The minimum size limit of 254 mm total length in Florida state waters appears to be too low to protect maturing females in particular

The grey snapper (Lutjanus griseus) is an important fish species for recreational and commercial fisheries in the United States, most notably in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM). The GOM stock is currently not over-exploited; however, the spawning stock biomass overall has been decreasing since the mid-1970s. As fishing regulations become more restrictive on other higher-profile reef fish species, such as gag grouper and red snapper, fishing pressure would be expected to increase on grey snapper in the near future. In fact, in 2024, the GOM grey snapper quota (annual catch limit) increased from 2.23 to 5.73 million pounds.

To effectively manage a reef fish species, such as the grey snapper, it is critical to incorporate their reproductive biology – including fecundity, sexual maturity and spatiotemporal dynamics of spawning – into their stock assessments to be able to estimate recruitment and avoid overexploitation of the stock. However, there is a general lack of detailed information on the reproductive biology of grey snapper from the west coast of Florida in the eastern GOM.

When these reproductive parameters are unknown or limited, such as with GOM grey snapper, the female spawning stock biomass (SSB) is used as a proxy for fecundity in the stock assessments. This method assumes an isometric (equality of measured) relationship between body weight and fecundity. However, across many fish species, there is a disproportionate increase in fecundity per unit body mass with female size and age. These fish are commonly referred to as Big Old Fat Fecund Females (BOFFFs) and they often spawn for a longer duration and release batches of eggs more frequently than younger, smaller females, thus directly impacting estimates of total annual fecundity. BOFFFs, in addition to greater reproductive output, typically have larger and higher quality eggs that can lead to increased survival of their larvae.

This article – summarized from the original publication [Wechsler, A. et al. 2024. Age- and Size- Based Reproductive Potential of Gray Snapper (Lutjanus griseus) in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico. Fishes 2024, 9(12), 513] – reports on a study to determine the spawning parameters of gray snapper and to quantify female reproductive potential on an age- and size-basis for fishes collected off the west coast of Florida, USA.

The study was conducted by the University of Florida (Gainesville, Florida, USA) with gray snappers sampled (total 4,653 fish) from the west coast of Florida for two consecutive years from March 2022 to December 2023. Sampling was focused over the summer months during the presumed spawning season as well as over the moon phases to address lunar periodicity in spawning. Fish morphometric data was collected, and otoliths (biomineralized ear stones that contribute to hearing in fish) and gonads were removed for processing and analyses.

For detailed information on the experimental design, fish collection, otolith and histology (study of the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues) preparations, and sample analysis and determination of various reproductive characteristics of the sampled fish, refer to the original publication.

