Study refutes published comments that ornate spiny lobsters are globally endangered based on its conservation listing in China

Fisheries genomics is a swiftly growing field with significant potential to support fishery management, conservation and stock identification. This is important because fisheries are a vital component of the world food system, but there are large disparities between the regional status of stocks, largely attributed to intensity of fisheries management. Reliable and objective science is essential to inform conservation and fisheries policies that can be controversial but have major implications for biodiversity conservation, fisheries management, livelihoods and trade.

Genetics approaches and particularly close-kin mark-recapture, CKMR (alternative method for estimating abundance and other demographic parameters using kinship relationships from genetic samples) are transforming the ability to assess the status of conservation and fishery species. The CKMR approach is increasingly being applied to both fished and endangered marine species. Together with approaches such as genome sequencing techniques, this improves understanding of the population structure of species like several critically endangered ones.

Less attention has focused on the use of genetics approaches to support management and conservation of crustaceans such as spiny lobsters (which includes the genus Panulirus), which support coastal fisheries and are highly prized on international seafood markets and hence economically valuable but subject to overfishing. However, various authors have reported

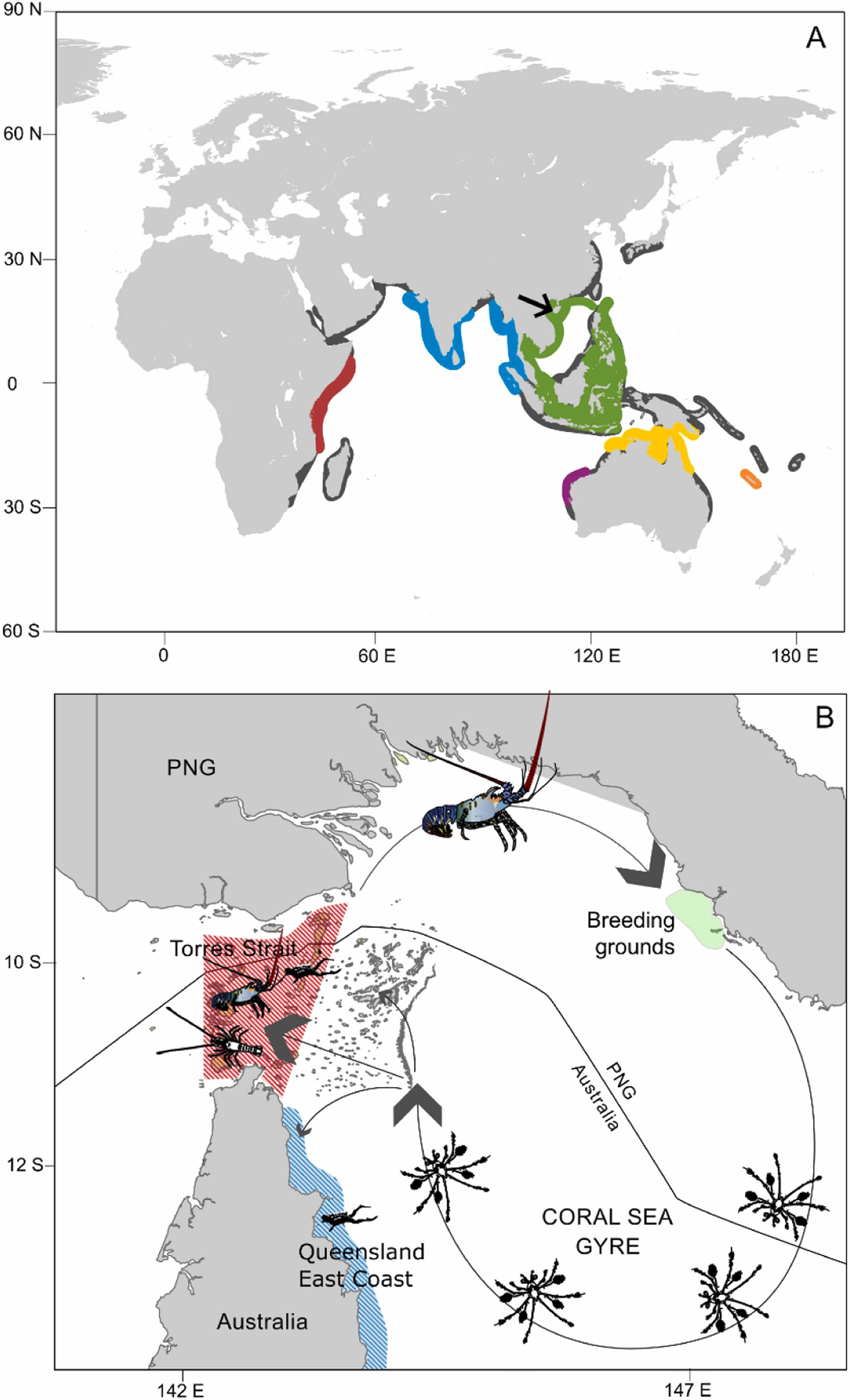

unique genetics of lobster species supporting the need for separate management of the different lineages. For example, Farhadi et al. proposed five management units across the range of the ornate spiny lobster (Panulirus ornatus) – a widely distributed crustacean species that is socioeconomically important to indigenous and local communities – and identified significant genetic differences between northern Australian and Southeast Asian lobsters (Fig. 1A).

Although previous studies sampled widely across the Indo-West Pacific Ocean, they did not include China, but this gap has recently been filled by Ren et al., who mapped the chromosome-level genome of male adult P. ornatus obtained from Hainan in southern China. We note that this was not a population level study and thus cannot inform on population status, but it does contribute to mapping lobster genetic diversity.

