Alternative lipid composition affects tissue fatty acid profile

Several ingredients are used in the aquafeed industry, but proteins and lipids of marine origin (i.e., fish meal and oil) are considered some of the most important raw materials. The aquaculture industry is the largest consumer of these ingredients, currently commanding 68 percent of fishmeal production and 74 percent of fish oil production (or more) on an annual basis. Finite supply from reduction fisheries unlikely to increase their yield and growing demand has led to increases in their prices, and driven the search for and development of alternative protein and lipid sources to sustain the sustainable expansion of the aquaculture industry.

The fatty acid profile and associated nutritional value of fillets are characteristically changed when fish oil is spared or replaced by vegetable or terrestrial animal origin alternatives, reflecting the composition of the alternative lipid used. Dietary fish oil replacement may also negatively affect fish survival, growth and growth efficiency if the diet does not supply adequate levels of essential fatty acids, in particular long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs). The scale of growth suppression and/or tissue modification depends on various factors, including fatty acid composition of the alternative lipid and level of replacement, the target species, feed formulation and others.

Preserving tissue fatty acid profile and retaining (or restoring) desired levels of beneficial n-3 LC-PUFAs is more challenging than maintaining growth. Additionally, the alternative lipid source selected is relevant; and dietary fatty acid composition, mainly the balance of saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), or C18 polyunsaturated fatty acids (C18 PUFAs) may affect the result when trying to spare or replace fish oil.

For many years there has been interest in developing commercial culture of the Florida pompano (Trachinotus carolinus) a good candidate for intensive aquaculture. Its nutritional requirements have been studied for many years, but there are few published studies addressing lipid nutrition of Trachinotus spp. Although without definitive evidence, we assumed that Florida pompano – like other marine, carnivorous fish species – exhibit little to no capacity for LC-PUFA synthesis and must consume these critical nutrients directly. Recent findings suggest that LC-PUFA requirements may be satisfied more efficiently in the context of SFA- or MUFA-rich diets than C18 PUFA-rich diets. Consequently, we carried out a study to evaluate production performance and tissue composition of juvenile Florida pompano fed diets containing fish oil or 25:75 blends of fish oil and various other lipid sources. This article is adapted and summarized from Aquaculture 458(2016): 177–186.

Study setup

We formulated six feeds with a moderate level of menhaden fish meal (267.4 g/kg) to contain approximately 44 percent crude protein, 14 percent crude lipid, and vary only in their supplemental lipid source and fatty acid composition (C18 PUFA, MUFA, and SFA content).

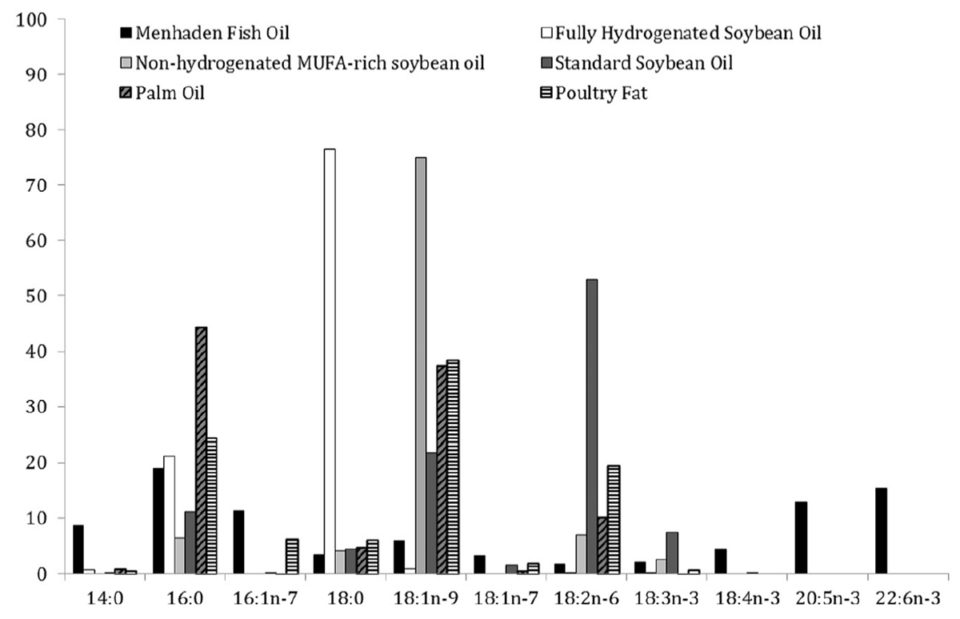

Specifically, diets contained menhaden fish oil (FISH) or 25:75 blends of fish oil and standard, C18 PUFA-rich soybean oil (C18 PUFA SOY), non-hydrogenated MUFA-rich soybean oil (MUFA SOY), fully hydrogenated, SFA-rich soybean oil (SFA SOY), palm oil (PALM) or poultry fat (POULTRY). Fig. 1 summarizes the typical fatty acid composition of the lipid sources used.

