Why are fish populations in the Gulf of Maine in a state of flux? It’s the very composition of the oceans, say researchers.

The warning bells have sounded for years: Ocean warming is affecting the distribution, growth and reproduction cycles of fish, shellfish and other marine life around the world. The very composition of our oceans is changing, climate researchers say, bringing challenges for seafood harvesters, scientists and regulators alike.

Climate and ocean researchers also suggest that some marine species are more resilient and adaptive to the warming oceans than others. While the focus remains on species that are moving toward colder waters outside of their traditional range, there are examples of others that are absorbing change or adapting in other ways.

In the Gulf of Maine, for instance, populations of black sea bass and pollock appear to be on the upswing, according to a recent presentation at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI) in Portland, Maine. Herring counts have increased along the coastal waters of the Gulf of Maine, while the not-so-well-known red cod appears to be maintaining its traditional range. The news of herring’s rebound is good news for the state’s lobster industry, which uses herring as bait in traps.

“It’s not just all gloom and doom,” Graham Sherwood, a senior scientist at GMRI, told a crowd at the mid-November presentation, titled “Climate Resilience Potential in Gulf of Maine Fisheries.”

The waters of the northeast United States, and the Gulf of Maine in particular, are warming at a faster pace that virtually anywhere else in the world. It’s hard to ignore the impacts: Cod and other commercially valuable fish stocks are shifting northeast from their historical distribution ranges. Regulators a decade ago shut down the New England northern shrimp fishery after the population collapsed in the Gulf of Maine. Worries abound that the waters will also become too warm for lobster, the most valuable fishery in the Northeast and the lifeblood of Maine’s coastal fishing communities.

For the GMRI presentation, Sherwood and Zach Whitener, a senior research associate, only presented findings on finfish species – red cod, herring and Atlantic pollock and black sea bass.

Ongoing questions

GMRI research shows that red cod, a variation of the traditional olive-colored cod that is popular among consumers, have persisted in the kelp beds of Cashes Ledge, an underwater mountain range about 100 miles southeast of Portland. Sherwood’s research concludes that red cod live in warmer waters, while olive cod simply only visit warmer waters for short periods of time.

Herring stocks have declined across the Gulf of Maine since 2012, the first year that water temperatures began their upward climb in earnest, he said. But while the numbers have fallen sharply in offshore waters, herring have adapted by concentrating in colder waters close to shore, not moving to the northeast, he said.

The pollock population appears to be increasing, even while the waters have warmed to levels never seen before, Whitener said. During GMRI’s rod-and-reel jig surveys, researchers noticed color variations in juvenile pollock, with some fish being brown rather than their usual green color.

This idea of winners and losers is one way it’s framed, that some species will do well in a region and some species will not. That has been found in a number of systems around the world. But in the Northeast (United States), the magnitude of change is greater, and thus the magnitude of effect on our fisheries is greater.

This, Whitener said, raises the question of whether pollock is adapting to the warmer waters, with brown ones better suited to different temperature regimes.

“These are ongoing questions we’re excited about,” he said.

A recent study at William & Mary’s Batten School of Coastal & Marine Sciences suggests that the cold-water North Atlantic lobster may be more resilient to the effects of climate change than previously thought.

The study examined whether rising water temperatures and acidity levels had an impact on how lobsters groom their offspring and, subsequently, the survival rates of embryos. Experiments conducted at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science compared the behavior of two groups of lobsters. The control group was in water that matched the current conditions in the Gulf of Maine, and the experimental group was in water with temperatures and acidity levels that are predicted for the end of the century.

The study concluded that neither higher water temperature nor acidification caused significant changes in grooming behavior or impacted embryo survival, said Abigail Sisti, who is completing her Ph.D. at the Batten School and is the lead author on the study. “This is encouraging because it shows lobsters may be reproductively resilient to forecasted environmental changes,” she said in a statement.

Similar research around the world shows that other marine species are more resilient to rising water temperatures than previously understood. Even so, many more at risk.