In this article – summarized from the original publication – we draw on evidence from regionally abundant populations to refute published comments that P. ornatus is globally endangered based on its conservation listing in China.

Ornate spiny lobsters are not globally endangered P. ornatus is widely distributed across both the Indian Ocean and western Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1A), including northeastern Australia, southern China and southern Japan. Authors have reported that this prized fishery species is classified as a Class II species on China’s National Key Protected Wild Animals List, which characterizes them as a species of conservation concern. Per Ren et al., this conservation status is presumably based on an assessment of populations within Chinese waters.

We agree with Ren and co-authors that, as with many targeted marine resources, there are a number of challenges facing P. ornatus stocks, including climate change and habitat degradation. Hence, ongoing conservation and sustainable management are significantly important. However, the statement by these authors that “P. ornatus is in decline” or “is an endangered species” needs to be better qualified as it certainly does not apply globally. China’s Class II ranking identifies the species as potential key protected wild animals.

This listing status is similar to CITES Appendix II, which includes species not necessarily threatened with extinction but for which trade-controls are recommended to support conservation measures. However, P. ornatus is not listed on CITES Appendices I, II or III. The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN) classifies P. ornatus as stable and of Least Concern when considering its global distribution, albeit recognizing the assessment dates to 2009.

Monitoring and sustainable management of lobster stocks

In the Indian Ocean, P. ornatus, along with other spiny lobsters (Panulirus spp.) typically do not support large commercial fisheries but contribute to artisanal fisheries and are socioeconomically important to local communities. Given their high value they are susceptible to heavy fishing pressure, but there is no evidence to our knowledge that would suggest this species is endangered in this region.

