Biodegradable film includes with chitosan from crustaceans

Researchers have developed a biodegradable film made of a compound derived from limonene, the main component of citrus fruit peel, and chitosan, a biopolymer derived from the chitin present in exoskeletons of crustaceans.

Indiscriminate use of packaging materials derived from petroleum has led to a huge buildup of plastic in oceans and landfills, as these materials have low degradability and are not significantly recycled. To mitigate this problem and meet the growing demand for products that are safe for human health and the environment, the food industry is investing in the development of more sustainable packaging alternatives that preserve nutritional quality as well as organoleptic traits such as color, taste, smell and texture.

The film was developed by a research group in São Paulo state, Brazil, comprising scientists in the Department of Materials Engineering and Bioprocesses at the State University of Campinas’s School of Chemical Engineering (FEQ-UNICAMP) and the Packaging Technology Center at the Institute of Food Technology (ITAL) of the São Paulo State Department of Agriculture and Supply, also in Campinas.

“We focused on limonene because Brazil is one of the world’s largest producers of oranges (if not the largest) and São Paulo is the leading orange-producing state,” said Roniérik Pioli Vieira, co-author of the article and a professor at FEQ-UNICAMP.

Limonene has been used before in film for food packaging to enhance conservation thanks to its antioxidant and anti-microbial action, but its performance is impaired by volatility and instability during the packaging manufacturing process, even on a laboratory scale.

This is one of the obstacles to the use of bioactive compounds in commercial packaging. It’s often produced in processes that involve high temperatures and high shear rates due to cutting or shaping. Bioactive additives easily degrade in these processes.

“To solve this problem, we came up with the idea of using a derivative of limonene called poly(limonene), which isn’t volatile or particularly unstable,” Vieira said.

The researchers chose chitosan for the film matrix because it is a polymer of natural origin and has well-known antioxidant and anti-microbial properties. Their hypothesis was that combining the two materials would produce a film with enhanced bioactive properties.

In the laboratory, the scientists compared films with limonene and poly(limonene) in varying proportions to address the challenge of finding a way to combine them with chitosan, since theoretically, they do not mix. The researchers opted for polymerization, a process in which polymers are made from smaller organic molecules. In this case, they used a compound with polar chemical functions to start the reaction and to increase the interaction between the additive and the polymer matrix.

Then, the team analyzed the resulting film to evaluate properties such as antioxidant capacity, light and water vapor protection, and resistance to high temperatures. The results were “highly satisfactory.”

“The films with the poly(limonene) additive outperformed those with limonene, especially in terms of antioxidant activity, which was about twice as potent,” Vieira said.

The substance also performed satisfactorily as an ultraviolet radiation blocker and was found to be non-volatile, making it suitable for large-scale packaging production, where processing conditions are more severe.

The films are not yet available for use by manufacturers, mainly because chitosan-based plastic is not yet produced on a sufficiently large scale to be competitive, but also because the poly(limonene) production process needs to be optimized to improve yield and to be tested during the manufacturing of commercial packaging.

“Our group is working on this,” said Vieria. “We’ve investigated other applications of poly(limonene) in the biomedical field, for example. We’re trying to demonstrate the multifunctionality of this additive, whose origins are renewable.”

Follow the Advocate on Twitter @GSA_Advocate

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

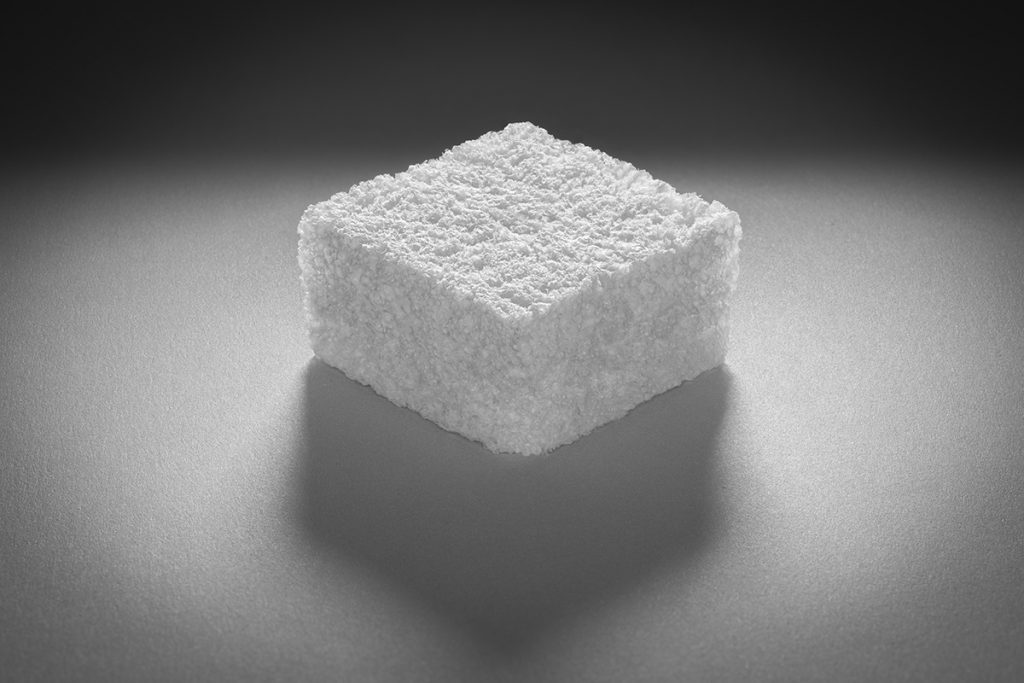

Expanded polystyrene is a ‘waste nightmare’ but could non-EPS seafood packaging reduce ocean pollution?

Expanded polystyrene is common in seafood packaging, but threatens marine life and human health as ocean pollution. A growing number of alternatives are emerging.

Innovation & Investment

Plastic 2.Ocean: Seafood packaging, made from shellfish

A new type of chitosan-based bioplastic, made from shellfish shells, emerges as a potential solution for global food waste and marine plastic pollution.

Responsibility

Slow fish: Preventing waste via packaging

BluWrap shipping technology can cut the seafood industry's abysmal food-waste statistics by dramatically extending the shelf life of fresh product. Company CEO Mark Barnekow's mission is to get fresh fish off airplanes and onto ocean-bound cargo ships.

Innovation & Investment

GFIA winner Cruz Foam secures $18 million in Series A funding

Circular materials company Cruz Foam, which makes alternatives to single-use plastics, secured $18 million in Series A funding, led by Helena.