Findings from first assessment of marine heat waves deep underwater may have ‘important implications’ for commercial fisheries management

New research led by NOAA scientists shows that marine heat waves happen deep underwater. The study, which was published Nature Communications, used a combination of observations and computer models to generate the first broad assessment of bottom marine heat waves in the productive continental shelf waters surrounding North America.

“Researchers have been investigating marine heat waves at the sea surface for over a decade now,” said Dillon Amaya, lead author and a research scientist with NOAA’s Physical Science Laboratory. “This is the first time we’ve been able to really dive deeper and assess how these extreme events unfold along shallow seafloors.”

Most research on marine heat waves has focused on temperature extremes at the ocean’s surface, for which there are many more high-quality observations taken by satellites, ships and buoys. Sea surface temperatures can also be indicators for many physical and biochemical ocean characteristics of sensitive marine ecosystems, making analyses more straightforward.

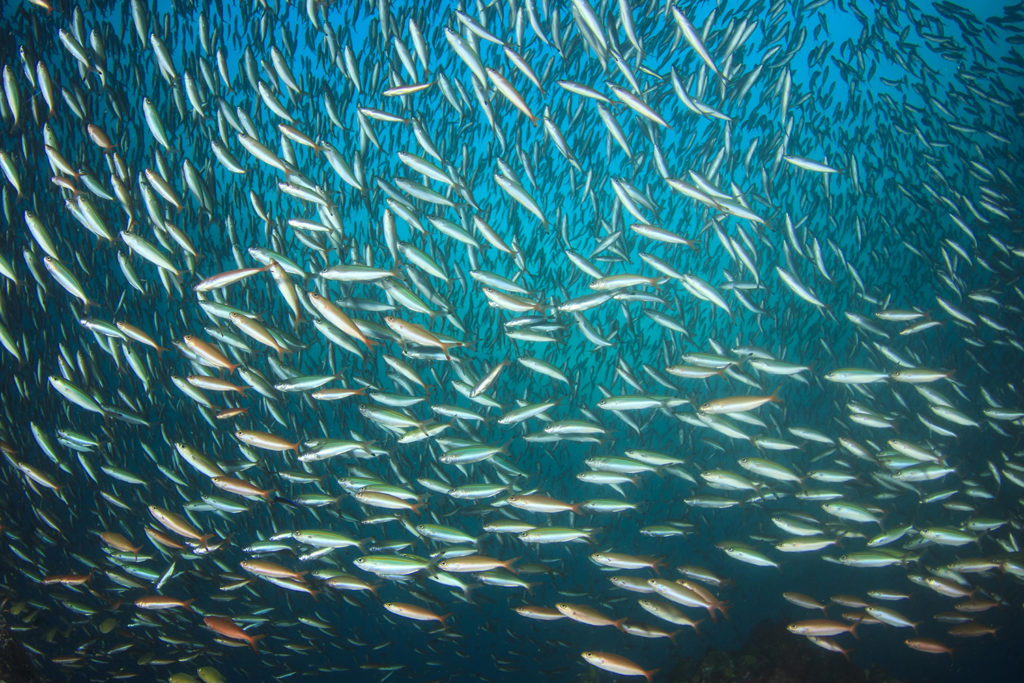

In recent years, scientists have increased efforts to investigate marine heat waves throughout the water column using the limited data available. But previous research didn’t target temperature extremes on the ocean bottom along continental shelves, which provide critical habitat for important commercial species like lobsters, scallops, crabs, flounder, cod and other groundfish.

Due to the relative scarcity of bottom-water temperature datasets, the scientists used a data product called “reanalysis” to conduct the assessment, which starts with available observations and employs computer models that simulate ocean currents and the influence of the atmosphere to “fill in the blanks.” Using a similar technique, NOAA scientists have been able to reconstruct global weather back to the early 19th century.

While ocean reanalyses have been around for a long time, they have only recently become skillful enough and have high enough resolution to examine ocean features, including bottom temperatures, near the coast.

Gaps in the conservation status of the most important fished species of marine fish

The research team found that on the continental shelves around North America, bottom marine heat waves tend to persist longer than their surface counterparts and can have larger warming signals than the overlying surface waters. Bottom and surface marine heat waves can occur simultaneously in the same location, especially in shallower regions where surface and bottom waters mingle.

But bottom marine heat waves can also occur with little or no evidence of warming at the surface, which has important implications for the management of commercially important fisheries.

“That means it can be happening without managers realizing it until the impacts start to show,” said Amaya.

In 2015, a combination of harmful algal blooms and loss of kelp forest habitat off the West Coast of the United States led to closures of shellfisheries that cost the economy in excess of $185 million, according to a 2021 study. The commercial tri-state Dungeness crab fishery recorded a loss of $97.5 million, affecting both tribal and nontribal fisheries. Washington and Californian coastal communities lost a combined $84 million in tourist spending due to the closure of recreational razor clam and abalone fisheries.

Unusually warm bottom water temperatures have also been linked to the expansion of invasive lionfish along the southeast U.S., coral bleaching and subsequent declines of reef fish, changes in survival rates of young Atlantic cod and the disappearance of near-shore lobster populations in southern New England.

The authors say it will be important to maintain existing continental shelf monitoring systems and to develop new real-time monitoring capabilities to alert marine resource managers to bottom warming conditions.

“We know that early recognition of marine heat waves is needed for proactive management of the coastal ocean,” said co-author Michael Jacox, a research oceanographer who splits his time between NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center and the Physical Sciences Laboratory. “Now it’s clear that we need to pay closer attention to the ocean bottom, where some of the most valuable species live and can experience heat waves quite different from those on the surface.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

Related Posts

Responsibility

Hottest ocean temperature record set in 2022 for seventh consecutive year

Research says a record-high ocean temperature combined with greater salinity could create inhospitable ocean conditions for marine life.

Responsibility

2021 heat wave created ‘perfect storm’ for shellfish die-off

Researchers have produced the first comprehensive report detailing the impacts of the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat wave on shellfish.

Fisheries

Increasingly frequent and costly, marine heatwaves are testing the resilience of fisheries and aquaculture

Marine heatwaves have already caused severe losses for seafood, but in some cases, the industry may see some benefits from these events.

Responsibility

Study: Climate change will shuffle marine ecosystems in unexpected ways as ocean temperature warms

A study found that, as the ocean temperature warms, fish will continue to exist in certain areas but are not likely to be as abundant.