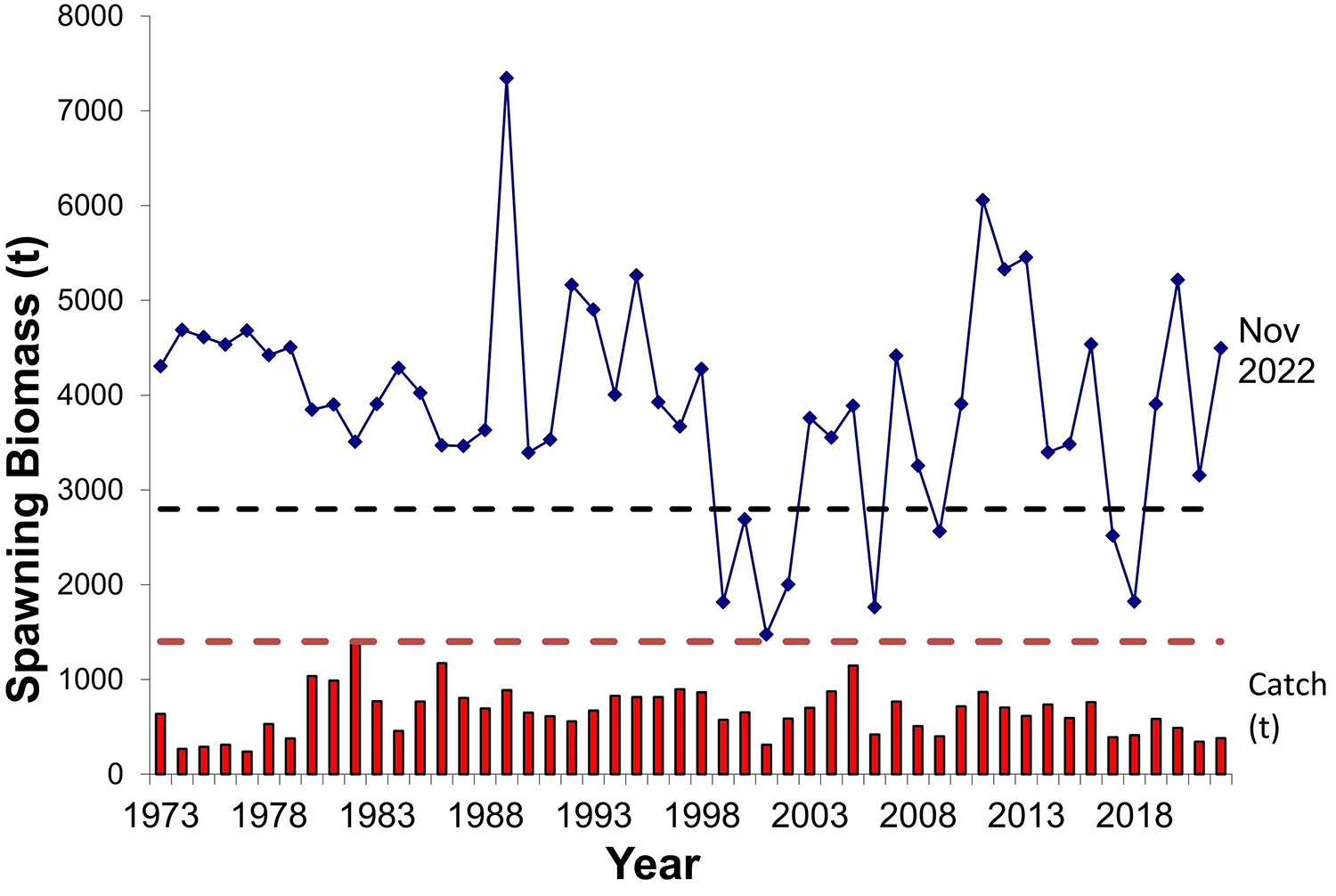

In northeastern Australia, Torres Strait (Fig. 1B) provides an example where P. ornatus stock abundance is high or even close to pristine levels (Fig. 2). For example, annual monitoring of P. ornatus stocks in Torres Strait reveals dense and stable, albeit naturally highly variable, population abundance. This is in part due to implementation of precautionary management based on a culture of strong stewardship by the indigenous Torres Strait fishers who rely on a P. ornatus fishery, locally termed “kaiar.”

The northeastern Australian P. ornatus stock is shared with Papua New Guinea. This same northeastern Australian population is fished along the country’s east coast (Fig. 1B), where large spatial closures comprising the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park provide additional protection for this species and contributes to Australian stocks not being threatened or endangered.

The northeastern Australian population is largely self-seeded, with mature lobsters typically migrating out of Torres Strait across the Gulf of Papua to breeding grounds along the coast of Papua New Guinea. Here, eggs are released, and larvae enter the Coral Sea gyre that transports them back to northeastern Australia, where they settle six months later (Fig. 1B). There is some mixing between Torres Strait and the Queensland East Coast stock jurisdiction (Fig. 1B), and the same Torres Strait stock is fished by both Australia and Papua New Guinea.

Strong retention in the Coral Sea gyre is, in part, a reason for the distinct genetic break between northeastern Australian and south-east Asian populations (Farhadi et al., 2022) and the creation of a P. ornatus ‘hotspot’ in Australia. Over thousands of years, this complex but efficient lifecycle of P. ornatus in northeastern Australia has allowed ‘kaiar’ to weave its way into the cultural, social and economic fabric of the Indigenous peoples of the Torres Strait. Good custodianship and precautionary management approaches have allowed the dependence of Indigenous peoples on this high-value species to continue.

