Results show lower inclusion levels support better growth rates and water quality

The use of different microbial biomasses as sources of protein is receiving much attention from researchers looking for alternative sources of protein for aquafeeds. One of these sources is microbial flocs or bioflocs, widely used to culture various aquatic species because of their potential to enhance production through the provision of natural food in situ, in addition to other benefits. Biofloc can be collected from biofloc technology (BFT) systems as a high-protein, wet meal or as a dried meal after various drying processes. But novel methods to integrate biofloc meal into aquafeeds are needed to maximize nutrient recovery in farmed aquatic animals.

Biofloc meal is considered a high-quality source of protein and can be consumed and utilized by many herbivorous and omnivorous fish species. Tilapia is one of the potential fish species that can be cultured in freshwater and saline water and can tolerate a wide range of water salinity, and because of its omnivorous feeding habits, can use biofloc as a food source and its inclusion in diets can meet up to 50 percent of the protein requirements of the fish.

This article – adapted and summarized from the original publication (Binalshikh-Abubkr, T. and M.M. Hanafiah.2022. Effect of Supplementation of Dried Bioflocs Produced by Freeze-Drying and Oven-Drying Methods on Water Quality, Growth Performance and Proximate Composition of Red Hybrid Tilapia. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10(1), 61) – reports the results of research to investigate the efficiency of biofloc as a dietary supplement for red hybrid tilapia fingerlings reared in brackish water.

Study setup

This study investigated the effect of dried biofloc as a dietary supplement on growth, water quality and body composition of red hybrid tilapia fingerlings reared in brackish water (10 ppt).

Three indoor, tilapia biofloc system tanks at a commercial farm located in Sepang, Selangor, Malaysia, were used for biofloc collection. Biofloc samples were collected by net and transported to the laboratory at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Selangor, Malaysia.

The collected bioflocs were divided and one set was freeze-dried with a vacuum freeze-dryer for three days. The second set was dried in an oven at 40 degrees-C for three days. Both sets were then stored for diet preparation, proximate and experimental diets analysis.

Red hybrid tilapia fingerlings were purchased from a commercial fish farm located in Kuala Selangor, Malaysia. The fish were transported to the UKM laboratory (UKM), acclimated, and stocked into an experimental design of 10 glass tanks and individual life support systems for rearing. During the 57-day trial, data was collected on water quality, and fish growth performance and body composition.

The differently dried biofloc (freeze- and oven-dried) were evaluated at two inclusion levels (4 and 16 percent) and were compared to a control diet without biofloc in five experimental diets. The diets prepared were: T1, as a control diet, (100 percent commercial feed) without biofloc; T2 (4 percent freeze-dried biofloc), T3 (16 percent freeze-dried biofloc), T4 (4 percent oven-dried biofloc); and T5 (16 percent oven-dried biofloc). All ingredients were manually pelletized, dried and crushed, and the finished diets stored at 4 degrees-C until used.

For detailed information on the experimental design, biofloc collection, processing and diet preparation; fish husbandry; and data collection and analyses, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

Our results showed no significant differences between the means of the T2 and T4 treatments for all growth indicators. Similarly, no significant differences were found between the means of the T1 and T2 treatments for all growth indicators, except for the feed efficiency ratio (FER).

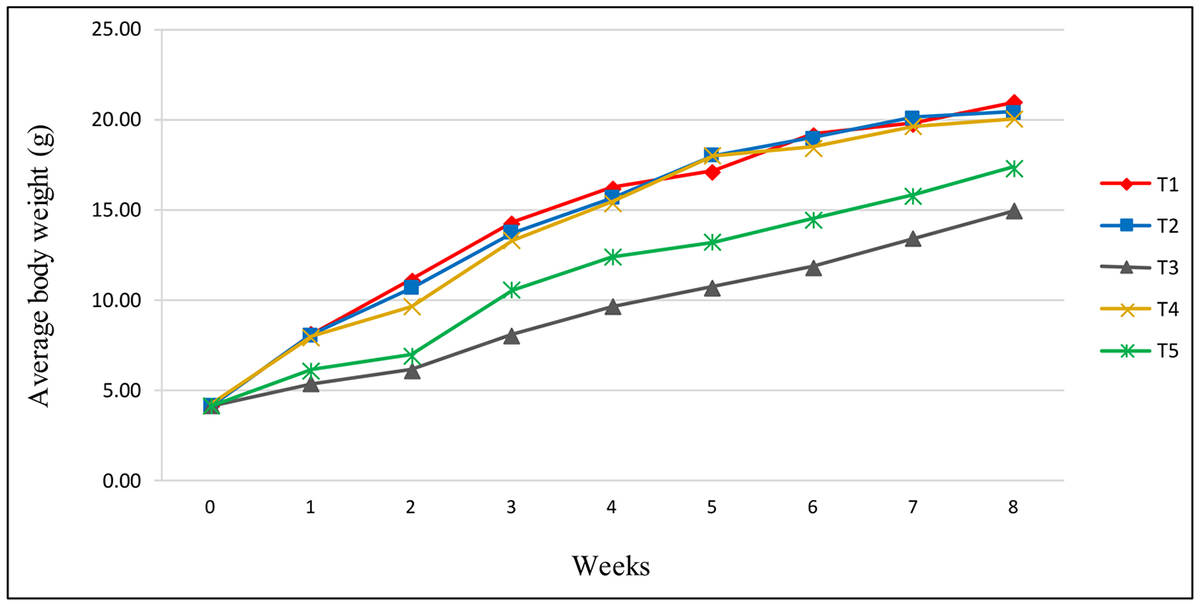

However, significant differences were found between the T1 and T4 treatments in terms of final biomass weights, total biomass gains, specific growth rate, feed intake per fish (FI), feed conversion ratio (FCR), and FER, but no significant differences in terms of initial weights, final weights, weight gains, initial biomass weights, protein efficiency ratio (PER) and survival rate between the same treatments. Also, significant differences were observed within the means of body weight for T3 and T5 treatments compared to the T1 treatment. And significant differences were observed between the means of final body weight for T3 and T5 treatments at the end of the experiment (Fig. 1).