The fish oil sparing ratio, 25:75 blends of fish oil and alternative lipid sources were selected to ensure the diets contained enough LC-PUFAs to meet or exceed the presumed essential fatty acid requirements of Florida pompano. The experimental feeds were prepared at the Center for Fisheries, Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences (CFAAS; Carbondale, Ill., USA) according to standard internal practices. Reserved crude lipid samples were analyzed for fatty acid composition according to CFAAS standard procedures.

The feeding trial was conducted at the Virginia Seafood Agricultural Research and Extension Center (VSAREC, Hampton, VA, USA) facility in a recirculating aquaculture system with eighteen, 300-L fiberglass tanks and assorted life-support equipment. Juvenile Florida pompano (43.4 ± 0.2 grams, mean ± SE) were stocked at 10 fish/tank and dietary treatments were randomly assigned in triplicate tanks (N = 3). All fish were fed to apparent satiation, twice daily for eightd weeks, and water quality parameters were maintained within known ranges suitable for juvenile Florida pompano.

For more detailed procedures on the experimental setup – including feed preparation and analysis; experimental design and feeding trial; growth performance, sample collection and analysis; tissue fatty acid analysis; and statistical analyses – refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

The juvenile Florida pompano accepted well all diets, no mortalities were observed, and overall growth performance was acceptable (Table 3 = Table 1). Weight gain (228 ± 20 percent, grand mean ± SE) and specific growth rate (2.2 ± 0.1 percent body weight/day) were unaffected by dietary treatment. Although no significant treatment effect was observed, animals receiving the FISH diet had, numerically, the greatest growth.

The growth performance of the fish was not affected by differences in fatty acid composition and dietary lipid source. Together with the lack of mortalities and any other indications of deficiency, this indicates the LC-PUFA content provided by the residual oil from fishmeal and the menhaden fish oil included in the diets was evidently adequate to meet the essential fatty acid requirements of Florida pompano juveniles.

Feed intake varied among dietary treatments. However, the range of values observed was relatively small (3.09 to 3.65 percent body weight/day) and the only significant differences observed were in some but not all comparisons between the MUFA SOY, C18 PUFA SOY, and PALM treatments (lowest feed intakes) and the FISH and SFA SOY treatments (highest feed intakes).

For FCR, a significant treatment effect was also documented, but the range also was relatively narrow (1.33 to 1.61) and the only significant difference was between the PALM (lowest FCR) and SFA SOY (highest FCR) treatments. Fish also exhibited a narrow range of hepatosomatic index (HSI) values (1.1 to 1.5), and only the POULTRY treatment (lowest hepatosomatic index, HSI, the liver weight as a percentage of the whole-body weight) and MUFA SOY treatment (highest HSI) differed significantly.

Rombenso, Florida pompano, Table 1

| Parameter | FISH | SFA SOY | MUFA SOY | C18 PUFA SOY | PALM | POULTRY | PSE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial weight (g) | 43.5 | 43.1 | 43.4 | 43.6 | 43.5 | 43.5 | 0.4 | 0.906 |

| Final weight (g) | 149.9 | 137.9 | 143.3 | 142.7 | 142.5 | 138.1 | 7.7 | 0.672 |

| Weight gain (%) | 245 | 220 | 230 | 227 | 227 | 218 | 18 | 0.709 |

| FCR | 1.48ab | 1.61ab | 1.41ab | 1.42ab | 1.33b | 1.49 | 0.04 | 0.012 |

| Specific growth rate (% body weight/day) | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.772 |

| Feed intake (% body weight/day) | 3.60ab | 3.65ab | 3.30bc | 3.31bc | 3.09c | 3.35abc | 0.1 | 0.001 |

| HSI | 1.4ab | 1.3ab | 1.5a | 1.2ab | 1.3ab | 1.1b | 0.1 | 0.041 |

Tissue fatty acid profiles were significantly influenced by dietary treatments and generally mirrored dietary fatty acid composition. Overall, fillets of fish fed the reduced fish oil diets had lower levels of omega-3 fatty acids and LC-PUFAs, and higher levels of the fatty acids that were abundant in the alternative lipids compared to those of fish fed the FISH diet.

Fillets of fish fed the SFA SOY diet had higher levels of SFAs, especially 16:0, vs. other dietary treatments. Fillets of fish fed the MUFA SOY diet had significantly higher levels of MUFAs, especially 18:1 omega-9, vs. fillets of fish fed the other diets. Fillets of fish fed the C18 PUFA SOY diet had higher levels of omega-6 and C18 PUFAs, especially 18:2 omega-6, vs. fillets of fish fed the other diets.

