Industry working to overcome production, export issues, COVID-19

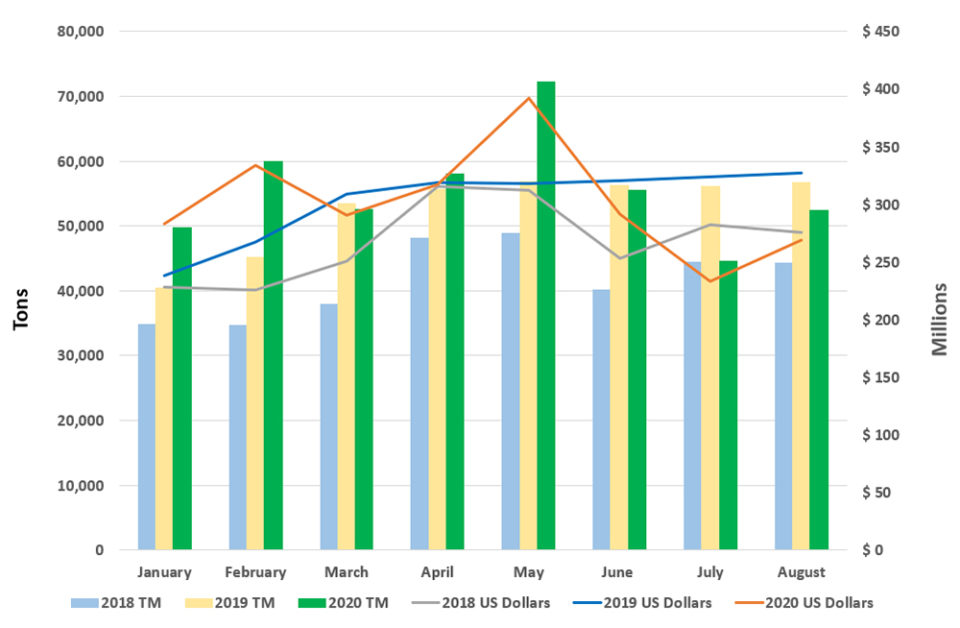

Without a doubt, 2020 has been a difficult year for everyone, and Ecuador’s shrimp industry is no exception. In addition to the drop in international prices – an ongoing trend since 2019 – the COVID-19 pandemic brought along numerous difficulties that have had to be faced and overcome, both from the public and private spheres. With the reduction in demand due to the confinement of the main shrimp markets, the industry has had to decelerate the positive trend of recent years. While the industry originally anticipated a 20 percent increase in exports for 2020, year-over-year, myriad challenges have forced a revision to that forecast of about 6 percent growth this year.

A challenging year

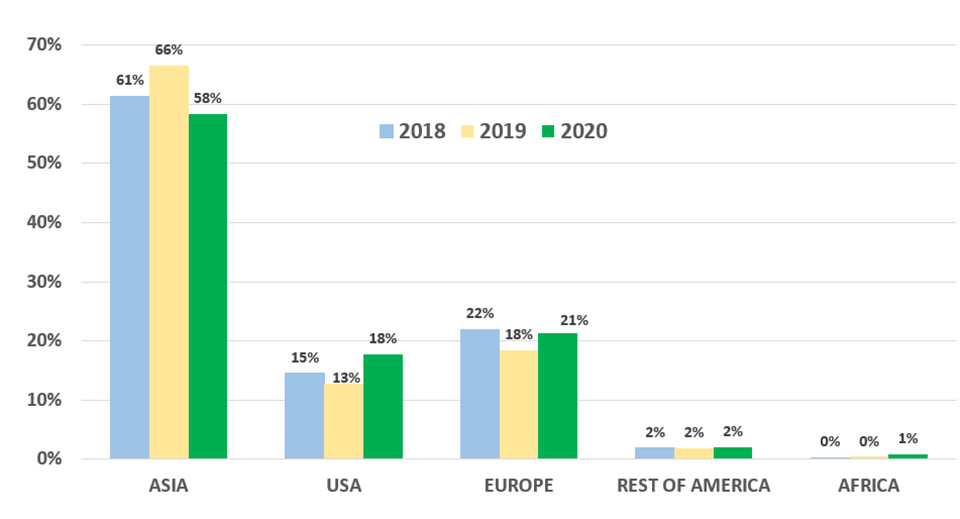

At the beginning of 2020, Ecuador’s shrimp industry was adapting its processes to comply with China’s import requirements, mainly so that every batch of shrimp exported to that market was free of White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV). The Subsecretariat of Quality and Safety (SCI) – the Ecuadorian competent authority – implemented PCR tests for each batch of shrimp destined for China, certifying for export only the pathogen-free batches. This requirement, which came into effect on December 9, 2019, meant a big change for the shrimp export sector, given that, overnight, 60 percent of its exports had to be tested. This new measure could be implemented thanks to the interconnected work between the public and private sectors, thus allowing it to satisfy the demands of its largest export market.