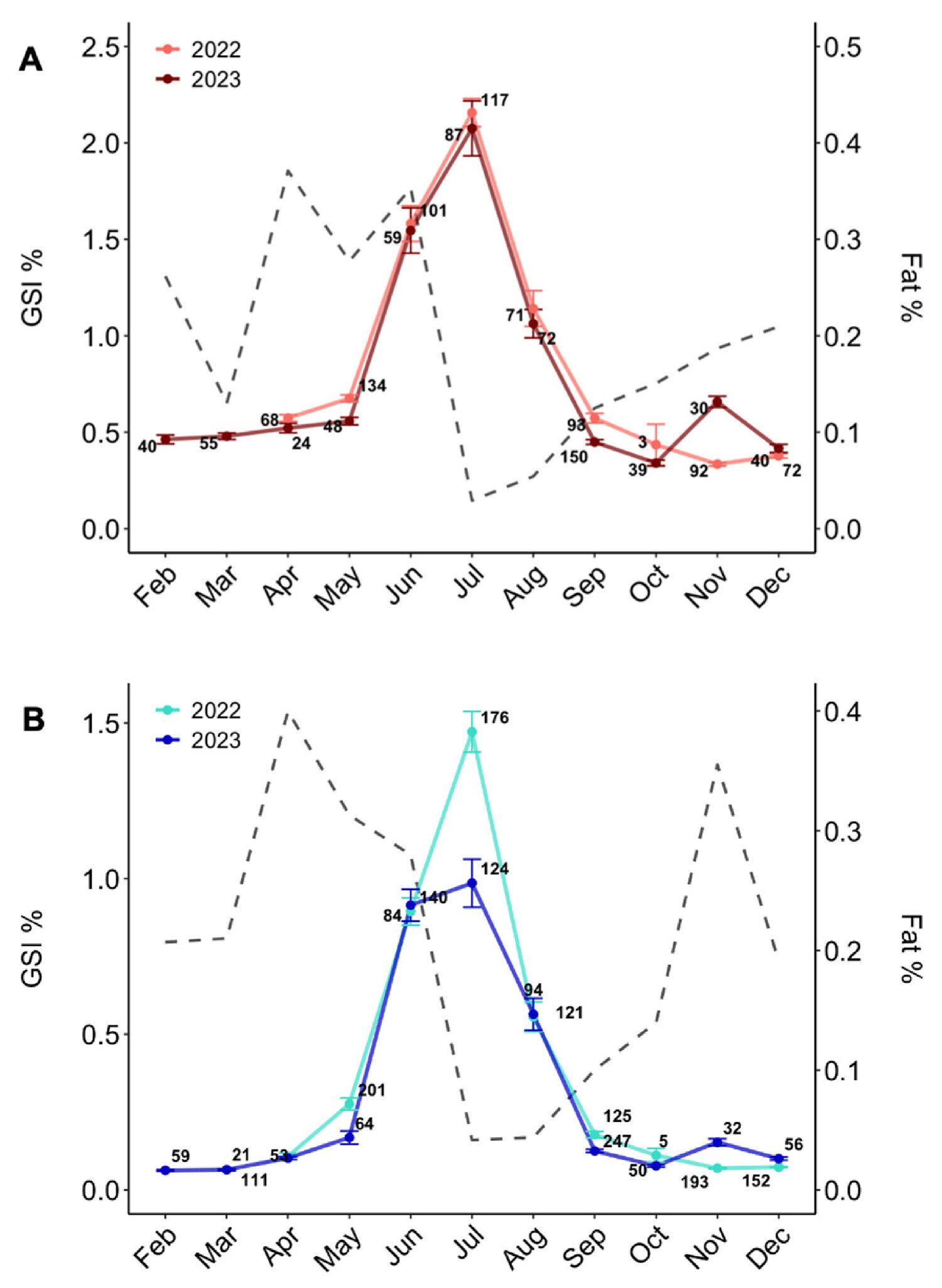

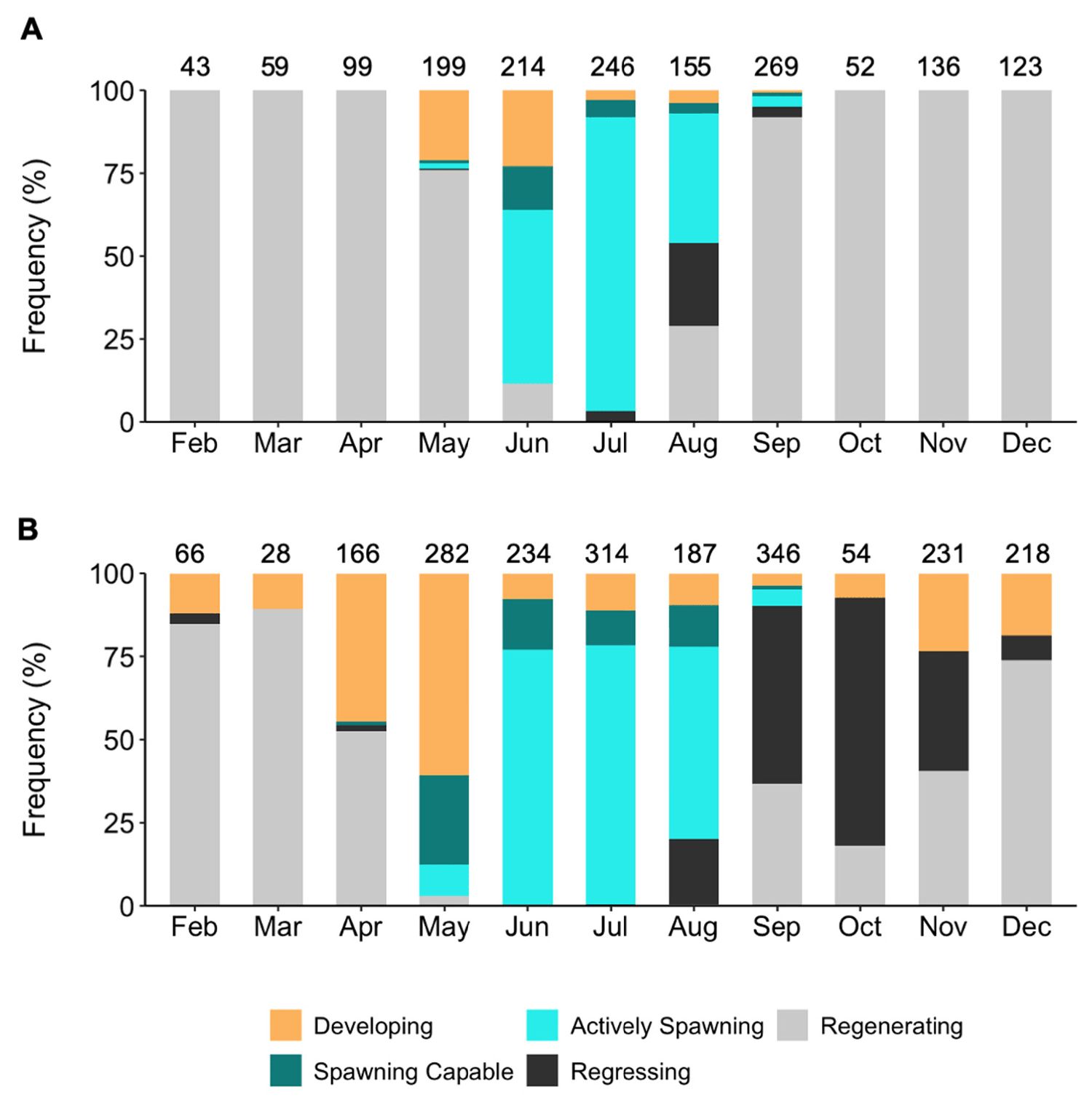

Spawning seasonality

Overall, the summer spawning season for grey snapper off the west coast of Florida appeared to have a shorter duration than those previously reported. The majority of grey snapper spawning was observed from June to August, with peak spawning in July, which was evident by the increase in gonadosomatic indices (GSI, the calculation of the gonad mass as a proportion of the total body mass) and the highest spawning fractions. Prior studies have quantified spawning from May to September; however, fewer than 3 percent of females and 10 percent of males were spawning in the months of May and September in the present study. Males become spawning-capable earlier than females, which may contribute to the reports of a more extended spawning season.

For example, Domeier et al. observed males to be ready for spawning as early as March off Key West (Florida), although they did not observe females ready to spawn until mid-June. grey snapper spawning duration may also be related to warmer water temperatures, with spawning more drawn out in shallower or warm temperate/subtropical areas of South Florida compared to the offshore waters of the Florida Middle Grounds.

Kim noted a similar trend for grey snapper sampled in the northern GOM off Alabama and Mississippi where the spawning fraction increased from 14 percent (300–399 mm TL) to 30 percent (600–699 mm TL) and from 17 percent (age 3–5) to 31 percent (age 16–25). Fitzhugh et al. estimated the spawning fraction at 37 percent for females with around 330–370 mm TL and ~60 percent for fish with ≥500 mm TL, which was more than double the estimates provided in our study and by Kim.