Pine Island Redfish and MANG team up on coastal restoration initiative in Florida

Winners and losers

In the Northeast United States, where signs of change are strongly emerging, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 2016 released the first multispecies assessment of the vulnerability of fish and invertebrates to climate change in waters managed by the northeast region of NOAA. Of the 82 species that were examined, the study determined that 83 percent of them would either be hurt by or not affected by the warmer waters, while 17 percent would benefit.

Jon Hare, the lead author of the study and the director of NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Mass., said resilient species are those that can continue being productive under a broad range of environmental conditions.

For example, he said, species with a diverse diet are more resilient to change. If a fish’s favorite prey is herring, but it can also eat menhaden, then the flexibility of diet helps with resilience.

Species with broad habitat needs are also more prone to being resilient even when their environment is changing, he said. Fish that live among coral reefs are less resilient because they’re dependent on coral reefs; when coral reefs die off due to warming waters or increased ocean acidification, those fish have nowhere to go.

Hare often talks to other scientists around the world where warming waters are bringing about rapid change.

“This idea of winners and losers is one way it’s framed, that some species will do well in a region and some species will not,” Hare said in a phone interview. “That has been found in a number of systems around the world. But in the Northeast (United States), the magnitude of change is greater, and thus the magnitude of effect on our fisheries is greater.”

Hare said scientists will be redoing the vulnerability assessment of fish and invertebrates in the Northeast in the next couple of years. A similar review of the changing distribution of marine species along the Australian coast concluded that warming ocean temperatures were driving most species toward cooler waters in a poleward direction.

Like Sherwood, Hare said that the changing make-up of the ocean waters isn’t totally grim – but it does raise questions.

“For managers, for society and for all of us, how do we address the challenges for the species that aren’t going to do well?” Hare said. “And how do we find opportunities for species that are going to do well?”

Now that you've reached the end of the article ...

… please consider supporting GSA’s mission to advance responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. The Advocate aims to document the evolution of responsible seafood practices and share the expansive knowledge of our vast network of contributors.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Clarke Canfield

Clarke Canfield is a writer, editor and author who has worked for various newspapers, magazines and The Associated Press for more than 40 years. He has focused on commercial fisheries and marine-related issues for much of his career, and was once executive editor of National Fisherman and SeaFood Business magazines. He is also the author of a book about the New York Yankees. He lives in South Portland, Maine, with his wife.

Tagged With

Related Posts

Responsibility

A wider view: Conservation aquaculture anchors coral reef restoration

Half a billion people depend on coral reefs for food, income, coastal protection and more. The need to protect and restore their biodiversity is urgent.

Responsibility

All clams on deck: How restorative aquaculture can repair Florida estuaries

New legislation aims to tackle tough environmental issues in Florida estuaries by bolstering the number of clams and seagrass through restorative aquaculture.

Fisheries

Artificial intelligence algorithm from WCS is the first to correctly estimate fish stocks

Researchers created an artificial intelligence model that has successfully estimated fish stocks with 85 percent accuracy in trials.

Innovation & Investment

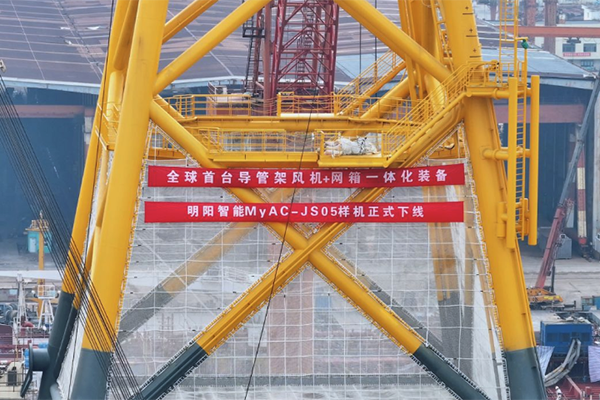

‘Possible, but still far away’: Offshore wind farms and aquaculture may one day go hand-in-hand

Initiatives to unite aquaculture and offshore wind farms are popping up globally but they face technical, cost and environmental challenges.

![Ad for [BSP]](https://www.globalseafood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/BSP_B2B_2025_1050x125.jpg)