Small-scale fisheries make big contributions to the global nutrient supply

Unhealthy diets and insufficient food are the leading cause of death globally, with more than 2 billion people considered food insecure. Concurrently, more than 3.3 billion people around the world depend on fish for at least 20 percent of their animal protein intake and in many developing countries, seafood accounts for more than 50 percent of the total animal protein intake.

In addition to protein, seafood provides critical contributions of nutrients such as iron, zinc, calcium, iodine, selenium, vitamin B12 and fatty acids. The human body needs consistent access to small quantities of these micronutrients to enable proper physiological and immune function. Beyond their role in filling micronutrient gaps in nutritionally vulnerable communities, seafood can displace the consumption of less healthy meats, and two servings per week can significantly reduce the risk of certain non-communicable diseases and prenatal and child mortality, thus increasing life expectancy and quality.

Small-scale fisheries (SSFs) can be broadly defined as fishing activities occurring on smaller boats or on foot, for commercial and/or subsistence purposes, yet there is still no consensus among countries on where to draw the line between small-scale and industrial fisheries. Catch from the small-scale fisheries sector can contribute to human nutrition through two main pathways: direct seafood consumption and fisheries-derived income that is redirected toward purchases that improve nutrition.

Seafood sold within communities or at local markets can be more affordable than other animal proteins such as beef or chicken, providing an important nutrient source for coastal communities that do not have access to broader food markets. Seafood sales are also an important source of income for fishers and other actors along the supply chain, which can have positive effects on a household’s food purchasing power. In addition, SSFs provide a food source with low carbon and environmental footprint compared to other terrestrial animal-sourced foods, thus contributing to the sustainability of coastal communities and the planet.

This article – summarized from the original publication (Viana, D.F. et al. 2023. Nutrient supply from marine small-scale fisheries. Sci Rep 13, 11357 (2023)) – reports on a study that analyzed the relative contributions of marine SSFs to nutrient supply at national levels relative to: (1) all other seafood producing sectors, (2) all other animal-sourced foods, and (3) all other foods. It also calculated the contribution of SSFs to national nutrient supplies in relation to estimates of inadequate nutrient intakes, allowing for the classification of importance and vulnerability to shocks in SSFs production.

Study setup

In our study, we considered catch from small-scale fisheries as the catch from artisanal and subsistence sectors defined by the Sea Around Us project, which is the data used in the analysis.