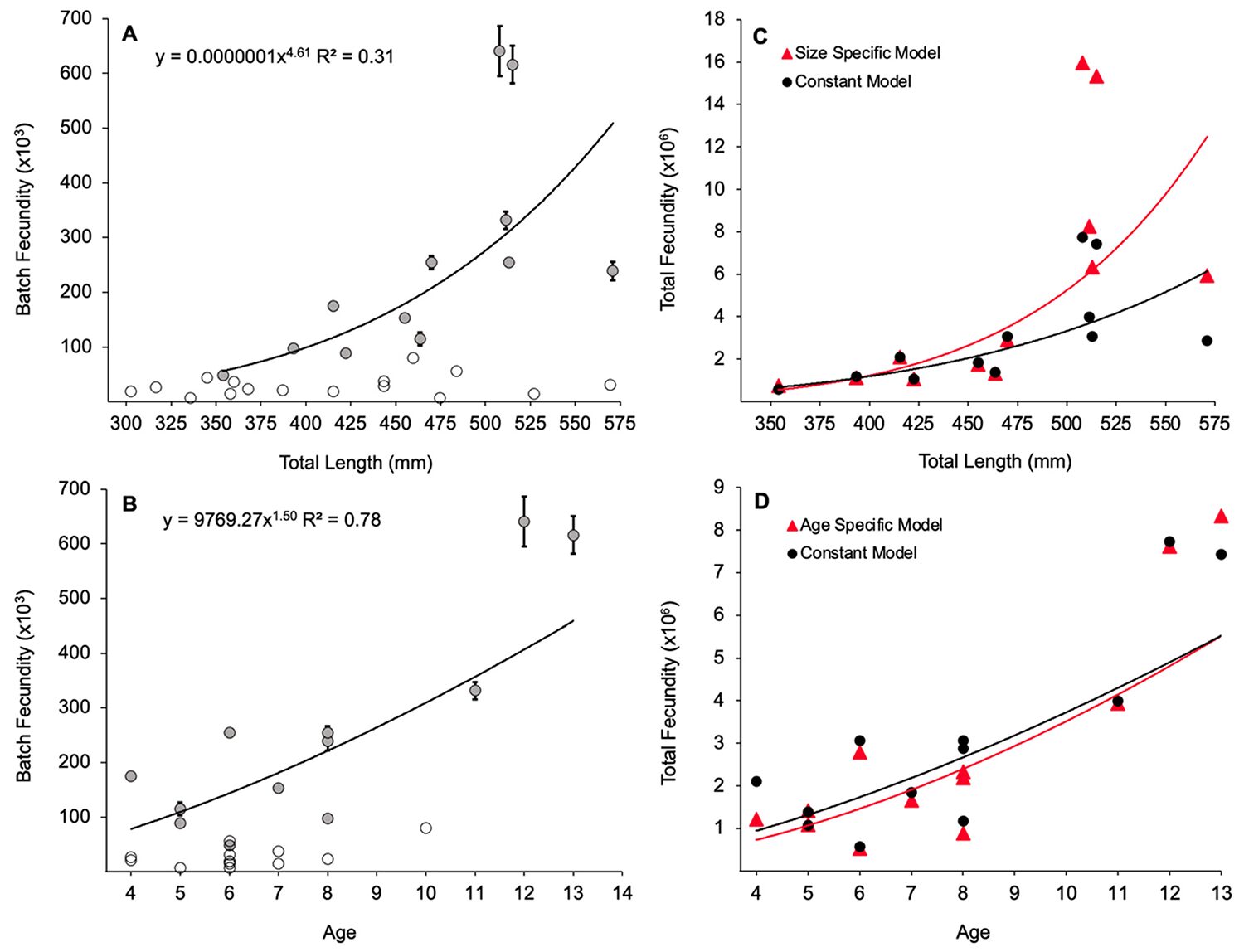

Batch fecundity

Batch fecundity estimates as a function of fish length supported that larger females release disproportionately more eggs than smaller females, as evidenced by the increased hyperallometric scaling (scaling relationship between the size of a body part and the size of the body as a whole) in relation to body weight. Batch fecundity as a function of age also suggested such a relationship. These relationships could be potentially improved with further sampling of females that were in hydration, which were limited in this study as well as in studies by other researchers. The difficulty, in part, of obtaining females in hydration may be explained by the rapid maturation process of oocytes (immature egg) before ovulation in warm water, indeterminate (oocytes are continuously recruited and spawned in multiple batches over the spawning season) species.

In red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), Jackson et al. found that it took five hours for oocytes to progress from early hydration to being fully hydrated and ovulation occurred within five hours after attaining hydration, thus leading to a 10-hour timeframe during which hydrated oocytes would be visible in the ovaries. It is therefore possible that females in hydration are temporally limited or that the hydration process may be quicker for grey snapper; however, the timing of this process is currently unknown for grey snappers.

Lunar periodicity

Many fishes spawn in accordance with lunar cycles for a variety of reasons. Lunar phases may act as an initiation for large spawning aggregations to form. But information on the timing and movement of grey snappers into spawning aggregations is unknown, and more research is needed to determine their fine-scale movements during the spawning season and whether aggregation abundance increases with any particular lunar period. Fish have also been hypothesized to spawn during the darkness of the new moon to reduce predation on eggs and larvae, or on the brightness of the full moon to reduce predation on the spawning adults by large, crepuscular/night-time predators.

Female grey snappers in this study showed increases in oocyte maturation (OM) and post-ovulatory follicles (POFs; cells remaining within the ovary after the ovulation of the previously enclosed oocyte). POFs around the new and first-quarter moons. Denit and Sponaugle also estimated that spawning on the southeastern coast of Florida occurred during the new and first-quarter moons based on back-calculated spawning dates from young-of-the-year grey snapper. Other researchers have suggested that grey snapper in the Florida Keys spawn on the full moon, based on their observation of spent females shortly after the full moon in September.

