Ocean resources like seaweed, old fishing nets and invasive species are replacing the yarns, leathers and plastics used in the fashion industry’s apparel and packaging

The fashion industry is not known for being on the cutting edge of environmental change. Several growing businesses are trying to change that by creating products useful to the industry that are made from plants or species that originate in ocean or fresh-water environments. In some cases, they’re eliminating potential pollutants and giving them a new, pragmatic future.

Back in 2013, David Stover noted an abundant source of waste in fishing nets that were not being recycled. He proposed to the Chilean government that his company, Bureo, would purchase those nets, which are made from a durable, engineered plastic, and convert them into yarn for the fashion industry. “We took this untapped resource, which we wanted to keep out of the ocean, and matched waste with design and the need for quality materials,” Stover told the Advocate.

Bureo now buys end-of-life fishing nets from small-scale fisheries in Chile, Peru, Argentina, Ecuador, Mexico and in the United States. The nets are sorted, washed, pulverized and melted in processing facilities in Ecuador and Peru. The material then undergoes de-polymerization, a process in which the plastic is broken down, filtered and converted into Net Plus, a yarn that can be used to make clothing, surfboards or sunglasses.

Some 20 companies have come on board to purchase and use Net Plus, among them Finnesterre, Outer Known, Patagonia, Future Spins and Coast Sunglasses. With such strong interest from the fashion industry, Bureo has scaled up its net-collection activities considerably, from 100,000 pounds a decade ago to 33 million pounds in 2023.

Stover said Patagonia was an early adopter of Net Plus, starting with 50,000 metric tons (MT, tonnes) of Net Plus product in 2014. “Today they’re using 1,000 tons per year of recycled nets, and we have dozens of companies actively looking at replacing their virgin plastic with fishing nets,” he said.

“The apparel industry has changed a lot in the past decade,” he added. “There’s a lot of focus on removing all virgin plastics from their design chains, and using recycled products rather than producing more and more new plastic.”

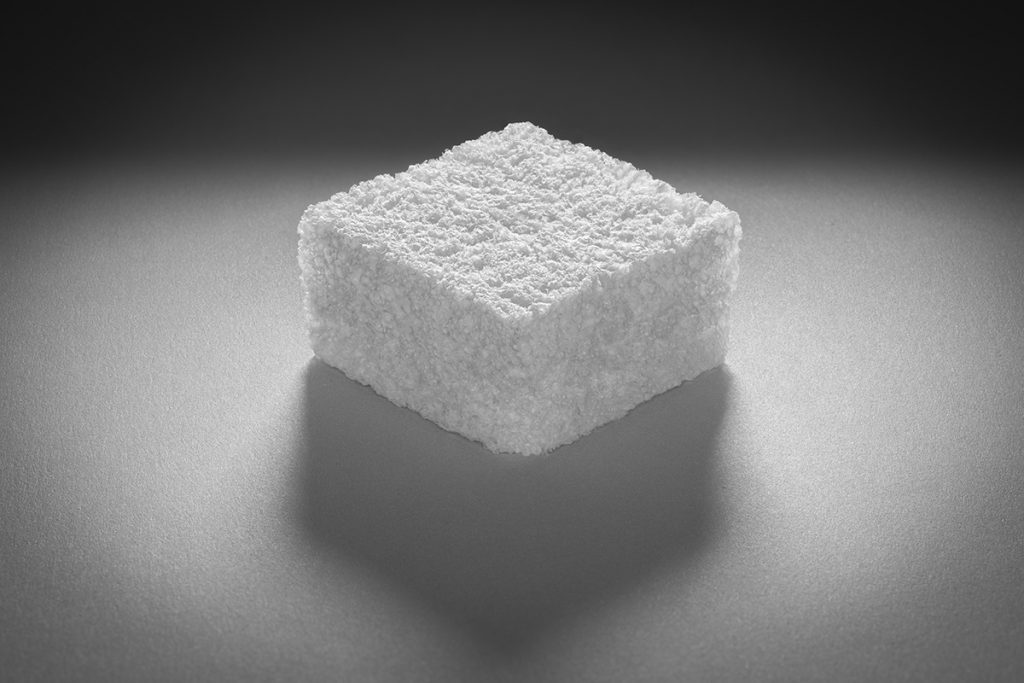

The removal of plastic from the supply chain is the premise for Sway, a San Francisco Bay Area company that transforms farmed seaweed and plants into a resin that mimics the look and feel of plastic. The resin is designed to fit the same machinery that creates traditional plastics, but unlike traditional plastics, Sway’s TPSea™ (Thermoplastic Seaweed) decomposes within 90 days in industrial facilities and within 180 days in home composting facilities, TUV Austria standards.

The seed-stage startup plans to reach commercial volumes of seaweed-based flexible packaging film production in 2025. Fashion brands prAna, Florence, Faherty and Alex Crane have come on board to test Sway Polybags for e-commerce packaging.