Added to this new effort was the havoc that the COVID-19 pandemic would bring. The first official report of a contagion in the country was reported on February 29. Immediately, the national government intensified actions to contain contagions, and shortly after, a state of exception was declared throughout the national territory for 60 days. The measures that were implemented included the suspension of working hours and academic activities; restriction of vehicle mobilization, associations and meetings; and a curfew for 15 hours a day, all of which were applied progressively as of March 16. Only personnel from the health sector, basic services, industry and food and export chains were allowed to mobilize.

Likewise, the Emergency Operations Committee (COE) assumed control of the situation and was in charge of ruling all the measures that would govern the Ecuadorian territory during the state of exception for the prevention of COVID-19 contagion among its citizens.

Effect of government actions

Regardless of whether the aquaculture sector and all its related activities could obtain authorization to maintain their operations, the restrictions decreed by the government represented great difficulties for companies in the sector to maintain their levels of operation during the mandatory quarantine period. These obstacles included the following:

- High level of absenteeism at work sites. A significant percentage of company personnel did not show up to work for fear of COVID-19 contagion. The government offered guarantees regarding labor stability to the workers in case of not showing up for their activities during the quarantine days, so that the workers did not feel forced to report to work if there was a possibility that they were sick.

- Transportation difficulties. The lack of authorized public transport made it difficult for personnel to move to and from the plants and farms. This was most felt in companies where a large percentage of workers come from rural areas. In all cases, it was necessary to hire private transportation services to transport personnel to work sites.

- Limited capacity for diagnostic tests for COVID-19. Due to the health emergency and the overload of health services, both public and private, suspected cases of contagion could not be confirmed in a timely manner. Therefore, as a preventive measure, those with symptoms were forced to isolate, reducing the available labor force.

- Increase in operating and logistics costs. The implementation of personal protection and biosafety equipment – as well as the payment of additional hours to workers who had to stay to cover absences and the hiring of private transportation services to move workers to and from the plants – represented additional expenses of up to 25 percent, depending on the location and size of the company.

Contingency measures to face the crisis

To maintain exports, various government services – including the issuing of certificates of origin, health certificates, laboratory analyses and customs declarations, among others – adopted virtual attention measures, as well as the digital delivery of certificates and permits to maintain the flow of operations.

At the sanitary level, the national authority issued a regulation aimed at strengthening the procedures, protocols and other complementary regulations for the prevention and control of risks related to the contagion of COVID-19 among fisheries and aquaculture workers, based on recommendations issued by the World Health Organization (WHO). These measures specifically include controls on the health status of personnel, the use of protective equipment, and cleaning and disinfection procedures. These provisions have been adopted by all the companies in the shrimp production chain, especially the processing plants, to safeguard the health of their personnel and ensure the health and safety of their product and are audited by the Undersecretariat of Quality and Safety to ensure effective compliance.

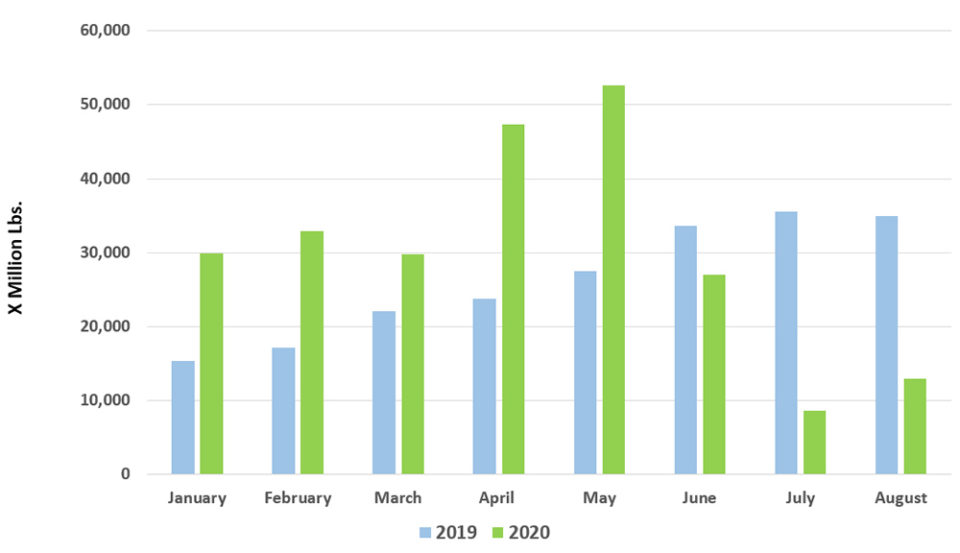

Regarding the operations of the shrimp companies, farm and hatchery stocking and harvesting schedules had to be rescheduled to avoid contagion and prevent collapses. Due to the difficulties already mentioned above, the processing plants did not have enough manpower to process shrimp at the regular rate of the industry, so the farms’ crops had to wait for a quota to deliver their product to processors. During the most critical days of the pandemic in the country, the plants operated at only 20 to 30 percent of capacity, and some closed temporarily for not having the minimum personnel needed for working shifts. This also delayed the new stockings, and thus the postlarvae demand from the hatcheries practically stopped for a few weeks.

