Queensland aquaculture risks major losses without urgent climate action: Griffith University

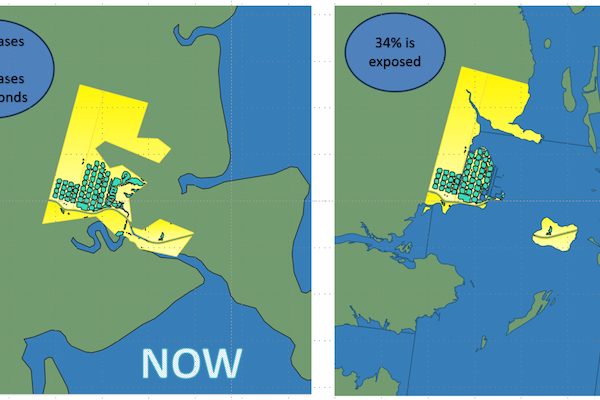

More than 43 percent of Queensland’s productive aquaculture sites could be underwater by 2100, according to new research led by Griffith University – a sobering forecast for Australia’s largest land-based aquaculture state.

“Aquaculture is central to livelihoods and food security, providing security to meet growing human seafood and protein demand without surpassing environmental limits,” said Marina Christofidis, a Ph.D. candidate from Griffith’s Australian Rivers Institute. “But the aquaculture industry is vulnerable to climate change impacts, including sea level rise and so this needed to be assessed.”

The study warns that sea level rise poses a particularly steep threat to shrimp farming, with an estimated 98 percent of sites and half of total production expected to be impacted. The projected annual economic hit? Between (AUS) $36.9 million (U.S. $22 million) and $127.6 million (U.S. $76 million) for shrimp alone, and another AUD$12.6 million (U.S. $7.5 million) to $22.6 million (U.S. $13.5 million) for barramundi.

Queensland’s aquaculture industry is largely concentrated along the coast in pond-based systems, making it especially vulnerable to rising seas.

“Under high-emission scenarios, Queensland is also projected to experience a 0.8 [meter] sea level rise by 2100,” said Christofidis.

To assess the scale of the threat, Christofidis and her team drew on existing datasets from the Queensland government related to coastal inundation and erosion caused by sea level rise. They combined this information with newly developed, satellite-derived data pinpointing the locations of current aquaculture operations and designated aquaculture development areas.

The result was a comprehensive spatial dataset covering 647.14 square kilometers ((approximately 250 square miles), encompassing 341 individual land parcels and 275 active farms – a clear snapshot of the industry’s footprint and its exposure to future sea level rise.

The analysis identified several Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Queensland that are particularly vulnerable to sea level rise. When considering all aquaculture lots, the most affected regions by projected inundation include:

- Cassowary Coast Regional – 3.89 km² (1.50 mi²), or 71 percent of lots

- Whitsunday Regional – 3.63 km² (1.40 mi²), or 39 percent

- Gold Coast Regional – 3.04 km² (1.17 mi²), or 57 percent

- Mackay Regional – 2.42 km² (0.93 mi²), or 100 percent

For productive prawn ponds specifically, the highest vulnerability was concentrated in:

- Gold Coast City – 1.12 km² (0.43 mi²), or 92 percent impacted

- Burdekin Shire – 0.59 km² (0.23 mi²), or 49 percent

- Isaac Regional – 0.36 km² (0.14 mi²), or 42 percent

- Cassowary Coast – 0.30 km² (0.12 mi²), or 20 percent

- Whitsunday Regional – 0.26 km² (0.10 mi²), or 5 percent

- Mackay Regional – 0.073 km² (0.028 mi²), or 100 percent

Barramundi pond sites were also found to be at risk, with the highest projected exposure in:

- Whitsunday Regional – 0.43 km² (0.17 mi²), or 73 percent

- Douglas Shire – 0.23 km² (0.09 mi²), or 44 percent

- Cassowary Coast Regional – 0.085 km² (0.033 mi²), or 97 percent

These figures highlight a pressing geographic disparity in vulnerability – with some regions facing near-total exposure and others seeing more moderate but still significant threats. Christofidis said the results are an “early warning sign” for Queensland’s aquaculture industry.

“We need to integrate climate risks into planning and mitigation strategies in coastal industries like aquaculture both in Australia and globally,” Christofidis said. “For the future of aquaculture in the region, careful considerations should be taken for high-risk aquaculture developments areas located in low elevation coastal zones; developing these areas needs to be adaptable to potential sea level rise in the future to avoid mis-investment.”

Christofidis noted that shifting from traditional aquaculture to more climate-resilient systems — including nature-based solutions like mangroves, green seawalls, artificial reefs, fencing, and netting — could play a critical role in protecting both coastal farms and infrastructure from rising seas.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

How will climate change impact seafood production?

Much work is needed to properly address and prepare for the potential impacts of climate change, and to continue increasing the contribution of seafood production to feed a growing human population.

Responsibility

Give and take: Aquaculture in a future of rising sea levels

With rising sea levels inevitable, aquaculture faces existential uncertainties and confronts its own contributions to the problem.

Responsibility

Ocean temperatures hit record highs in 2024

Ocean temperatures reached record highs in 2024, with deep ocean warming underscoring the urgent need for climate action.

Fisheries

Amid warnings, some marine species exhibit climate resilience as oceans warm

Warming oceans are causing major changes, yet some fish species, where the waters are most in flux, are showing climate resilience.