There’s a lot of focus on removing all virgin plastics from their design chains, and using recycled products rather than producing more and more new plastic.

“In four years, we’ve taken our product from prototype to market-ready production,” said Alyssa Pace, communications lead at Sway. “We are sourcing seaweed from all over the globe and we have no doubt that there’s enough responsibly farmed seaweed in the world to fill our product needs.”

Sway’s packaging costs more than traditional plastic packaging and is also more expensive than renewable packaging derived from other agricultural products like corn, potato or sugar cane. “In time, as the seaweed industry grows, we’ll be able to drive costs down and eventually compete with plastics,” she said.

The response from the fashion industry has been overwhelmingly supportive, she added: “We’ve seen interest from brands, individuals and design firms, and we have over 1,000 inquiries in our pipeline from companies that want to explore circularity, regeneration and feedstocks that are really better for the planet.”

Inversa Leathers is also committed to bettering the planet through apparel. The Tampa, Fla.-based company is focused on two invasive fish species that are wreaking havoc on the ecosystems they are now regrettably in. Inversa does its party by turning their skin into leather that they sell to brands that manufacture jewelry, purses, wallets, belts and shoes.

Founder Aarav Chavda, a recreational scuba diver who loved diving the coral reefs in the Caribbean, was distressed by the destruction wrought by lionfish, an Indian Ocean and South Pacific fish with no natural predators that was released off the coast of Florida in the 1980s.

“A lionfish will consume 70,000 native fish over its lifetime, so they literally eat their way through a coral reef,” he said. “Within five weeks of lionfish showing up, there’s a 79 percent decline in juvenile fish biodiversity. And each lionfish can lay 2 to 6 million eggs per year. With this kind of reproduction rate, lionfish are the poster child for invasive species.”

A material scientist by training, Chavda realized that with its parallel-running fibers, lionfish skin could be transformed into an extremely durable leather useful for making clothing accents and jewelry. Inversa Leathers partners with Caribbean fishing cooperatives, incentivizing divers to spear-hunt lionfish in the most environmentally sensitive areas. Inversa uses the skin for leather while the filets are used for human and pet food.

“The commercial incentives of scale are perfectly aligned with the environmental and sustainable incentives of scale,” he said. “While eradication of lionfish is impossible, the take rate allows a concentrated pattern of lionfish removals on high priority biodiversity-sensitive areas. But because lionfish have a refresh rate of 2 to 6 months, you have to keep coming back to give the reefs time to recover.”

Silverfin carp is the other invasive species whose skins Inversa Leathers is selling to brands needing leather for handbags, purses and footwear. The take rate for these fish is higher because they are netted rather than spearfished but the damage they are causing is just as severe.

“Silverfin carp has displaced 90 percent of the native biomass of the Mississippi River basin,” Chavda said. “They’ve outcompeted and starved out all the other fish. It’s a depressing story, but if you put pressure on the population, you can have great recoveries.”

Inversa works on consistent removal of silverfin carp with multiple communities across the Mississippi Delta. Brands using carp skin include W. Kleinberg, which makes belts, wallets and other leather goods accessories, and designer Chris Ploof, who is using lionfish and silverfin in jewelry. Brackish is another brand using lionfish in its jewelry.

He doesn’t have time to scuba dive any more, but Chavda is feeling optimistic about the future. “My dream is to build a network of brands looking for our leathers at various price points,” he said. “As we put more pressure on these populations of invasive species, we’ll have the partners to help us take the density curve down. This is an exciting space to be operating in and we’re seeing a lot of commercial interest in our products. This is a great solution to bring invasive species under control while also providing a unique way for fashion consumers to participate in an exciting story of regeneration.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Lauren Kramer

Vancouver-based correspondent Lauren Kramer has written about the seafood industry for the past 15 years.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Plastic 2.Ocean: Seafood packaging, made from shellfish

A new type of chitosan-based bioplastic, made from shellfish shells, emerges as a potential solution for global food waste and marine plastic pollution.

Fisheries

‘Regulation is pushing toward greenifying materials’: How one innovator is upcycling seafood waste into biodegradable packaging foam

GOAL 22: Cruz Foam’s biodegradable packaging foam made with shrimp shells is a finalist for GSA’s inaugural Global Fisheries Innovation Award.

Intelligence

An examination of seafood packaging

Some substances can migrate from plastics and other seafood packaging materials into the product. Even if the substances are not harmful, they can affect the flavor and acceptability of the food.

Innovation & Investment

‘Everyone is going to need a lot of seaweed’: Maine-based seaweed polymer innovator wants fisheries and aquaculture to quit plastics

Viable Gear Founder Katie Weiler joined the Advocate and Aquademia to discuss making lobster bait bags and other products with a seaweed polymer.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)