Fillets of fish fed the PALM and POULTRY diets – while not as enriched as fillets from the C18 PUFA SOY and MUFA SOY treatments, also had higher levels of omega-6 fatty acids, MUFAs and C18 PUFAs. We observed these trends, although to a lesser extent, in eye and liver tissues but not in brain tissue; the latter being comparatively resistant to diet-induced compositional change.

The distortion in tissue fatty acid profile was highest among fish fed the MUFA SOY and C18 PUFA SOY diets, least evident among fish fed the SFA SOY diet, and intermediary among fish fed the POULTRY and PALM diets. Even though the SFA SOY diet differed the most from the FISH diet regarding fatty acid composition, it produced the lowest tissue profile modification. Fillet and liver total lipid content did not vary significantly among dietary treatments.

It is known that fish oil sparing with vegetable- or terrestrial animal-origin alternative oils is generally successful, as long as the essential fatty acids requirements are met. Our experimental formulas replaced 75 percent of fish oil with alternative lipids, currently a commonly used replacement rate in the aquafeed industry, probably because this level of sparing is considered safe and not expected to reduce the content of dietary LC-PUFA below required levels by most species.

In terms of their combined EPA + DHA content, all experimental diets tested met or exceeded the lower end of the requirement range, and sustained 100 percent survival and adequate good. While significant treatment effects were noted for feed intake, FCR and HSI, it is improbable these differences are a significant concern from a practical or biological perspective, and are most likely related to minor differences in feed digestibility or palatability than to an essential fatty acid deficiency.

Regarding their fatty acid profile, all tissues analyzed were affected by dietary treatments, and generally imitated dietary fatty acid composition, which is highly consistent with the pertinent literature on fish oil sparing. All experimental diets tested produced fillets with reduced levels of beneficial omega-3 fatty acids and LC-PUFAs vs. the FISH control group. None of the diets produced the same fillet levels of omega-3 fatty acids or omega-3:omega-6 fatty acid ratio as the FISH control feed.

Perspectives

All diets evaluated in our study were well-accepted by juvenile Florida pompano, with none of the alternative lipids associated with loss of efficiency or growth impairment. Although fish fed the experimental feeds exhibited some loss of health-promoting omega-3 LCPUFA, this effect was less evident in fish fed diets containing more SFAs.

It should be noted that the SFA SOY feed, based on a blend of menhaden fish oil and hydrogenated soybean oil, best maintained overall fatty acid profile best and produced fillet tissues that would provide an amount of EPA and DHA per portion more comparable to that of fish fed a diet containing exclusively fish oil. Therefore, we suggest that SFA-rich feeds may offer some strategic advantage to preserve the fillet fatty acid profile and associated nutritional value of farmed Florida pompano.

Our results are encouraging but were derived from a relatively short-term trial (eight weeks) with juvenile fish. Also, the feeds were prepared experimentally and were not commercially extruded. Therefore, additional studies under conditions more closely approximating commercial production of Florida pompano and using extruded feeds for longer trials to fish commercial size are recommended.

References available from first author.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Artur Nishioka Rombenso, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Nutrition and Physiology Laboratory, Institute of Oceanography

Autonomous University of Baja California

Km 107 Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada

Baja California, Mexico 22860 -

Jesse T. Trushenski, Ph.D.

Fish Pathologist Supervisor

Eagle Fish Health Laboratory

Idaho Department of Fish and Game

1800 Trout Road

Eagle, Idaho 83616 USA -

Michael H. Schwarz, Ph.D.

Director

Virginia Seafood Agricultural Research and Extension Center

Virginia Tech

Hampton, VA 23669 USA

Tagged With

Related Posts

Aquafeeds

Replacing fishmeal with DFB in pompano diets

A study evaluated the inclusion of bacterial, dried fermented biomass as a replacement for fishmeal in four practical diets for Florida pompano juveniles. There were no significant differences in final weight, survival, FCR or thermal-unit growth coefficient.

Aquafeeds

Aquaculture Exchange: Rick Barrows

After 14 years with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, Rick Barrows talks about the importance of finding ‘complete’ and commercially viable alternative sources of omega-3 fatty acids and continuing innovation in the aquafeed sector.

Aquafeeds

Is a fish oil-free cobia feed possible?

The availability of a cost-effective grow-out feed formulation is an ongoing bottleneck for the expansion of cobia production. Studies by the authors show that the development of an aquafeed with limited or no fish oil content is possible.

Aquafeeds

Considerations for alternative ingredients in aquafeeds

A key to expanding aquaculture is finding alternative sources of proteins and oils. Supplementing or replacing fish oil in aquaculture feeds with alternative lipid sources – oils seeds, microalgae, insects and others – appears possible as long as essential fatty acid (EFA) requirements are satisfied.