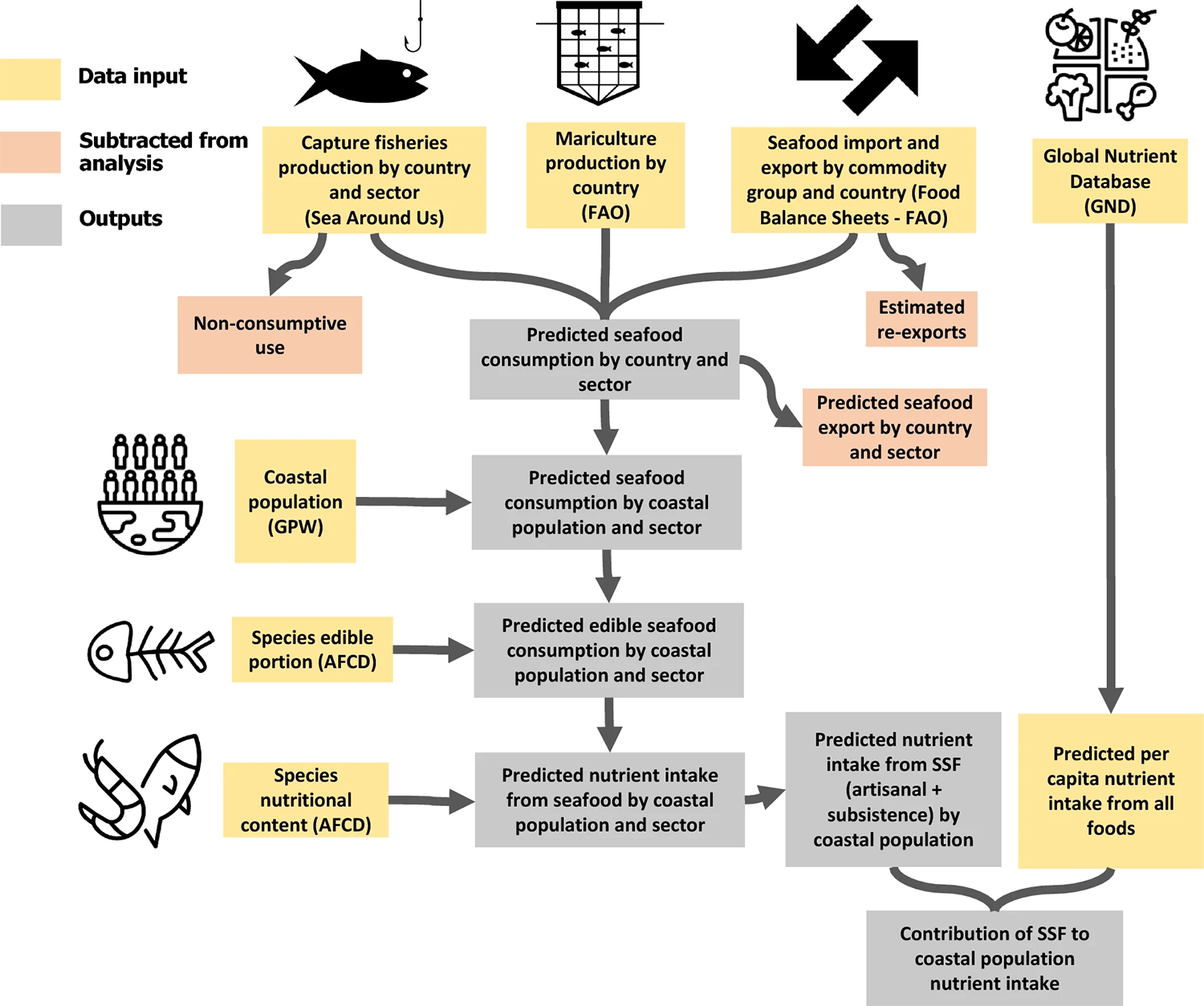

Global studies that focused on small-scale fisheries have highlighted their importance for food security but did not focus on nutrient supply for coastal communities. To address this knowledge gap, we combined information on global catch, aquaculture production and seafood trade, nutrient composition of aquatic species (AFCD), and global nutrient supply (GND) and assessed the relative importance of marine small-scale fisheries to the supply of zinc, iron, protein, vitamin B12, omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (hereafter referred as DHA + EPA) and calcium.

For detailed information on the study setup, and data collection and analyses, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

Despite increased global attention to the potential role of fisheries in food security and human nutrition, no study has estimated the contribution of small-scale fisheries to nutrient supply on a global scale. Past global studies have focused on the importance of capture fisheries and aquaculture to human nutrition but haven’t focused specifically on small-scale fisheries.

