smallholders in Indonesia can be challenging to work with on various fronts, including the fact that shrimp farming is often part of a “mixed livelihood.”

“We have to look at [them] very differently. The hardest challenge when we deal with small-scale farmers is to deal with their mentality,” she said, adding that larger farming operations are often more willing and ready to invest in technology solutions like those offered by Jala.

Nicholas Hill, co-founder and CEO of Coast 4C, which connects investors to coastal agriculture and regenerative seaweed farming, said that working with smallholders require a “huge range of skill sets.”

“You’ve got to organize people and you’ve got to drive behavior change,” he said. “And a lot of the time, a lot of what we’re actually doing is behavior change, whether that’s the adoption of technology or anything else.”

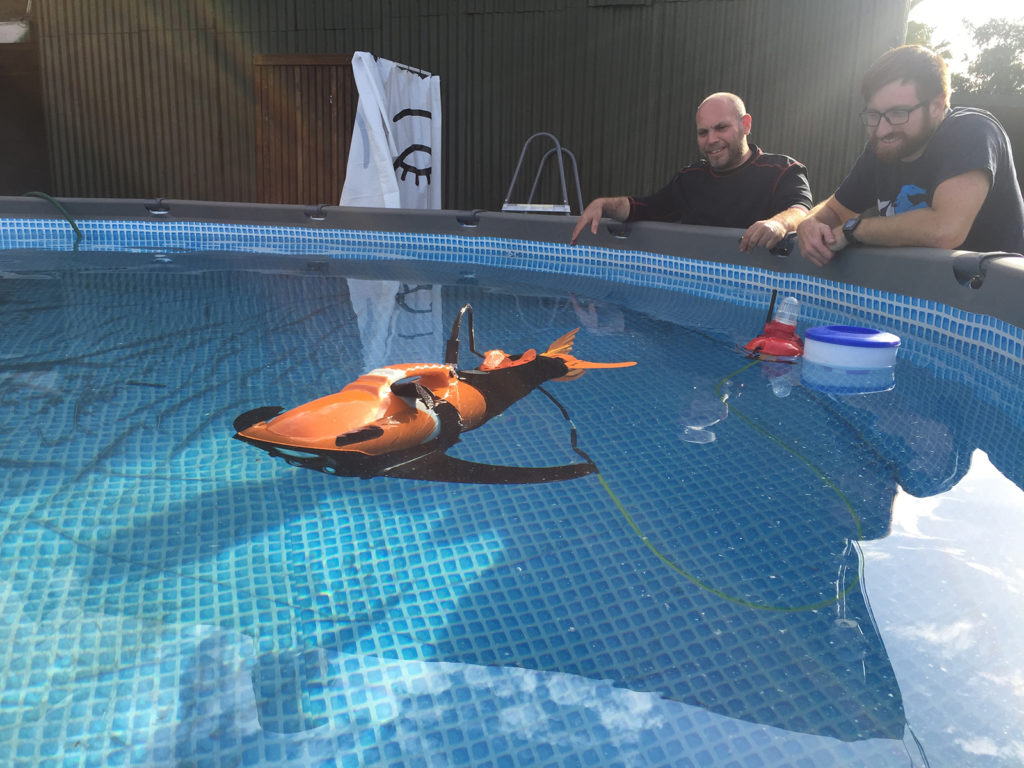

‘This job is not for a person’: Underwater robots take on tough tasks in aquaculture

Elephant in the room

The conference, designed to attract investors to the blue food sector, was held just months after one of the most hyped aquaculture technology startups, the automated feeder company e-Fishery, was exposed for massive accounting fraud, costing investors around the world hundreds of millions of dollars. Maria Velkova, chief portfolio officer at Aqua-Spark, the Netherlands-based investment firm that was an early investor in e-Fishery, addressed the issue.

Velkova said the incident was “very, very unfortunate” and “emotional” for the Aqua-Spark team because “I think we were all looking up to a success” that the sector needed. “I think we are much more resilient than just thinking that one company that failed is going to have a massive impact.”

Citing failures in other industries like technology, energy and finance, Velkova said the failure should not discourage investors from approaching the blue food sector.

“In general, look at the financial sector. If you talk to someone coming from the financial sector they wouldn’t even raise an eyebrow,” said Velkova. “I’m saying this with a lot of sadness because I don’t want this to be the normal, but at the same time it does happen. It was such a great thing for the industry. The momentum that came from it was felt by other deals. And the innovation was still a valid, good innovation in the field.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

Tagged With

Related Posts

Aquafeeds

Aqua-Spark invests in Finnish biotech startup to scale up fungal protein production

Funding enables eniferBio to scale up production of PEKILO® fungal protein powder and seek approval from the EU and other markets.

Innovation & Investment

GOAL 2016 preview: IPA technology catching on in China

Intensive pond aquaculture (IPA) technology, a floating, in-pond raceway system developed in the United States, is being adopted fast in China, just three years after its introduction, says Jim Zhang, aquaculture program manager for USSEC-China.

Innovation & Investment

Exit stage right: Fish 2.0 offers final set of winning innovators

Nearly 40 entrepreneurs took the stage to pitch their seafood industry-changing innovations in front of a room full of discriminating investors.

Innovation & Investment

Fish farmers turn to drones for health, feed monitoring

Two technology startups are offering unique fish-monitoring solutions for aquaculture producers. Using algorithms, drones and computer vision software, Aquaai and Aquabyte aim to take labor-intensive and error-prone tasks out of human hands.