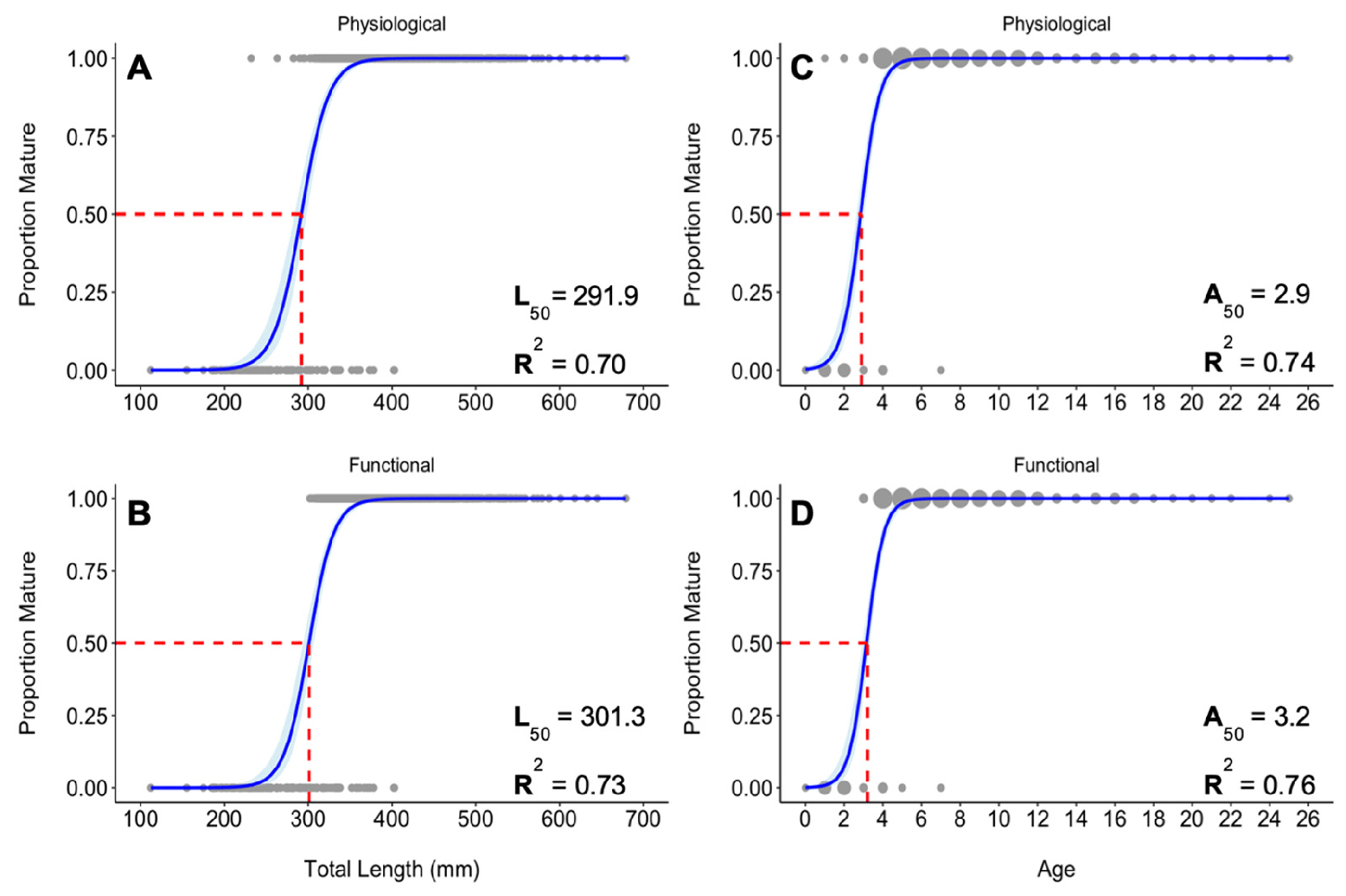

Sexual maturity

For grey snappers, the size at 50 percent sexual maturity for females was estimated to be slightly greater for functional maturity (301 mm TL) compared to for physiological maturity (292 mm TL). Additionally, both physiological and functional maturity estimates were greater in this study compared to those in prior studies in the U.S. GOM. Other researchers have estimated physiological maturity for the species at 272 mm TL and 273 mm TL and functional maturity at 290 mm TL.

The current minimum length limit for grey snappers in Florida state waters (<9 nautical miles, nm, from the coast in the Gulf of Mexico) is 254 mm TL and in federal waters (>9 nm offshore) is 305 mm TL. Although our sampling primarily focused on mature female grey snappers in spawning aggregations offshore, there was no indication from our inshore sampling that females collected in state waters were sexually mature when <300 mm in TL (functional maturity). Given that 50 percent of the population of female grey snapper are not sexually mature until they reach a 301 mm TL, it may be necessary to adjust the minimum length limit in Florida state waters to ensure that an appropriate proportion of females inshore have the chance to mature and make the ontogenetic movement offshore for reproduction prior to potential harvest.

More information regarding the spatial distribution of grey snapper is needed to determine the age and timing of migration offshore and if it coincides with sexual maturity. For both the inshore and offshore collections, the sex ratio found in this study was not 1:1 and there was a greater proportion of males to females. The sex ratio of a stock is an important metric for calculating the size of the stock and hence the reproductive contribution of females. Other researchers have previously reported a nearly 1:1 ratio and this warrants further investigation to determine if spatially distinct areas of the population are sex-skewed.