The drying methods (freeze-drying and oven-drying) we used did not affect the growth performance of red hybrid tilapia fingerlings, while the inclusion levels of biofloc had a significant effect on growth in terms of final weights, weight gains, final biomass weights, total biomass gains, specific growth rates, feed intake, feed conversion ratios, feed efficiency ratios, protein efficiency ratios and survival rates.

The growth rate is considered the most effective parameter to examine the effect of any experimental factor on fish. In our study, the 4 percent inclusion level of freeze- and oven-dried bioflocs resulted in higher growth rates (final weight, weight gain, specific growth rate and survival), similar to those of the control diet, than diets with 16 percent inclusion levels of biofloc.

All water parameters in the experimental tanks were within the reported ranges for red hybrid tilapia culture. Regarding water quality, biofloc treatments T3 and T5 showed lower dissolved oxygen (DO) levels, but higher temperature compared to the control (T1) treatment). The control and T2 treatments showed no significant difference in pH values, with a slight decrease noticed in the latter. Meanwhile, the higher temperature in the biofloc treatments probably caused an increase in the water conductivity (EC) values. Overall, the decrease in DO and pH values, as well as the increase in EC values for the biofloc treatments, were probably due to the increase in water temperature in these treatments.

Phosphate concentrations in the water were within those reported by other researchers. However, the T3 and T5 treatments (fed 16 percent dried biofloc) had higher uneaten feed amounts and phosphate concentrations than the T1 (control), T2, and T4 treatments (fed 4 percent dried biofloc). Consequently, the increase in phosphate levels can be explained by the higher volumes of uneaten feed in those culture tanks.

Comparing biofloc, clear-water and hybrid RAS systems as shrimp nurseries

The higher biological oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) levels observed for the T3 and T4 treatments resulted in lower DO levels for the same treatments. Similar results have been reported by other researchers. The high levels of COD in our study might be due to the lower salinity used in the trial.

The proximate analyses of bioflocs showed different values for protein, lipid, and total nitrogen-free extraction contents between the two drying methods (freeze-drying and oven-drying). The dried biofloc produced by the freeze-drying method had higher protein content compared to the biofloc produced by the oven-drying method. Therefore, the protein content in biofloc can be influenced by the drying methods, and the freeze-drying method in our study positively affected the protein content in biofloc. In contrast, the crude lipid content was higher in dried biofloc produced by the oven-drying method.

When comparing the final fish body compositions for the five treatments in our study with the initial fish body composition, we found that fish fed 100 percent commercial feed (without biofloc) had better final product quality in terms of nutritional value, followed by fish fed the 4 percent oven-dried or freeze-dried biofloc diets. But all our values for final fish body composition were within the ranges reported in several previous studies.

Overall, the comparison of resulting data among the five experimental treatments (T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5) showed that the T1, T2 and T4 treatments (100 percent commercial feed, 4 percent freeze-dried biofloc diet and 4 percent oven-dried biofloc diet, respectively) had the best values for growth indicators, water quality parameters, and fish body composition. The T3 treatment (16 percent freeze-dried biofloc diet) had the lowest growth performance, water quality, and fish body composition, followed by the T5 treatment (16 percent oven-dried biofloc diet) in our study. Consequently, we believe dietary inclusion at 4 percent of the freeze-dried biofloc can help support efficient growth performance of red hybrid tilapia fingerlings, while the 4 percent oven-dried biofloc diet could be a low-cost and efficient alternative to better manage water quality parameters in tanks for the culture of red hybrid tilapia fingerlings.

Perspectives

Our results showed that experimental diets with a 4 percent inclusion level of freeze-dried and/or oven-dried biofloc have potential as a novel aquafeed ingredient, supporting higher and adequate growth rates (similar to the control diet, a 100 percent commercial feed) than diets with 16 percent inclusion levels of dried biofloc for red hybrid tilapia fingerlings reared at 10 ppt salinity.

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Dr. Tarq Binalshikh-Abubkr

Department of Earth Sciences and Environment, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 43600, Malaysia; and

Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Environmental Science and Marine Biology, Hadhramout University, Mukalla P.O. Box 50512, Yemen -

Dr. Marlia Mohd Hanafiah

Corresponding author

Department of Earth Sciences and Environment, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 43600, Malaysia; and

Centre for Tropical Climate Change System, Institute of Climate Change, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 43600, Malaysia

Tagged With

Related Posts

Intelligence

Advances in tilapia broodstock management

Female tilapia broodstock spawn asynchronously, producing only 2,000 eggs per clutch. Hatchery operators often run into low seed quantity and quality problems.

Intelligence

Considerations for tilapia farming in saltwater environments

Tilapias are farmed in a variety of production systems, but mostly in freshwater and low-salinity waters. But tilapias are an excellent candidate for aquaculture in brackish- and seawater because they can tolerate a wide range of water salinity.

Health & Welfare

Hybrid tilapia culture in an outdoor biofloc production system

This study in an outdoor biofloc technology production system evaluated impacts on fish production indices, common microbial off-flavors and water quality dynamics for hybrid tilapia.

Health & Welfare

Biofloc technology reduces common off-flavors in channel catfish

In studies that used biofloc systems to culture channel catfish, culture tanks were susceptible to episodes of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol and subsequent bioaccumulation of off-flavors in catfish flesh.