Aquaculture researchers: Scientific community and regulators need aligned definitions, terminology

How can anything be managed, if it cannot be defined?

For a nascent industry like offshore aquaculture – fish or shellfish farming outside of protected, near-shore conditions – clearly defining what it is, in concrete terms, could be crucial if it is to reach its potential as a solution to some of farmed seafood’s environmental impacts.

In a paper recently published in Frontiers in Marine Science, lead author Halley Froehlich, Ph.D., and her research team concluded that a deep dive into existing scientific literature on offshore aquaculture – or at least what the authors of those studies called “offshore aquaculture” – was first necessary in order to critically assess the impacts and benefits of moving fish farming operations “slightly farther and slightly deeper” out to sea.

“Offshore Aquaculture: I Know It When I See It,” sought to contextualize what the actual term means so that future analyses can be talking about the same things. Because if even scientists can’t get on the same page about what “offshore aquaculture” is supposed to be, then how can industry and governance?

“When I talk to people in fisheries, which is my background, the first question I always get is, ‘What is offshore aquaculture?’” said Froehlich, a researcher at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, University of California-Santa Barbara. “It kind of speaks to the reason why we selected the title that we did.”

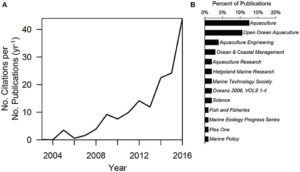

In a previous study that appeared in PLoS One, Froehlich, et al, discovered frequent negative perceptions in the media regarding aquaculture, particularly offshore. Those findings motivated the work on this new study, in which Froehlich and her team evaluated 104 peer-reviewed articles in major scientific journals (see Fig. 1) in which the term “offshore aquaculture” appeared. They then focused on the 70 studies that had a biological focus, or those that were linked to a specified animal or ecosystem. Of those, they found an overall lack of consistent reporting on even the most common location-focused metrics, limited impact-related studies and a narrow scope of the studies themselves.

Despite such loose connections, the researchers concluded that “depth, distance and currents” are the trifecta of factors for understanding offshore farming conditions. A farm operating in federal waters (at least 3 miles from shore, according to U.S. government regulations) is likely in depths of 30 meters or greater, where the environmental impacts of farming are diminished by swifter currents and fewer user conflicts.

You want the research that informs the policy that then informs the development – that’s the ideal chain of command.

“But we found that, on average, the distance for the farms we could find was 4.5 nautical miles from shore. And a majority of the referenced farms were much closer to shore, between 1 to 3 nautical miles, which is much closer than people may assume,” said Froehlich. “Same with depth – an average of 27 meters, well within the subtidal habitat. A lot of that has to do with money for the technology that can go out into deeper waters and withstand the conditions.”

Challenging conditions at sea and the related costs are a leading reason why offshore aquaculture activity worldwide is still quite limited. In the United States, it’s virtually non-existent, despite a management plan in place for the Gulf of Mexico, for instance.

For untapped areas like the Gulf, Froehlich believes aquaculture activity is also blocked by a chicken-and-egg kind of problem.

“You want the research that informs the policy that then informs the development – that’s the ideal chain of command. But with aquaculture, we’re finding that to actually get information, you need to have it happening in that environment. To get permits to put something in the water, it’s a lot of money and time,” she said. But without that farming activity, it’s “inherently difficult to do the science.”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

James Wright

Editorial Manager

Global Aquaculture Alliance

Portsmouth, NH, USA

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

Going deep on offshore aquaculture

Open-ocean aquaculture, the “new kid on the block” in the rapidly growing aquaculture industry, was examined at a California Academy of Sciences event. New contributor Twilight Greenaway reports.

Responsibility

Offshore aquaculture, a promising yet vexing venture

The challenges of farming fish in U.S. federal waters were the focus of a panel discussion at the SeaWeb Seafood Summit in Malta. Despite recent policy updates, U.S. aquaculture chiefs oversee an industry with high barriers for entry.

Innovation & Investment

Out of sight, not out of mind

Moving aquaculture offshore could spark a global production boost needed to meet growing demand for protein. Producers and investors, however, are wary of the challenges, cost and regulatory red tape. One patient U.S. entrepreneur, however, is undaunted.

Intelligence

‘Spatiotemporal patterns’ indicate improving perceptions of aquaculture

A study led by University of California Santa Barbara researchers has found that public sentiment toward aquaculture improves over time, a potentially important development with growing interest in offshore aquaculture.