Perspectives

This study developed the first estimates of the age- and size-specific reproductive parameters that affect total fecundity for grey snapper in the eastern GOM. It also provided evidence that Big Old Fat Fecund Females (BOFFFs) had a disproportionately higher total annual fecundity by spawning in higher proportions during the spawning season and by spawning more often than smaller, younger females. It would be critical to understand whether BOFFFs contribute more to the absolute total egg production since these females may make up a relatively low proportion of the stock.

If future stock assessments continue to use female spawning stock biomass, which assumes constant age- and size-reproductive parameters and therefore an isometric (equality of measure) rather than hyperallometric relationship to fecundity, the reproductive potential and thus stock status of grey snappers may be inaccurate. It is thus important that future stock assessments consider the various size- and age-based parameters for grey snappers, along with the new estimates of spawning duration and sexual maturity that may represent their reproductive potential more accurately.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Debra J. Murie, Ph.D.

Corresponding author

School of Forest, Fisheries and Geomatics Sciences, University of Florida, 7922 Northwest 71st Street, Gainesville, FL 32653, USA

Tagged With

Related Posts

Intelligence

Assessing the genetic potential to improve omega-3 content in farmed Malabar red snapper

Identifying and selecting fish with favorable genetic profiles means that future generations of Malabar red snapper could contain more omega-3s.

Fisheries

Comparing DNA extraction protocols from biological tissues of Caribbean red snapper

Three commercial kit protocols produced similar results for extracted DNA amount and quality so choice depends on financial resources and time.

Intelligence

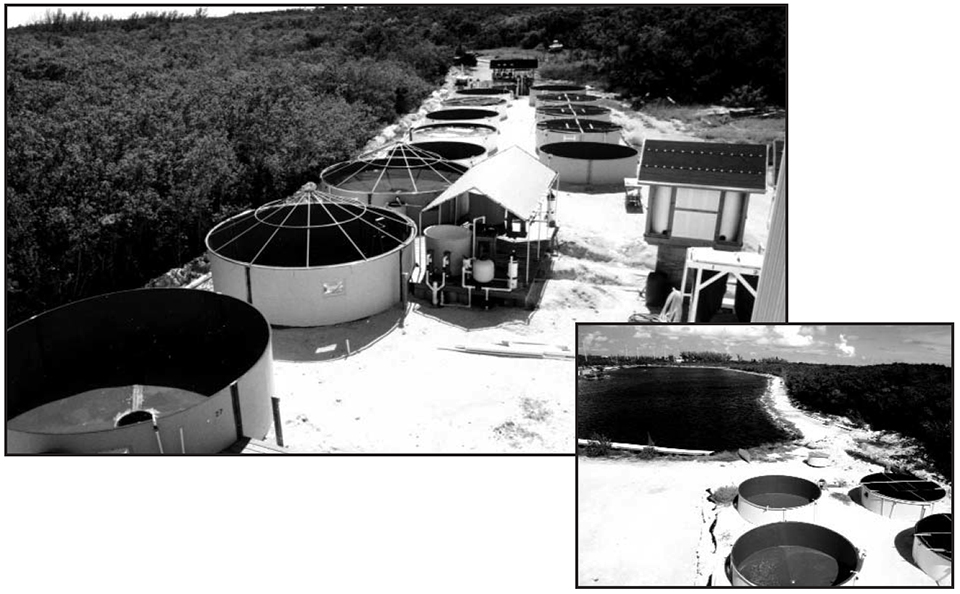

Commercial marine finfish hatchery in the Florida Keys reports on first production trials of mutton snapper

Grassy Key Aquatic Center and the University of Miami combined to refine aquaculture technology of mutton snapper other marine fish species.

Fisheries

The hidden benefits and risks of partial protection for coral reef fisheries

Partial protection of coral reef fisheries can boost production, ease fishers’ efforts and ultimately alter the composition of their yields.