A new blow to the industry

Despite the fact that at the beginning of July the city of Guayaquil showed a decrease in the positive cases of Covid-19 and that productive activity gradually had resumed, the industry had to deal with a new crisis when the General Administration of Customs (GACC) of the People’s Republic of China notified of the suspension to three Ecuadorian companies for the alleged detection of traces of COVID-19 on the surface of packaging (master boxes) and an interior wall in a container.

This was a heavy blow to Ecuadorian shrimp exports because the Chinese market represents 65 percent of total exports. The suspension generated uncertainty among all companies, which stopped their shipments to China and in many cases, had their containers returned to Ecuador. The accumulation of a large volume of shrimp in the domestic market further worsened the drop in shrimp prices at the local level, which is why shrimp from Ecuador came to be priced as the cheapest in international markets.

The Ecuadorian government – through the Embassy of Ecuador in China and the Ministry of Production, Foreign Trade, Investment and Fisheries (MPCEIP) – initiated dialogues with Chinese authorities in order to lift the suspensions. Due to the relevance of this industry crisis to the national economy, even the Ecuadorian president, Mr. Lenin Moreno, sent a communication to his Chinese counterpart to find a prompt solution to this situation. After several communications, the GACC requested to carry out virtual inspections in each of the sanctioned facilities to get information on the protocols and biosafety measures that were being implemented in these companies, and only those who satisfactorily complied with its requirements would be re-authorized to again export to China.

The National Chamber of Aquaculture (Cámara Nacional de Acuacultura, CNA) joined the work of the Undersecretariat of Quality and Safety (the national health authority) to support companies in their implementation of actions to reinforce current biosafety protocols and ensure that the risk was being controlled, prior to virtual audits. After the online inspections were completed, the temporary suspensions were lifted. However, two months of decreases in exports to China had already occurred, falling to 8,700 metric tons (MT) in July, a 70 percent contraction compared to the monthly average of the previous six months (36,000 MT).

This drop forced exporters to look for other markets to place their product, by increasing sales to the United States, followed by countries of the European Union. Despite the issues that both of these major markets have endured as a result of the pandemic, shrimp consumption in the United States and various European Union countries have responded favorably to consumption and as a result there has been an increase in the purchase of shrimp from Ecuador.

For the fourh quarter of 2020, exports are expected to show growth that will allow us to close the year at 6 percent above 2019. For this to happen, we expect that Chinese consumers will begin to regain confidence in Ecuadorian shrimp in the coming months, generating orders in preparation for the Chinese New Year that will be celebrated in February next year. In turn, in the United States, shrimp orders are also being generated for the Christmas holiday season, so an increase in demand there is also expected. Regarding the European market, high levels of purchasing are not expected because, despite entering the festive season, the winter season is also expected, which is not an incentive for the consumption of shrimp in that region.

Perspectives

Joint efforts between the public sector and industry have sustained the flow of exports and allowed the aquaculture sector to continue being one of the pillars of production, generating income and boosting the national economy.

Regardless, market prices have been the lowest in the last decade and an initial forecast for export growth of 20 percent in 2020 has since been revised to a 6 percent increase over 2019.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Diana Poveda

Head of International Trade Department

Cámara Nacional de Acuacultura

Guayaquil, Ecuador -

Yahira Piedrahita

Corresponding author

Executive Director

Cámara Nacional de Acuacultura

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Analysis, prevention of NHP in Panama, Ecuador and Peru shrimp farms

Based on histopathology and ultrastructure, the etiology of necrotizing hepatopancreatitis (NHP) in Pacific white shrimp was related to an intracellular bacterium.

Innovation & Investment

At GOAL, a peek at potential aquaculture futures

At the Global Aquaculture Alliance’s annual GOAL conference in Guyaquil, Ecuador, unfamiliar topics gave aquaculture industry leaders something to chew on.

Intelligence

GOAL 2018: A call for collaboration

From GOAL 2018: A global effort to share timely and accurate production data is what the aquaculture industry needs to thrive in today’s ever-changing marketplace.

Health & Welfare

AHPND is a chronic disease in Pacific white shrimp from Latin America

There is a new phase of infection for Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease on Latin American shrimp farms, a contrast to observations in Southeast Asia.