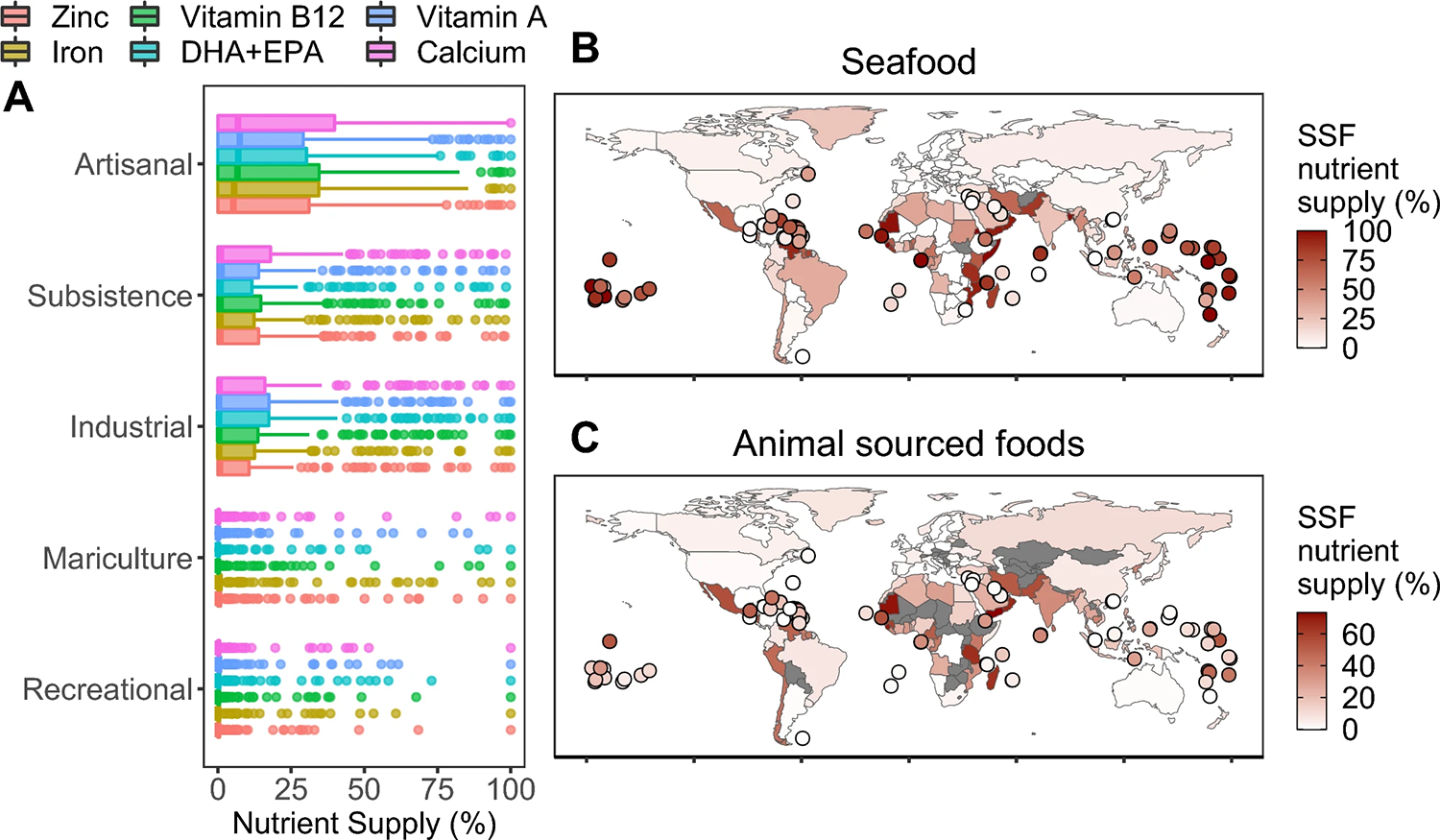

We estimated the relative contribution each seafood-producing sector to total national aquatic food nutrient supply. On average, small-scale (artisanal and subsistence) and industrial fisheries had the highest relative contribution to nutrient supply followed by mariculture and recreational fisheries. Even though imported seafood was produced by both aquaculture and capture fisheries, we treated it separately because of data limitations. Therefore, nutrient supply by sector are estimates of the seafood produced and retained within each country and does not account for imported seafood from mariculture or capture fisheries. Consequently, national contribution of the different sectors can be underestimated in countries that import large quantities of seafood.

Our global analysis shows that small-scale fisheries are an important source of key nutrients for vulnerable coastal populations. We compared national-level estimates of nutrient supply from SSFs to the overall average nutrient supply of all foods consumed within each country (e.g., grains, fruits, dairy, other animal foods), based on the Global Nutrient Database.

We estimated that about one-quarter of coastal nations around the world rely on small-scale fisheries for more than 15 percent of mean nutrient intake across assessed nutrients (iron, zinc, calcium, DHA + EPA and vitamins A and B12). When considering nutritionally vulnerable countries (defined as a mean national prevalence of inadequate intake over 50 percent), about half of coastal nations rely on SSFs catch for at least 15 percent of nutrient supply. However, more than 20 nations across Africa, Pacific, Asia and the Caribbean, obtain more than 30 percent of their nutrient supply from small-scale fisheries catch. In such countries, any decline in availability and/or access to seafood can have significant negative consequences to health and nutrition of the population.