The spatial distribution and abundance of P. ornatus is highly variable throughout its range, including in the South China Sea region. The highest abundance historically occurred along the central Vietnamese coastline, with lower abundance in the northern part of the South China Sea including the Hainan region. Ornate lobsters are found as far north as southern Japan, and largely absent from northern (non-tropical) Chinese waters based on distribution maps and connectivity modeling.

Although there is limited understanding of the complex oceanography of the Southeast Asian archipelago, modeling of plausible larval dispersal pathways suggests spawning grounds for lobsters recruiting in southern China and Vietnam are located in the Philippines. Concerns have been expressed in the past that non-sustainable capture of wild lobster seed for aquaculture grow-out in Vietnam could be negatively impacting regional P. ornatus populations.

Can automatic measuring replace humans when evaluating a shrimp fishery?

Perspectives on conservation genomics to support global trade in fisheries

There is no doubt that the success of conservation genetics for wild populations requires good global representation and sharing of big data. The identification of significant genetic differences between northeastern Australian and Southeast Asian lobsters has important consequences for fisheries management and aquaculture development.

These studies and the sharing of data will enable development of genetic approaches to differentiate between northeastern Australian and Southeast Asian lobsters, and indeed other stocks from elsewhere in the Indo-Pacific. This would be a valuable addition to the collection of management information by indicating origin between wild-caught lobster from sustainably managed fisheries (e.g. Torres Strait) versus depleted or recovering stocks, or to pinpoint the origin of aquaculture-grown ornate lobsters, for example in Vietnam.

Australian lobster fisheries such as the Torres Strait fishery have traditionally relied on export of live lobsters to Asian markets. In recent years, this fishery has been specifically impacted heavily, first by supply chain disruptions due to COVID, and then by ongoing trade sanctions imposed by the Chinese government on a variety of Australian commodities including spiny lobsters. Although trade sanctions may be lifted, there remains an issue around conservation concerns for P. ornatus, given its status in China.

Consistent with growing use of new and emerging genetic technologies to improve conservation and fisheries management, we encourage uptake of approaches such as detailed in the road map of Andersson et al. for using genome sequencing to inform genetic markers. Ultimately, we therefore encourage research towards cost-effective point-of-origin testing to promote trade of sustainably managed natural resources.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Éva Plagányi, Ph.D.

Corresponding author

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Environment, Queensland BioSciences Precinct (QBP), St Lucia, Queensland 4072, Australia

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Atlantic cod genomics and broodstock development project

The Atlantic Cod Genomics and Broodstock Development Project has expanded the gene-related resources for the species in Canada.

Health & Welfare

Genomic selection for resistance to White Spot Syndrome Virus in Pacific white shrimp

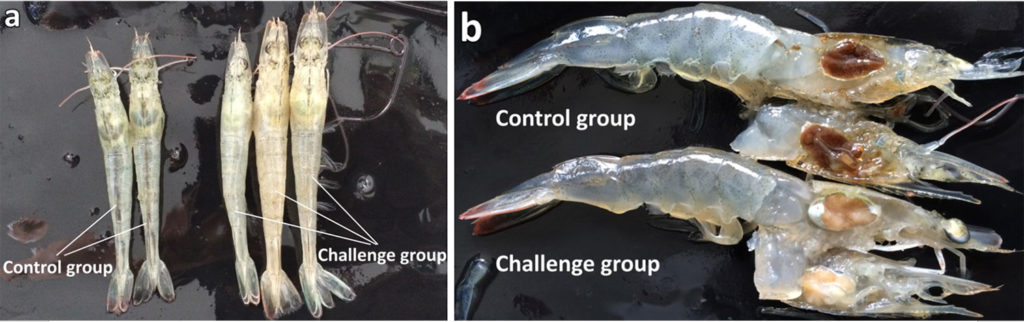

Genomic selection techniques show significant potential for enhancing the species’ resistance to White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) infection.

Health & Welfare

Emerging disease: Shrimp Hemocyte Iridescent Virus (SHIV)

SHIV is a new Pacific white shrimp virus in the Iridoviridae family. Authors also developed an ISH assay and a nested PCR method for its specific detection.

Responsibility

Hatchery production of spiny lobsters

Spiny lobsters are a premium seafood whose culture has depended on wild-caught seedstock. An Australian company is helping shift the farming paradigm to more sustainable hatchery production.