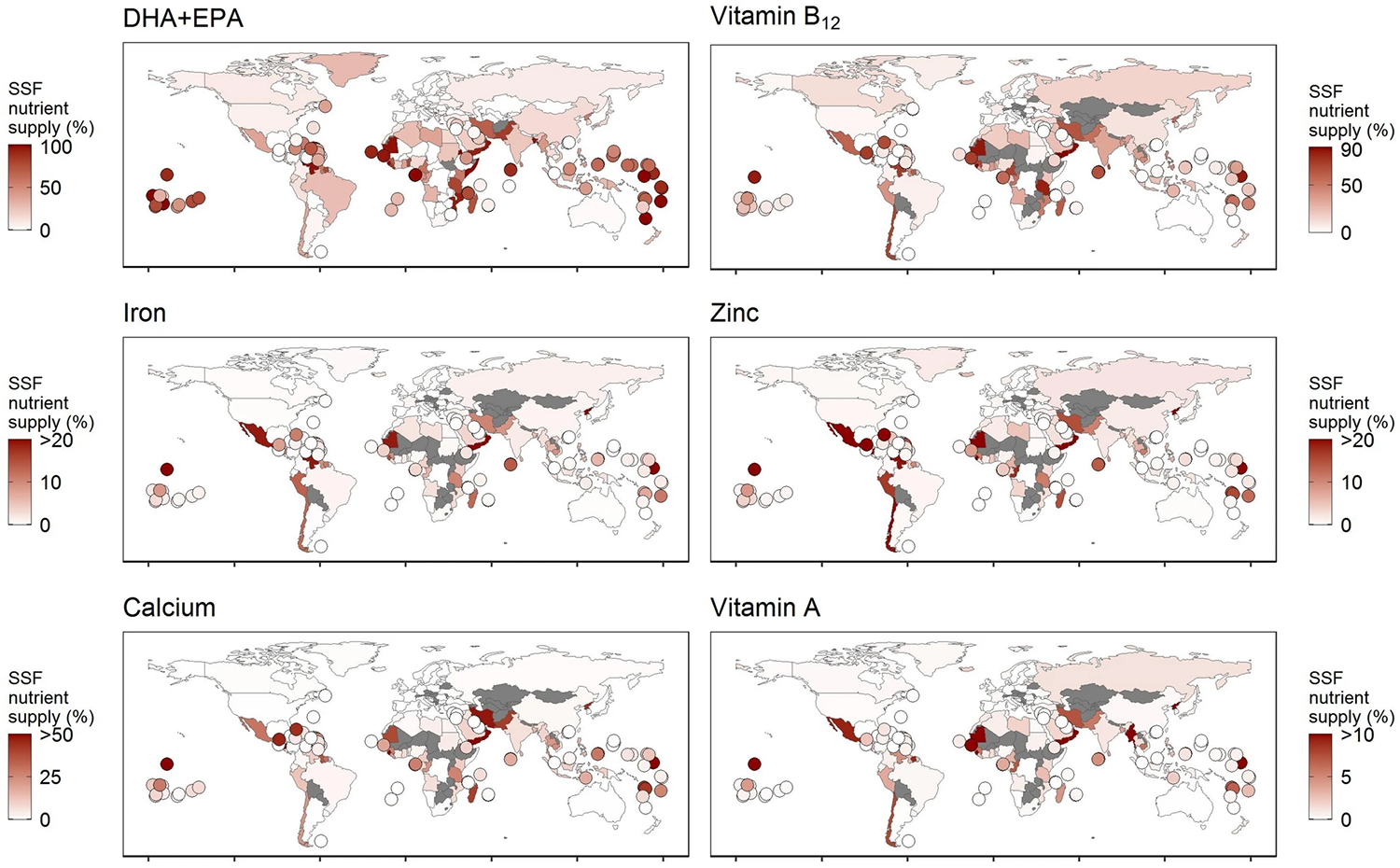

On average, we found that SSFs contribute about 10 percent of the total nutrient supply of coastal populations. More specifically, SSFs supply, on average, including all countries, approximately 30 percent (0–100 percent) of DHA + EPA, 20 percent (0–90 percent) of vitamin B12, 9 percent (0–80 percent) of calcium, 5 percent (0–59 percent) of zinc, 3 percent (0–44 percent) of iron, and 2 percent (0–33 percent) of vitamin A to overall nutrient supplies. Yet, these averages belie the local nutritional importance of SSFs in some national contexts.

Small-scale fisheries catch is particularly important in populations that do not have access to diverse and rich diets. In many coastal areas around the globe, communities have access to staple foods (such as rice, wheat, corn, cassava) and aquatic foods serve as the sole form of animal-sourced food. In many diets, nutrients from SSFs – such as DHA + EPA fatty acids and vitamin B12 – are especially important for public health. Importantly, intake of DHA + EPA is associated with reduced risk of heart disease, and intake of vitamin B12 is associated with reduced risk of heart disease and cognitive decline. Here, we show that small-scale fisheries have particularly high contribution to the supply of vitamin B12, calcium and DHA + EPA, although it can also be important for other nutrients depending on the nutritional value of the species consumed and availability of other foods.

There are many reasons to believe our findings are a conservative estimate of the contribution of small-scale fisheries to human nutrition. First, we assumed that coastal populations have the same national average intake of other food types (including other animal-sourced foods) based on the GND database. However, in coastal communities, fish can often be the only source of animal-sourced foods, and other food types are not accessible.

Second, to calculate per capita consumption, we assumed that the entire coastal population within each country is consuming the small-scale fisheries catch. However, a large proportion of the catch can be sold in local markets around fishing communities. Many people living in larger cities along the coast might not consume small-scale fisheries catch and coastal communities might have higher than average seafood consumption. Therefore, average values presented in our results do not capture temporal and spatial variability in small-scale fisheries catch consumption across coastal populations.

Are aquaculture and fisheries resilient enough to withstand climate change?

Third, even though the Sea Around Us database accounts for unreported catch, a portion of the small-scale fisheries production could still be unreported. Fisheries that are destined for local consumption are particularly difficult to obtain production information and therefore can have higher levels of unreported catch. Fourth, because of data limitations, we considered consumption of muscle tissue only (excluding bones, skin, etc.), which can be commonly consumed in some cultures. Lastly, we conservatively considered that artisanal catch is part of the international seafood trade. However, in many countries the artisanal catch is destined to the local markets, with only very few highly valuable species being exported. Better data on these topics will increase the accuracy of the results presented here.

It is critical to understand whether SSFs production is stable over time or potentially declining due to overfishing, climate change, pollution, habitat degradation and loss, or other threats that could have negative impacts on human nutrition. Nutritionally vulnerable coastal populations that depend on SSFs and are particularly susceptible to fluctuations in catch and can benefit from sustained or increased catch through better resource management.

Successful examples of small-scale fisheries governance demonstrate the value of securing fishing rights and empowering local communities. Strategies that grant fishing rights to local communities (such as sustainable-use Marine Protected Areas, Territorial Use Rights for Fisheries, Locally Managed Marine Areas) incentivize management and promote sustainable practices, and thus can promote human health through nutrition.

The Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries, developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, recognizes the importance of securing tenure rights to achieve fisheries sustainability. Such principles are drawn from practical experiences of small-scale fisheries governance from around the world and can be adopted by nutritionally sensitive countries that depend on small-scale fisheries for nutrition.

Perspectives

In addition to improved management, policies supporting access to nutrient-rich fish could have a positive impact on diets where undernutrition is prevalent. Aquatic foods are one of the most widely traded food products in the world, moving nutritious food from nutritionally vulnerable to nutrient-secure nations. Although most SSF catch is consumed locally, policies prioritizing local consumption and targeted to specific nutritional needs can help address inadequate nutrient intake and improve food security.

Infrastructure and technological improvements that reduce food waste, improve food quality and safety and help cope with inter-annual variation or declines can also play an important role in improving human health in regions where nutrients are most needed. This is particularly true in countries with nutritionally vulnerable populations with high dependence on small-scale fisheries.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Daniel F. Viana, Ph.D.

Corresponding author

Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, 02115, USA

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

20,000 lettuces under the sea: Could underwater agriculture be the future of farming?

Preliminary research suggests that emerging mariculture methods could provide alternatives to land-based agriculture and within recirculating systems.

Responsibility

Eat the whole fish: A discussion of culture, economics and food waste solutions

The Big Fish Series explored the logistical and cultural challenges in front of greater whole-fish consumption and how much seafood is being wasted.

Aquafeeds

Counterpoint: Marine ingredients are stable in volume, strategic in aquaculture nutrition

IFFO Director General Petter M. Johannessen says fishmeal and fish oil offer unmatched nutrition and benefits to fuel aquaculture’s growth trajectory.

Intelligence

Analysis of global diets highlights persistent undernutrition

Climate change, shifting incomes and evolving diets complicate the search for solutions to obesity and undernutrition in vulnerable populations.